‘Pulses are underrated’: Crop pumps life into grain industry

Once considered exotic, pulse crops are now pumping new life into the grains industry. AgJournal magazine takes an in-depth look at the crop capturing the attention of Australian grain growers.

WEST Victorian grain grower and professional agronomist Ben Cordes knows better than most what it is like to live and farm in the “Pulse capital of Australia” on the Wimmera’s fertile grey soil plains.

The Longerenong College-educated farmer, 32, has called the small Wimmera town of Rupanyup home all his life and proudly labels himself as a fifth-generation son of “Rup”, as locals fondly call their rural base. Employed as an agronomist to advise local farmers on their crops, it is a job that has allowed Cordes to observe first-hand the quiet revolution in the growing of legumes and pulses such as chickpeas, lentils and faba beans across the Wimmera.

Twenty years ago, legumes were primarily grown on many farms as a “break” crop, sown once every four years in a rotation cycle between mainstream wheat and barley – and increasingly canola for oil – that dominated the Wimmera.

They were widely regarded as somewhat inferior newcomer plants, but tolerated because they helped control weeds in between the all-important cereals and oilseeds, reducing the need for herbicides.

In addition, new-arrival crops such as chickpeas – using Australian-suited varieties bred locally from those grown in dry areas of the Middle East – offered a better alternative to leaving an empty paddock “resting”, or fallow, with the broad-leaved crop that is part of the pea and bean family providing paddock cover from the hot sun and helping retain soil moisture for the next cereal crop. As a bonus, pulses naturally add vital nitrogen back into the Wimmera’s depleted soils, saving farmers some of the cost of expensive fertilisers.

“Pulses weren’t sexy or important crops in their own right; they were sort of always secondary to wheat and barley,” Cordes says. “But all that has changed; now there are a lot of farmers growing pulses as their primary crop because the prices they command are generally high, the gross margin profits they offer farmers are often better than cereals, they store well so can be sold when prices are best, and demand for plant proteins such as lentils, faba beans, split peas and chickpeas from consumers is taking off worldwide.”

