Kristina Hermanson on Nuveen Natural Capital’s $2.2b investment strategy in Australia

The world’s biggest farmland investor, Nuveen Natural Capital, owns a whopping $2.2b of Aussie farmland. Kristina Hermanson oversees all of it.

Kristina Hermanson has a view from the top.

As she sits down at a boardroom table on the 33rd floor of an office building high above Sydney’s CBD, taking in the spectacle of the world-famous harbour and its iconic bridge and opera house, the former American Mid-West farm girl who once dreamt of being an astronaut takes time out to reflect.

It’s a rare week at home for the globetrotting 48-year-old, who has quickly risen through the ranks to be considered among the most powerful people in Australian agriculture. As head of Asia Pacific and Africa at Nuveen Natural Capital – the world’s biggest investor in farmland – Hermanson oversees investment and strategy for a diverse portfolio of more than 65 properties and agribusinesses occupying 350,000 hectares of prime Australian farmland valued at a whopping $2.2 billion.

Backed by the New York-based Fortune 100 financial company Teachers Insurance and Annuity Association of America, and with supporting capital from 50 other global investors, Nuveen Natural Capital and its predecessor Westchester Group has been a constant on the Australian farming landscape for more than 15 years.

It is considered, along with Canada’s PSP Investments and Macquarie Agriculture, one of the “Big Three” institutional investors in Aussie ag, with strategic cropping and horticultural assets spread across NSW, Western Australia, Queensland and Victoria. Together the trio has more than $10 billion worth of farmland assets under management locally.

Chat with Hermanson for long enough and you get the sense that for all her time spent in airport lounges, on long-haul flights crisscrossing the globe or in boardrooms meeting with clients or potential investors, she’s most at ease away from the bright lights: out in the bush talking shop with her management team, sharing ideas with fellow farmers, getting dust on her boots.

“I was speaking with a friend today, and I think in agriculture in general – even if you’re in Australian agriculture – you’ve got to get out to the paddock, you’ve got to be on the farm or with the farmer, talking to people, you have to be at a field days. That interaction is really important,” a down-to-earth Hermanson says while also acknowledging she is time poor in a role where “there is no (such thing as a) normal week” just “blocks of time”.

SMALL START IN BLANCHARDVILLE, WISCONSIN

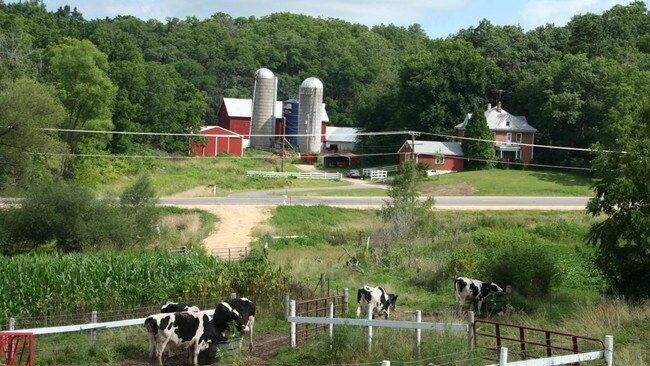

Farming is firmly entrenched in Hermanson’s DNA. She grew up on a fifth-generation dairy farm outside Blanchardville, Wisconsin – a “little-bitty town” with a population of 824 southwest of Madison.

Her forebears arrived in the region from Norway in the late 1800s and the family’s 110-hectare property, which Hermanson and her siblings still own a stake in, was home to a dairy herd of 40-50 head and “truly diversified”.

“I’m very thankful for growing up on a farm, learning the value of hard work and really appreciating nature,” she points out. “We had woodlands, fishing ponds, some productive farmland up on the top, lots of pastureland and some not-so-great farmland. It was literally one of those farming mosaics.”

Hermanson immersed herself in farming during her youth, growing up with the 4-H youth organisation and Future Farmers of America, which provided “such great opportunities” for up-and-coming agriculture enthusiasts.

Her mother’s hope that she “never married a dairy farmer” made a strong impression, and upon finishing school she followed the bright lights to Madison and enrolled at the University of Wisconsin where she studied mechanical engineering with an astronautics option, keeping open her path to the stars. Upon completing her studies, however, she focused her attention closer to planet Earth, moving to Switzerland where she worked on gas turbines for power generation for six years.

Passionate about bringing experts “to talk together, work together and think through the strategy and how we keep developing forward”, Hermanson then completed an MBA through the University of California. It was during her studies she had a “sliding door moment” where she met the then-chief executive of multinational food processing and commodities trading company Archer-Daniels-Midland, which prompted her to turn down a job offer with The Boston Consulting Group to instead run ADM’s refined oils business across Europe.

