Australian nut industry: From strength to strength

Consumer demand and prices for nuts have never been stronger, triggering an extraordinary expansion phase for the industry.

As the mighty Murray runs a banker just across the valley, Pip Crawford carefully kneels among her 22,000 newly grafted baby pistachio trees that fan into the distance across the terracotta red sandy soils near Robinvale.

It’s an ambitious 52-hectare expansion of the 270-hectare Sunraysia pistachio orchard where her family have pioneered farming and processing the popular small green snacking nut in Australia since 1984.

Now operations manager of Adelaide-based CMV Farms, which also grow 1100 hectares of almonds in South Australia and Victoria, Pip knows pistachios are a nut that does not suit everyone to farm.

Unlike almond trees that yield a commercial crop within three years of planting, the gnarled pistachio trees take seven to eight years before each tree bears a harvest of 30 kilograms of the delicate pinkish grape-like bunches of pistachio nuts every March.

“It’s an industry that has developed slowly; with it taking at least seven years before you get any returns, not many people want to jump on board because it requires patience and deep pockets,” says Pip, who trained first in viticulture and winemaking before joining the family business. “So there’s only a small circle of growers; out of necessity we’ve had to learn not just how to farm pistachio trees, but also how to grow out the rootstock in our own nursery, harvest and process the nuts and market them; we are always running little trials and trying new things.

“It’s why I love pistachios. There’s something about them as both a nut crop and an ancient tree that’s a bit mysterious; you think you’ve got them all sorted out and then they will go and do something a different – it certainly keeps it interesting.”

While the Crawford family and their processing partner, Chris Joyce, who owns Australia’s biggest pistachio orchard across the Murray river from Swan Hill at Kyalite, are currently the major industry players producing 60-70 per cent of the national crop, the pistachio industry is poised on the brink of massive expansion.

CMV Farms managing director David Crawford says rapid growth lies ahead for the industry as big new investors keen to be part of the stellar global “nut story” join the fray.

While Australian pistachio production currently sits at 3000 tonnes (kernel in shell) annually, with a farmgate value of $45 million, by 2030 it will have tripled in size to more than 10,000 tonnes a year.

CMV Farms already has plans to plant 250 more hectares of pistachios on new land it has just acquired adjacent to its current Robinvale farm. Other newcomers looking to move into pistachios include existing almond orchard investors Duxton and Hancock, and large vegetable and table grape growers, the Lamattina family and the Menegazzo family.

“But there’s plenty of room for such growth,” says David Crawford, who planted the first Australian-developed pistachio variety Sirora on his company’s Robinvale farm back in the early 1980s. “When we started out, all pistachios eaten in Australia were imported from Iran and more recently California; now locally we are producing 60 per cent of Australia’s needs (5000 tonnes).

“That demand, driven by both snacking habits and the increasing use of pistachio as a nut ingredient in the food industry, is already growing at 8 per cent a year, yet Australian consumption of pistachios per head is still only half of that of Americans.

“So we see potential for both the domestic market to grow and for exports of pistachios to develop.”

But pistachios are not the only nut crop in Australia facing rapid expansion and boom times. Figures from the Australian Nut Industry Council, representing Australia’s seven main tree nut crops – almonds, walnuts, macadamias, pistachios, hazelnuts, pecans and chestnuts – show the entire industry is riding a wave of extraordinary farming growth, rising consumer demand and relatively high commodity prices.

ANIC chief executive Cathy Beaton says the combined farmgate value of the nut industry this year sits at close to $1.2 billion, with 194,460 tonnes of nuts harvested from 89,450 hectares of tree nut farms. But by 2030, based on current and planned new plantings of nut orchards across Australia, and allowing for at least three to four years for trees to reach maturity, the value of the national nut crop is expected to nearly double to $2.1 billion.

Total nut production will exceed 318,000 tonnes on the back of $500 million of new investment every year being poured into new tree nut plantings for the past five years.