MORE AGJOURNAL

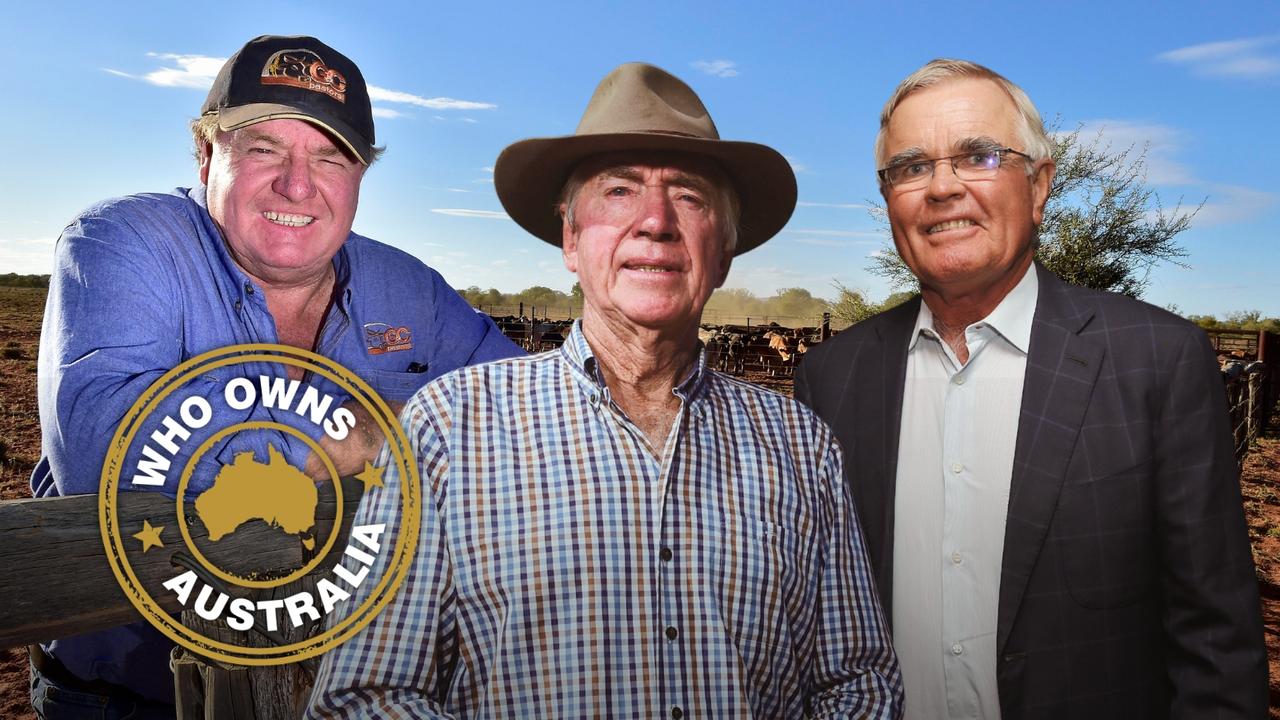

TOP FOREIGN INVESTORS IN AUSSIE FARMS

BEHIND AUSTRALIA’S DAIRY-INDUSTRY CRISIS

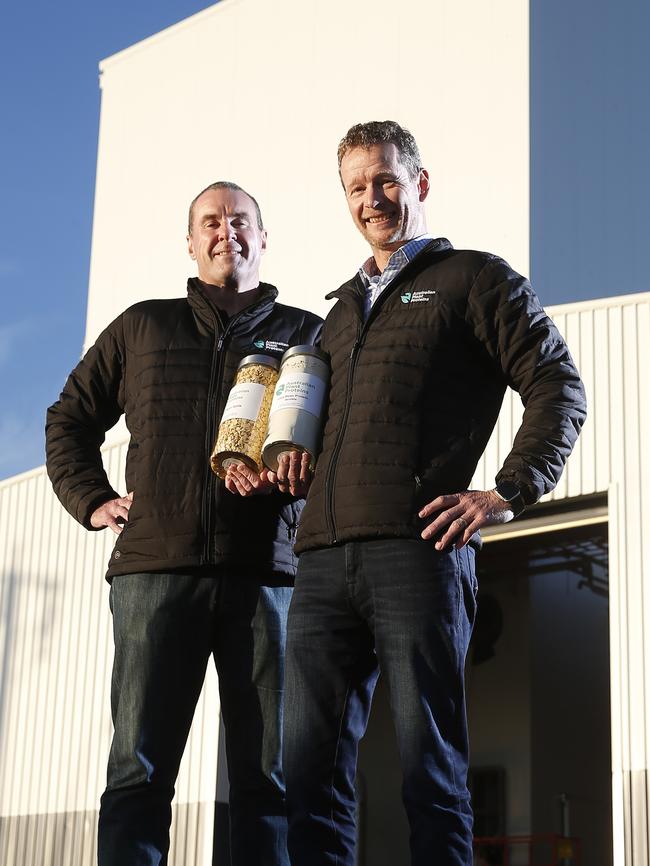

A key development for the Wimmera pulse industry this year is the opening of a hi-tech $21 million faba bean processing plant at Horsham, owned by private company Australian Plant Proteins. It uses a unique protein isolation, fractionation and filtration technology perfected at CSIRO’s Food Innovation Centre at Werribee to process the prosaic beans into ultra-high-value concentrated protein powder, creating the first significant pulse food processing and manufacturing factory in Australia.

The APP plant will, in its first phase, buy 12,000 tonnes of faba beans grown locally across the Wimmera, to process into 2500 tonnes of protein powder.

The powder will be sold to multinational food companies as an ingredient, producing everything from protein health bars and protein sports shakes to non-meat burgers, “boar-free” bacon, alternative protein “milks” and foods that use plant proteins instead of eggs in baking and confectionary products.

By October 2021, the plan is for a second $50 million factory that will buy 25,000 tonnes of raw faba beans annually to produce 6000 tonnes of 85 per cent pure protein powder. Lentils will also be used in this second stage.

A greenfield “super site” using a staggering 120,000 tonnes of faba beans annually to produce 30,000 tonnes of powder – which is better tasting, less coloured and more flexible in its uses than soybean powder – is also in the wings. That alone would consume almost 30 per cent of Australia’s expected faba bean harvest this year.

APP founder and director Brendan McKeegan says because APP is producing a “new” food product, he doesn’t think the significance or potential impact of the plant has yet sunk in with local farmers.

“I think pulses are underrated by many farmers; this is a really valuable supply chain we are creating here in Horsham in the heartland of Australia’s pulse industry, yet I don’t think a lot of farmers have grasped that yet,” McKeegan says.

“In five years’ time, on the back of what we are doing here, I suspect that it will be pulses like faba beans and lentils that have become the primary crop in the Wimmera and wheat and barley will be the less valuable ‘filler’ crops.”

In processing the raw faba beans (better known as broad beans) into protein powder, about four tonnes of crop with an average protein content of 26 per cent is transformed into one tonne of powder with a protein content of 85-90 per cent.

This process, of which APP owns the exclusive worldwide intellectual property rights, turns faba beans, which farmers sell for an average $700 a tonne, into an almost-pure plant protein powder that food manufacturers – both Australian and overseas – are eager and even desperate to currently buy for $10,000-$12,000 a tonne.

The hull and fibre of the bean left over in the processing can be sold as either stock feed or, potentially much more profitably, allowed to ferment and degrade to produce methane gas and renewable energy to power the APP processing plant, giving it a carbon-neutral footprint and adding to the product’s “green” credentials.

Critical, too, to the location of the APP factory in Horsham is that more than 40 per cent of lentils and faba beans harvested in Australia are produced in the Wimmera.

It is no coincidence either that APP co-founder and director Phil McFarlane is the son of a grain grower from Brim, 75km north of Horsham.

“This is such an exciting, emerging industry,” McFarlane says, “from the fantastic world demand we are seeing for our plant protein powder, the opportunities could become huge. Even we at APP are amazed at the level of interest from really big players in the global supply chain saying we need you to run harder, faster and bigger, as quickly as you can.

