Woodstock Flour: Courtney Young and Ian Congdon on their boutique flour-milling

Jaw-dropping grain prices and a boutique flour-milling trend are opening doors for Australian growers to be price makers, not takers.

Technically speaking, their work is a daily grind.

But ask Ian Congdon and Courtney Young which of their everyday farming tasks are most rewarding and they are quick to say milling their family’s wheat and rye into stoneground flour vies for top spot.

The young farmers own and operate two micro mills on their 40-hectare property at Rutherglen, in Victoria’s North East, grinding one tonne of flour a week from grains bought from, and grown on, Ian’s parents’ 810-hectare organic cropping property, Woodstock, at Berrigan NSW.

Their brand, Woodstock Flour, is named after that slice of Riverina land, and the success of their small business has helped the couple achieve farmland ownership themselves.

It has also allowed them to pay Ian’s parents a fair price – decoupled from the global market – for some of their grain.

Launched seven years ago – when the couple was still living and working on the Congdons’ broadacre farm – the business has gone from strength to strength, selling flour directly to bakeries, independent shops and consumers online.

“There is definitely lots of interest in what we are doing and that is why we are continuing to grow,” Young says. “It has happened quite organically.”

Congdon and Young are part of a boutique milling trend that is sweeping the globe, allowing nimble growers who are savvy at marketing to carve out a niche in the premium flour market. In Victoria, that group includes Wimmera grain growers Stephen and Tanya Walter, of Burrum Biodynamics, who mill their own grain into flour on farm. And Jason Cotter of Tuerong Farm on the Mornington Peninsula, who takes his grains all the way to the customer’s plate with an on-farm mill and bakery.

Both here and overseas, an increasing number of local consumers are willing to pay a premium price for high-quality flours with provenance because they are concerned about food security, the environmental effects of their purchasing decisions and the nutritional value of their produce.

In Australia, the trend is adding an interesting new chapter to the nation’s milling story.

From a high of 500 operating across Australia in the 1870s, the number of flour mills has steadily decreased. About 30 businesses remain today with three of those – Allied Pinnacle, Mauri ANZ (a division of Great Western Foods) and Manildra Group – dominating the market. Now, tiny mills are popping up across the nation again, many in or near cropping communities and driven or supplied by farmers who are reclaiming price-making power over some of their harvest.

“We’re paying $750 a tonne for the certified organic grain that Ian’s parents grow,” Young says.

“In a drought year that was below the organic price. But this year it should be above the price for their grain. We are trying to work out what works best for Ian’s family and for us. It is different in terms of cash flow because we purchase the grain on a monthly basis.

“That has been something for Ian’s parents to build into their business … but it works out quite well compared to the organic price they would get on the whole.”

The price also works out well for Congdon and Young, with the average wholesale price for their flour sitting at $3.60 a kilogram – or $3600 a tonne. After six years in business, income from the venture has allowed them to plan a profitable future on their new 40-hectare Rutherglen property, where they have started a wheat crop of their own and added sheep for lamb production, selling boxed meat to the local community.

“Having the flour mill is definitely going to make this block of land feasible,” Young says. “I don’t think we could justify the cost of land if we weren’t getting a really good premium for what we produce here. We can see a future in farming because of it.

“That is something that we try to communicate to a lot of young farmers who are interested in what we are doing. If land ownership is part of your farming plan you need to be really nailing the marketing side of things. You can’t just be producing commodities on a small scale.”

Demand for local flour became turbocharged across Australia during the pandemic.

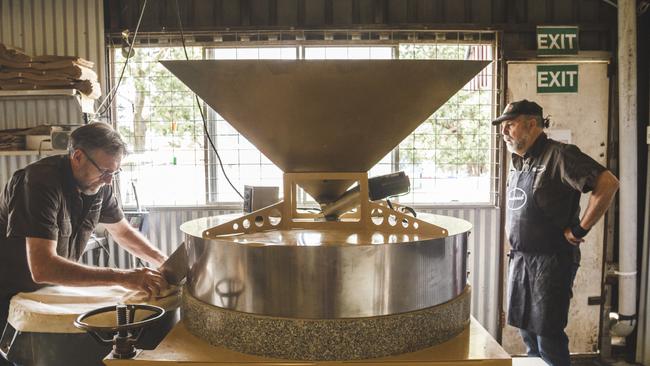

So too did logistics and operational challenges for small millers, highlighting the lack of mill manufacturers and maintenance support in Australia. Congdon and Young launched their business with a single custom-made New American stone mill imported from Vermont in the US.