Almonds, macadamias, walnuts, pecans and chestnuts are already exported to more than 65 countries with export sales exceeding $800 million a year, a figure that will jump 75 per cent to $1.3 billion in the next four years.

Tree nuts already surprisingly account for a 40 per cent of Australia’s horticultural exports – almonds are the nation’s most valuable horticultural export commodity – with most Australian nuts attracting a premium price in export markets for their quality, supply reliability and food safety standards.

Farm productivity has also never been higher. Gross revenue per hectare for tree nut crops ranges from $20,000 to $30,000, with recent technology advances delivering water use savings and a high rate of return of $2000-$3000 for every megalitre of water applied to the trees.

These economic returns are 10 to 20 times higher than the return from traditional irrigated crops such as tomatoes or vegetables, bringing prosperity to the main nut growing regions of Australia along the Murray River in South Australia, Victoria and NSW, around Griffith and Narrandera on the Murrumbidgee River, and along the coastal fringe of NSW and up to Bundaberg in southern Queensland.

It’s a flourishing, but quiet, success built on what industry players and agri-investors call the phenomenal “nut story”.

Simply, nuts such as almonds, pistachios and walnuts are seen as one of the food groups the world will come to rely on in the next century for their basic nutrition.

Nuts are packed with plant-based protein and dietary fibre, heart-healthy fats, vitamins, minerals and antioxidants. They also neatly fit into every sort of diet of the future, whether it is regarded as a fad or a serious future food trend.

The industry promotes daily nut consumption – ideally 30 grams a day – as reducing heart disease, lowering the risk of type 2 diabetes and assisting with weight management.

Yet the ANIC says Australians are not eating enough nuts, with just 2 per cent consuming the health target of a handful of nuts a day. ANIC board member Jolyon Burnett says 30 grams of nuts per Australian is not such an ambitious consumption target, equating to eating either 20 almonds, 15 cashews, 20 hazelnuts, 15 macadamias or 30 pistachios.

“It’s an extraordinary growth story ahead, but the industry will also need to expand export opportunities to ensure the new orchards and production coming into maturity don’t result in an oversupply of nut, reduced prices and softer returns to growers,” Burnett says. “Pursuing opportunities in key new markets such as India, Europe and the Middle East with high growth potential is regarded as critical to the expansion into a $2.1 billion industry by 2030.”

Paul Thompson, the affable chief executive of Select Harvests, one of the world’s biggest almond growers and one of Australian agribusiness’s rare $1 billion ASX-listed companies, has his hands deep in compost.

Alongside his horticultural technical officer, Upul “Guna” Gunawardena, Thompson is checking progress of the innovative trials underway at Select Harvest’s major almond processing plant at Carina West, near Robinvale on the Murray River, where mountains of hull and shell “waste” collected with every almond harvest are being turned into valuable liquid fertiliser, compost and biofuel.

“We put a lot of effort, water and fertiliser into our farms to grow a tree that bears as much fruit as possible, just to make use of the 30 per cent that is the seed (nut kernel) inside,” Thompson says. “The hull and shell wrapped around it – that’s 60,000 tonnes of biomass growth a year – we have treated as waste and sold as low-cost cattle feed; but with water availability in the Murray Darling Basin now a limiting factor, we have to add value to all our biomass as well, not just the nut, if we are to keep growing as a business.”

It’s all part of his four-year strategy to move Select Harvests from solely being a producer, processor and exporter of nearly 30,000 tonnes of bulk almonds annually, to a company that adds value to as many of the almond nuts it sells as possible in the form of new foods, almond milk and confectionery.

The idea is that “can we get more bang for the environment, and more returns for us”, says Thompson, by using all the waste woody hull, shells and orchard prunings to turn into liquid fertiliser and compost for Select Harvests’ own trees, to continue to fuel its organic waste biomass boiler and power co-generator and, potentially, to sell to other farmers as the price of fertiliser escalates worldwide.

