Avian influenza outbreak: Columbia bans US beef imports

Columbia is the first country to ban beef imports from certain parts of the United States as the outbreak of avian influenza in dairy cattle continues to grow.

Columbia is the first country to ban beef imports from certain parts of the United States as the outbreak of avian influenza in dairy cattle continues to grow.

Late last week, Columbia said it would no longer accept beef imports from states where AI has been found in dairy cattle, including Kansas, Ohio and Texas.

And while total US beef exports to Columbia were just $40 million of the $10 billion last year, the beef industry is already raising concerns over the move.

A spokesman from the US Meat Export Fedration said the ban had “no scientific basis”. “Colombia is the only country that has officially restricted imports of US beef and the USMEF is encouraged that the vast majority of our trading partners are following the science on this matter,” the organisation said in a statement which branded the move “unworkable and misguided”.

The move by Columbia comes as US authorities have ordered all dairy cattle must test negative to highly pathogenic avian influenza, prior to being moved interstate, in a bid to stop the rapid spread of the virus.

The US Department of Agriculture’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service issued the order last night, which will come into effect on Monday.

USDA has identified viral spread between cows within the same herd, from cows to poultry, between dairies associated with cattle movements, and cows without clinical signs that have tested positive.

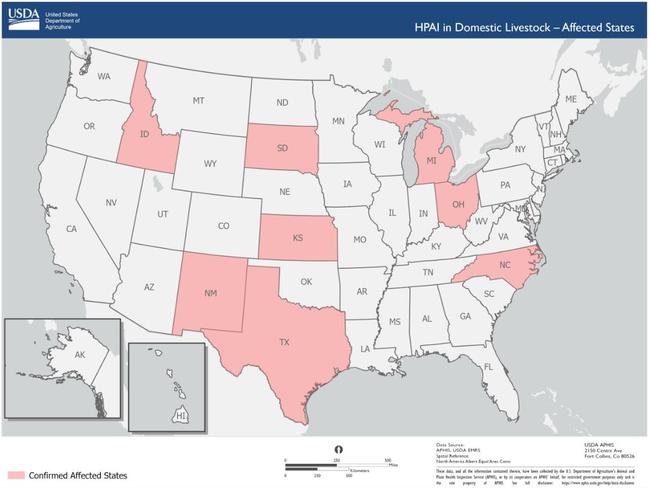

The outbreak of avian influenza has rapidly spread through US dairy herds, from just seven outbreaks across three states last month to 33 herds across eight states this week.

The USDA has also confirmed eight poultry farms in five states – Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, New Mexico and Texas) – have also been infected with the same HPAI H5N1virus genotype detected in dairy cattle.

Symptoms of infection in dairy cows include decreased milk production, reduced appetite, thickened and discoloured (yellow) milk, lethargy, fever and dehydration.

However the USDA has recently detected the virus in the lung tissue of an asymptomatic cull dairy cow, which originated from an affected herd. The cow did not enter the food chain.

“HPAI has already been recognised as a threat by USDA, and the interstate movement of animals infected with HPAI is already prohibited. See 9 C.F.R. 71.3(b),” the APHIS order states.

“However, the detection of this new distinct HPAI H5N1 virus genotype in dairy cattle poses a new animal disease risk for dairy cattle – as well as an additional disease risk to domestic poultry farms – since this genotype can infect both cattle and poultry.”

HPAI is a threat to the poultry industry, animal health, human health, trade, and the economy worldwide.

The initial dairy herd infections have been attributed to contact between birds carrying the avian flu and cows.

But just how the virus is now being transmitted from cow to cow remains a mystery, with the journal Science reporting US Department of Agriculture veterinarians have postulated the virus may be spread in the dairy, during milking or droplets on workers hands or gloves.

During a virtual meeting last week USDA National Veterinary Services Laboratory officer Suelee Robbe Austerman told World Organisation for Animal Health officials “right now, we don’t have evidence that the virus is actively replicating within the body of the cow other than the udder”.

The USDA has confirmed the H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b of the virus contains the mutation that has allowed it to adapt to infect mammals.

However Australian avian veterinary specialist Peter Scott, who advises the federal government on its AI Ausvet plan response, said there was still “significant uncertainty on the spread and transmission of the virus in cattle”.

“It’s all under investigation,” Mr Scott said.

The USDA has advised producers to move animals with clinical signs of infection to a dedicated hospital or sick pen, which does not share confined air space, fence lines, feed or water with other animals.

USDA is also advising beef cattle producers on the symptoms of AI and the need to isolate animals, but has stated “at this time, USDA will not be issuing federal quarantine orders”.

Both the US Food and Drug Administration and USDA have stated they believe commercial milk supplies are safe, because of both the pasteurization process and the required diversion or destruction of milk from sick cows.