“It is fantastic, but it kind of sucks in terms of troubleshooting and maintenance when the person who made it is on the other side of the world,” Young says. Searching for a locally made alternative, there weren’t a lot of options. So, Congdon and his brother, Hamish, decided to build their own using granite stones sourced from the Riverina.

Painstaking work went into the finished product, which is their second mill. It also opened another business opportunity when requests for the brothers to replicate the mill started to pour in from growers and local food groups.

They were commissioned by Queensland food distribution group Food Connect, run by Robert and Emma-Kate Pekin, and that completed mill is now housed in the not-for-profit group’s collaborative “shed” in Brisbane. Soon to be operating as the Salisbury Mill, it will be used to grind local grains to supply bakeries across southeast Queensland with ethically sourced, nutritionally dense stoneground flour.

Robert Pekin founded Food Connect 18 years ago, on a mission to connect farmers directly to the people who buy and consume their food. Starting with vegie producers and dairy farmers, Food Connect’s network of farmer suppliers soon expanded to croppers, with the group also supporting value-adding businesses that work in partnership with growers to create short supply chains.

“We are trying to come up with another model that completely reinvents how food should be priced and valued,” Pekin says.

The Salisbury Mill venture will buy grain from at least seven local growers, setting prices based on farmers’ individual circumstances.

“The true cost methodology is the reverse of the current food system,” Pekin says. “Farmers tells us what the cost are, we then add all that together and say for us to make a profit we need to mill one tonne of flour a week and sell it at this price.

“It is not at all open to the vagaries of the market.”

Pekin knows how farming businesses can be decimated when producers lose control over setting their own prices. He was the fourth generation at the helm of his family’s dairy herd at Colac, in southwest Victoria, when the disparity between his costs and his farmgate price led to him losing the farm in 1998. The loss nearly killed him.

“I was pretty busted up,” Pekin says. “I had no connection with where my milk went, who ate it nor the price I was getting for it. It took me a long time to lick my wounds and stand upright. Over time I wiped away the tears and I said if I’m going to be of any use, I need to be on the solution side of things.”

In an ideal world, he envisions demand for Salisbury Mill flour being so strong that local buyers could support “200-300 mini mills dotted across southeast Australia” in the future.

Meanwhile in Victoria, the market is fairly well balanced, Congdon and Young say.

“I think Victoria has the highest concentration of small-scale millers in Australia,” Young says. “We get lots of interest from Queensland and parts of NSW … that is where a lot of the action seems to be happening.”

FIGHTING FOR A FAIR PRICE

On-farm milling is just one strategy giving croppers more control over the prices they receive for their commodities, but it is not the only avenue for growers to extract more value.

Quambatook farmer and Grain Growers Ltd chair Brett Hosking says multiple marketing strategies including forward trading, fixed contracts and extended selling periods help growers command the best prices for their harvests.

But, he insists, there are still big questions about why grain prices in Australia have not hit the same highs during the past year’s volatility as the peaks seen in the international market.

Hence, he is leading the industry charge calling for the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission to investigate the big disparity and inject more transparency into the industry.

“During the election campaign both parties, Coalition and Labor, committed to further looking into the potential for a market inquiry and efficiency within the grain market. Post-election that has continued with both sides (of politics),” Hosking says.

In particular he hopes for more visibility of grains stocks held in Australia – “where they’re held , who owns them, what the quality looks like”.

“If a trader isn’t sure of the quantity, quality and location of particular types of grain, can they really compete as hard or seek out market export opportunities for that grain without the certainty of being able to accumulate that grain when required?”

He says an ACCC inquiry would unpack everything from transport costs and infrastructure to supply-chain bottlenecks, and show how improvements could be made.

“It is an industry that was deregulated 14 years ago,” he says. “The question growers are asking is … when we made such a massive structural change to the way our industry operated, did we get the settings exactly right. Most commonsense people would say we probably didn’t.

“We have canola selling in excess of $900 a tonne, wheat prices are in excess of $400 a tonne, it is very hard to think that they wouldn’t find 50 cents or $1 a tonne that could be added.

“If you translate that across a 60-million tonne grain crop each year, it is hard to imagine there isn’t $30-$60 million worth of value not making its way back to those rural communities where the grain is produced at the moment.”