“It’s potentially a really positive carbon story; instead of releasing carbon via feeding cattle with our shells and hulls we are recycling all the organic waste into ash, compost and liquid fertiliser, which then will replace much of the artificial fertiliser we now use in our orchards and improve our soil structure, soil carbon and water retention,” Thompson says. “It’s a win for the environment and a win for us.”

Thompson is justifiably proud of how he has taken Select Harvests in the past decade from being a company struggling to survive in the ruins of the Managed Investment Scheme failures which had funded many early almond plantings along the Murray, to today become Australia’s second-biggest almond producer (after Olam).

Almonds are now the nation’s most valuable horticultural export commodity, with almond kernel exports having exploded from 21,000 tonnes a decade ago to 76,700 tonnes in 2020-21 valued at $A545 million. Domestic consumption has also doubled to 30,000 tonnes in the same period.

About a quarter of the nation’s current 114,500 tonnes of total annual almond production is grown on Select Harvests’ extensive farms. It exports 80 per cent of its almond crop via global traders or direct to multinational food manufacturers such as Mondelez (Cadbury), Chobani and Unilever, and the rest is sold to Coles, Woolworths and Aldi.

“We are not going to see that growth rate again because the water is not available,” says Thompson, who is a strong supporter of the Almond Board’s call for a moratorium on the issuing of any new water licenses in the Murray Darling Basin that would support new greenfield almond plantings. (In the past decade, almond farms have expanded from 27,000 hectares to nearly 50,000 hectares.)

“We use about 14 megalitres of water a hectare to irrigate our trees and have used all the latest technology to increase our water-use efficiency by more than 20 per cent. We don’t waste water, but the focus is on getting more nuts and more biomass for every megalitre rather than limiting it.”

Another massive corporate player in the Australia nut industry – this time dominating in walnut and pecan production, as well as being a new macadamia player – is the new conglomerate of Stahmann Webster.

It is owned by the all-pervasive Canadian Public Sector Pension fund, which now holds more than $3 billion of agricultural assets in Australia.

In both walnuts and pecans, Stahmann Webster now grows more than 85 per cent of the national crop, with walnuts processed at its Leeton factory, and pecans at its Toowoomba facility. Its total nut crop is valued at about $100 million, a commanding 10 per cent of all Australia’s nut production.

“We like to own and manage our farms and processing facilities and right through the supply chain: we are a gate-to-plate company,” chief executive Ross Burling says.

“Domestically consumption is on fire and we are on a big growth curve with all four nuts we farm; but globally, Covid has dampened prices by 10-15 per cent and supply chains are clogged; I think we are in a catch up period now before demand takes off again.”

ANIC figures predict that by 2025 national walnut production will have increased by 71 per cent and pecans by 175 per cent. Hazelnuts are also set for a massive 21-fold increase in production by 2025.

In the heart of one of the nut industry’s fastest-growing farming regions live Andrew and Zoe Lewis, progressive young macadamia growers in the thriving irrigated district of Bundaberg-Childers on Queensland’s Capricorn Coast.

In the past 11 years since the couple, who previously worked in finance and construction, bought their first Bundaberg farm, they have toiled tirelessly farming cane and peanuts, while starting their own macadamia orchard from seed.

Last year the Lewises, who have three young children, finished the final plantings in the five-year conversion of their 150-hectare cane farm west of Bundaberg to all macadamias, with the 30 per cent of trees planted in 2016 and 2017 now yielding a commercial first harvest of 80 tonnes of macadamias.

Andrew says they were attracted to the region by the fertile sandy loam soils, the secure and cheap irrigation water from the Burnett River and Paradise Dam, and its semi tropical rainfall which provides half of each tree’s water needs.

“There’s a lot of trees going in; there’s now more than 10,000 hectares of macadamias planted around Bundaberg, it’s just been huge in the past five years,” says Andrew, who admits to being relieved his planting phase is complete.