Australia beckoned in 2013 when she moved to lead the integration of ADM’s $3 billion proposed takeover of GrainCorp. It would prove a baptism of fire: Hermanson arrived at the start of one week and by the end of it the deal was controversially rejected, with then-Treasurer Joe Hockey bowing under pressure from local grain growers and the National Party, declaring it contrary to the national interest.

Despite this setback Hermanson remained in Sydney, working with ADM as a director of business development and strategy across South-East Asia. She then spent two years as director of growth and collaboration with Coca Cola Amatil before returning to her agriculture roots with agricultural sciences company FMC as managing director of its $US300 million Australia, New Zealand and ASEAN business employing 700 people in eight countries.

PATH TO AUSTRALIA

Hermanson joined Nuveen Natural Capital in January this year. She says she was attracted to the newly created role of Africa and APAC boss due to its “growth opportunities and looking at the next frontier of investment”.

“I thought it was a great opportunity to move away from quarter-to-quarter reporting, which doesn’t work very well in agriculture, to a much longer-term view,” says Hermanson, who is married to an Australian with whom she shares an eight-year-old daughter and two step children. “I’ve always believed that institutional investment, large organisations, can make a really big difference in the world.”

Nuveen Natural Capital traces its roots back to the Westchester Group, which was founded in 1986, in Champaign, Illinois, using proprietary capital provided by TIAA. It took its first step outside the US with investments in Australia in 2007 and now has $US12.4 billion invested across 600 farmland and timberland assets in 10 countries globally. Its farmland business is valued at $US10.6 billion.

Unsurprisingly the bulk of Nuveen’s capital is tied up close to home in the US, where it has a footprint of 304,000 hectares valued at $US6.6 billion. It has also invested heavily in Brazil (420,800 hectares worth $US2.9 billion), Australia (348,000 hectares worth $US1.5 billion) and Poland (46,500 hectares worth $US540 million). Additionally it has farmland and timberland assets in Romania, Panama, Chile, Uruguay and New Zealand.

Most of the investments are in row crops, accounting for 44 per cent of the total value, followed by timber (16 per cent), sugarcane and winegrapes (14 per cent each) and horticulture (12 per cent).

In farmland, the business works on a strategy of both leasing land out to farmers under a tenant model as well as operated businesses. Its theory is that leasing delivers more consistent revenue in rent with minimal volatility, while custom operations are exposed to higher returns but greater volatility.

NUVEEN’S GLOBAL PORTFOLIO

Australia is an important cog in the Nuveen Capital wheel. Hermanson says initially, in Westchester’s hunt for scale, Australia presented an opportunity from a row-crop perspective, albeit different from the business’ proven corn and soybean model in the Mid West. Australia’s regulatory framework, supporting innovation, also made it an attractive destination for capital.

The bulk of Nuveen’s row cropping business is now in NSW and Western Australia, with additional assets in Queensland and Victoria. More recently the business has expanded into permanent crops such as almonds and macadamias, and viticulture, an investment area Hermanson expects will grow.

She says row crops gave investors the opportunity for strong capital growth of underlying land while with permanent crops the business invested in “biological assets”.

Of Nuveen’s 66 Australian farms, 60 are operated under the tenant model. The assets operated in collaboration with crop managers include the 430-hectare ME Farms macadamia operation near Bundaberg in Queensland, for which Nuveen paid a reported $71 million last October, and the Huddersfield almond orchard near Darlington Point in NSW.

Hermanson says Nuveen’s Australian investment strategy, overseen by an asset management team at Wagga Wagga and staff in Western Australia, northern NSW and Queensland, follows a tried-and-true recipe with geography, accessibility and opportunity as key ingredients.

“(With investments) you are looking for value, you are looking for scale – depending on what it offers, possibly a transformation, possibly an area that has some conversion capability across the farm, maybe more irrigation potential to be able to build in and diversify,” she says. “Certainly in the horticulture area there has been a lot of conversion, whether it be sugarcane to macadamias or cotton to almonds – so bringing farms to the highest value, and the highest and best use is really important.”

NATURAL CAPITAL FOCUS

Westchester Group was rebadged Nuveen Natural Capital in February last year, part of a company-wide push to cater for changing investor expectations. It followed research that found more than two thirds of institutional investors planned to increase their spend on natural resource investments as they sought to limit climate-related risk-exposure and align portfolios to a sustainable economy.

“Investors were looking already at that time – and that’s only accelerating – more and more at solutions that look across regenerative farming, sustainable timberland and ecological restoration,” Hermanson says.

“While natural capital gets a bit of a sexy appeal, the reality is it’s always been natural capital, whether it was my home farm in Wisconsin or some of the first farms (Westchester) bought in 2007. The difference now is a more deliberate focus on the resilience that it brings on the farm.”

Hermanson says, put simply, natural capital can be characterised as “the foundation to drive the global economy”.