“Here you get economies of scale. And the fact it’s a high yielding and high return crop gives you the luxury of spending more time and money on soil and plant health, trying to increase the soil carbon content and organic matter around your trees, and spreading compost because it increases your water holding capacity and pays you make with more maccas.”

The Lewis family is typical of the huge rush of farmers, investors and corporate agribusiness companies into Bundaberg in the past decade, many converting struggling low margin sugarcane properties into high-value macadamias.

It’s a huge turnaround for the native Australian nut which for many years suffered from being something of a fad crop.

But now Australian-grown macadamias are on the ascendancy. Jolyon Burnett, chief executive of the Australian Macadamia Society, says the arrival of bright young farmers like the Andrew and Zoe Lewis, as well as the big money commitment from corporate farmers has made the Bundaberg region the centre of macadamia growing in Australia.

The area of macadamia production is increasing by 5000 hectares a year, with $150 million invested annually.

The Bundaberg-based Steinhardt family, traditionally big tomato growers, have just invested $35 million in a new Macadamias Australia processing plant and tourism centre, while the Arrow investment company recently bought a grazing property near Maclean, NSW, and have planted a new 800-hectare orchard.

Other major corporate players include listed Rural Funds Management, which plans to invest $500 million over the next decade into 5000 hectares of macadamias; Belgian Finasucre, which bought 1000 hectares of established macadamias from Hancock Agriculture for $59 million; and Canadian pension fund PSP Investments, which owns a macadamia cracking plant in Toowoomba and is expanding its macadamia farms.

“Macadamias are the second-most important nut grown in Australia after almonds, with production worth $350 million a year and likely to double by 2030,” says Burnett, pointing out that only 1 per cent of nuts eaten globally are macadamias, leaving plenty of room for export growth in new markets.

A NUTTY WORLD

As the world turns away from meat and dairy products to plant protein, high energy healthy foods and quick fast snacking products, it is not surprising that nuts tick all the right boxes.

With a protein content of 8-23 per cent in common nuts such as pistachios, almonds and cashews, the nibbling on raw or roasted nuts, using more nuts in cooking – think nut burgers – or eating foods with nut ingredients such as macadamia ice-cream, Nutella hazelnut spread or pecan protein bars has become a simple way to deliver maximum energy and nutrition to the body without having to eat massive volumes of food.

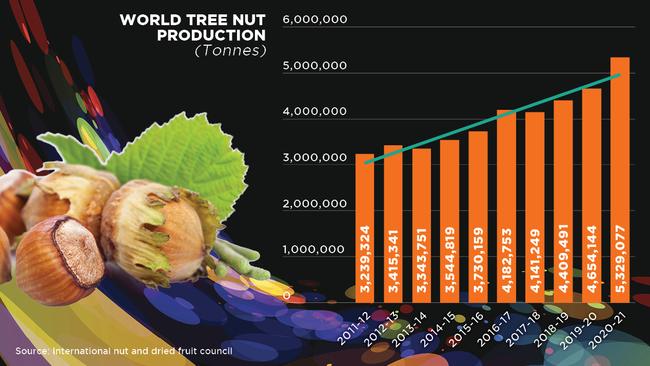

Nut demand worldwide has more than doubled in the past decade, with predictions such rapid growth will only continue.

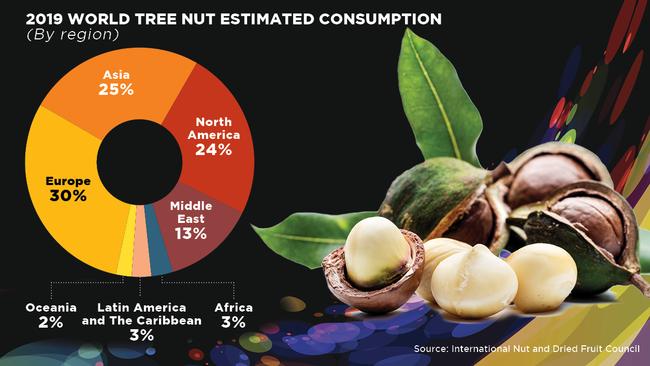

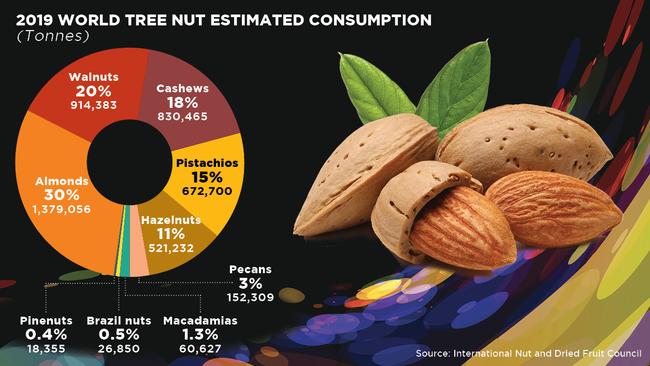

In 2019, world tree nut consumption exceeded 4.58 million tonnes, according to the International Nut and Dried Fruit Council. The global supply of nuts is now valued $US42 billion, a steep rise of 36 per cent since 10 years earlier.

A third of all global consumption is almonds, while 20 per cent is walnuts. The next most popular tree nuts are cashews (18 per cent), pistachios (15 per cent) and hazelnuts (11 per cent). Macadamias account for just 1 per cent of global tree nut consumption.

Other figures confirm the nut craze. For example, in the US, every person on average ate 1.73kg of nuts in 2010; by last year consumption had jumped to 2.5kg per capita.

Nut exports volumes and values from Australia have followed suit.

Last year 121,663 tonnes of nuts were exported, with tree nut industry exports now valued at nearly $1 billion. Almonds accounted for 55 per cent of exports, alone valued at $545.3 million last year.

In Australia too, consumers are searching for nuts with a new vigour. Demand for nuts, both for eating as a snack and as a food ingredient in everything from muesli and chocolate bars to nut-based flours, soaps and milks has soared.

For example, in 2010, total domestic almond sales were 15,631 tonnes. Last year, local consumption had doubled to 31,600 tonnes.

The almond industry likes to point to its ubiquitous presence in at least eight different aisles of the supermarkets. There are fresh almond packs for snacking in the fruit section, almond meal for baking in the flour aisles, almond milk in the refrigerators, almond ice-cream in the freezers, almond soap and hand creams in the cosmetics aisles, almond protein bars and snack packs in the health food and vegetarian department, almond flakes in the nut and cooking section and sweet coated almond confectionery in the chocolate aisles.

This boom has been the driving force behind a huge increase in global nut crop production, which has now reached 5.3 million tonnes. Production has grown 65 per cent in the past 10 years and a phenomenal 15 per cent in the past year alone.

In Australia, tree nut production now has a farmgate value of $1.13 billion. Seven types of nuts are grown in Australia – almonds, walnuts, macadamias, pistachios, hazelnuts, pecans and chestnuts – totalling 172,000 tonnes annually.

Plantings have also grown rapidly to 85,500 hectares, with many trees yet to reach maturity and full production.

The dominant almond industry tells the full story. In 2000 there was just 3500 hectares of almond orchards in Australia. By last year, 58,500 hectares of land had been planted with more than 17 million almond trees, and 33 per cent had not yet reached mature production.

Jolyon Burnett, who sits on the Australian Nut Industry Council, describes nuts as a “booming food category”.

He says that across the world and in all types of nuts, demand is now outstripping supply; a situation that shows no sign of abating despite increased investment and plantings in key nut producing countries, such as Australia.

“We’re seeing increases in prices paid for all nuts – although Covid has interrupted those price rises a little – and there is no reason to fear that more plantings will eventually swamp demand or cause an oversupply and a price drop,” Burnett says.

“It’s an incredible industry to be involved with and it’s hard to say anything bad about nuts from either a health or sustainability perspective; the future is looking pretty good.”