“It’s all the things we think about: the land, air, water, crops, but probably more importantly it’s the things that we might take for granted or don’t really see or don’t have a simple value attached to: pollination, climate regulation, air quality regulation, soil health and soil erosion regulation,” she says, citing estimates that $900 billion of Australia’s gross domestic product is linked to a healthy environment and pointing to a three-gap challenge in the preservation of biodiversity, climate and productive farmland.

On farm productivity, Hermanson says with the world’s population forecast to grow to nine billion by 2050, 60 per cent more calories, 100 per cent more protein and 200 per cent more timber are required to sustain it. “If we don’t have that, maybe nothing else matters,” she says. “Getting the productivity to continue increasing by focusing on new technology, having a great track record (especially here in Australia) and keeping that up are key – and not taking precious hectares out of highly productive farmland.”

On the biodiversity front, she says there is “a real sense of urgency around the (development of a) nature repair market that incentivises farmers and institutional investors to take a serious look at biodiversity investments” while on climate “with corporations making strong commitments for both climate and nature – some are really on the front foot, others are fast followers – we are on a pathway but again we have to continue to maintain the (momentum) and integrity.”

INVESTMENT AND SUSTAINABILITY STRATEGY

Putting its money where its mouth is, Nuveen has completed a natural capital register across each of its 65-plus properties, calculating its value “to Nuveen, to the tenant, to society” in pilot programs around the world.

“When you measure (natural capital) and you think about the cost to maintain it and then potential future ecosystem service return then you can really start to manage it,” she says.

“We are now looking at farmland a bit differently … still looking for the productive farmland in driving the returns but looking at resilience for that farm around biodiversity, possible carbon projects and food and fibre production, but also resilience in the farming practices to maintain soil health and water retention. That is a conversation we are having with a lot of our investors today.”

Hermanson says a recent biodiversity mapping project across all Nuveen properties showed the potential of harvesting natural capital returns.

The Nuveen team zeroed in on a 130-hectare area of one farm in Western Australia that boasted a number of habitats in between cropping. She says the land was not the greatest in terms of yields and provided an opportunity to be rezoned as a trial project.

It was registered with the Clean Energy Regulator – “going through the nuts and bolts of how that is done … it is not all simple the first time around” – and then planted with 15 different species of native trees.

“They are starting to grow. So we now have that experience, we know what the governance process will be. What does that generate? Over the 25-year period that’s about 13,000 tonnes of carbon – if you put that into dollar terms it is at least $350,000 in revenue over 25 years. It is not a huge amount but it is a small piece of a large productive farm. Small pieces can add up to a large sum.

“If you put it in terms of number of cars – it’s similar to taking 112 cars off the road every year.”

The strategy also raises the question of what to do with carbon credits once they are generated. Hermanson says while “some investors may have interest in monetising those credits, (others) may have interest in taking them and retiring them against their own commitments”.

Looking forward Hermanson says so much excites her about the future of agriculture, including getting the balance between productive farmland, nature and climate right.

“It is an extreme challenge and the challenge of our time,” she says. “Being right in the forefront of that as Nuveen being the thought-leader in bringing new strategies on the ground is fantastic.”

NEW FRONTIER: AFRICA

For Kristina Hermanson, witnessing the winds of change blow across Africa’s farming landscape is one of the most fascinating aspects of her job.

In the 10 months since taking on the role as head of APAC and Africa with Nuveen Natural Capital, Sydney-based Hermanson has completed a number of trips to the world’s second-largest and second most-populist continent – home to more than 1.4 billion people. There, while she sees challenges, she also sees plenty of opportunity for Africa as “the next frontier” of agriculture.

“With the biodiversity, climate and productivity gaps the world faces, it is really important as the largest global farmland investor to look at the next frontier,” Hermanson says.

“If you look at maps out to 2050 and 2100 of GDP growth, population growth and water development over time there is a very interesting area that emerges in sub-Sahara Africa.

“There are also some real red zones,” she points out. “But it is an area that absolutely warrants a serious evaluation.

“We see a lot of public-sector investment coming into that region – there has been some great projects, particularly for yield increases and market linkages of smallholder farmers, but very little private sector and institutional investment, so we are exploring that.”

Hermanson says such a move requires significant due diligence “to really think through all the risks and then think through the mitigations”, adding there are numerous opportunities to provide food security for the continent based on 2100 projections.

She says any foray into the African market by Nuveen would mirror its entrance in the Australian market in 2007 where it “grew slowly and deliberately over time, and really aimed to add value to the land but also to investors and the community”.

Hermanson says South East Asia “in a similar sense” is also a frontier market, requiring work to increase scale “in harmony” with smallholding farmers.

“We will focus first on Africa, evaluate, make the right decision at the right time, and then (look at) South East Asia. There is certainly opportunity there whether that is timberland or ecological restoration as well.”