“Our customers are not just buying high-quality protein powder; they want the full-on Australian farmgate story, about how the soils here are low in toxins, how sustainable production is and the low water footprint and food miles of our crops.”

While the first pulses – think of crops with edible seeds in pods varying from peanuts and soybeans to peas, lentils, chickpeas and lupins – grown in Australia were navy (haricot) beans at Kingaroy, Queensland, to keep locally stationed US troops during World War II fed with familiar baked beans, it has taken the industry a long time to accelerate and boom.

Lupins were pioneered in Western Australia in the 1960s to improve its trace-element-deficient soils, and the first mung beans and chickpeas were grown in southern Queensland in the 1970s. But all the seeds (pulses) produced were sold primarily as low-value livestock feed; even by 1990, less than one million tonnes of pulse crops were harvested each year across Australia.

Yet, 30 years later, 8-10 per cent of Australia’s cropping land is now sown annually to pulse crops. In the pulse capital of the Wimmera, flourishing crops of red and green lentils, faba beans, kabuli chickpeas and yellow peas cover almost a quarter of farm paddocks.

This year, in what is looming as a bumper cropping year across most of South Australia, Victoria and NSW, ABARES predicts the 1.73 million hectares of Australia’s cropping plains sown to pulses will conservatively yield a harvest of more than 2.36 million tonnes. Worth $1.5 billion-$2 billion annually to the nation’s economy, the bulk of the pulse crop is destined for high-value export markets and food manufacturers.

Bangladesh is now the main buyer of 47 per cent of Australia’s chickpea crop worth $359 million annually (up from a 17 per cent share in 2017), Pakistan buys 26 per cent (up from 16 per cent) and the United Arab Emirates has emerged as a third key player. New markets have also been found in Nepal, the UK and Canada.

As farmers with trucks filled with stored chickpeas and lentils from last year’s harvest line up in Rupanyup’s main street to deliver their valuable loads, popular Wimmera Grains Company manager Sudath Pathirana says his pulse-dependent export business is “positively booming”.

“We shipped out 66,000 tonnes in the 2019-20 financial year from Rupanyup, about two-thirds of it “nipper” red lentils bound for Sri Lanka and Bangladesh,” says Sri Lankan-born Pathirana.

“Chickpea exports have dropped 19 per cent since India imposed tariffs (in 2017) and the market collapsed, but in some ways we haven’t noticed; beans are growing in strength and Rupanyup is really lentil country anyway, it’s a staple crop here now and the bulk of our exports,” he says.

The majority of farmers here are young, well educated and super informed.

Pathirana says the boom in the pulse industry – lentils sold for as much as $930 a tonne in March and April – has also led to a noticeable change in both the type of farmers in the Rupanyup area and their attitudes in the past few years.

“The dynamics are really different here now; the majority of farmers here are young, well educated and super informed,” he says.

“They are not traditional wheat and barley farmers and they don’t follow the old farming system of just selling and delivering their crop to the silo in town as soon as they harvest it – they all have significant on-farm storage capacity, watch the price signals daily, won’t sell their crop unless the price is right and know exactly what is happening in the market price-wise.

“Most significantly, many now see pulses as their main source of income, and not just a by-product of cereal rotations and nitrogen addition.”

At Burrum, where their father, David, pioneered pulse growing and great grandfather started farming nearly 100 years ago, brother and sister Dominique, 28, and Campbell Matthews, 21, represent the new face of Australia’s pulse industry.

Campbell, home during the coronavirus pandemic from Melbourne University where he is studying business and commerce, says more than 400 hectares of the farm’s 1400 hectares of crops is this year planted to pulses – most of it chickpeas, red lentils and the coveted Le Puy French green lentils, which the family has an exclusive licence to grow.

For Dominique, the pulses break the monotony of traditional cropping. “They’re good to grow; I find pulses more interesting than wheat or barley because you are not monoculture farming and there are so many uses for them, that you feel like you are part of the new trend of helping people eat healthier,” she says.

“We also supply the green lentils and some of the chickpeas we grow to my aunt Jenny (Matthews), who then packages them for retail use and adds value too (under her Wimmera Grain Store brand). I love that we are growing crops that we know will end up as chickpea flour, lightly salted chickpeas, lentil straw snacks or even lentil burgers grown here by us and processed and sold by my aunt.”

Also intent on adding value and promoting Rup’s “A Town with Pulse campaign” is Claire Morgan, a vivacious cafe owner. She uses chickpea flour processed by Jenny Matthews – some of it grown on Claire and husband David Morgan’s own farm – to cook and sell naturally gluten-free chickpea flour brownies on the main street of Rupanyup. So popular have her brownies become that a disability service in Horsham now packs her chickpea flour brownie mix for Claire to sell online to loyal gluten-free customers across Australia. “I love showcasing what we grow so well in Rup and the Wimmera; it’s about the great community here that is all committed to working together and sharing our story,” Morgan says.

On his family farm near Rupanyup, Ben Cordes is already planning to start growing faba beans next year – possibly under contract – to meet a demand he can only see increasing from the Australian Plant Protein factory in Horsham.

A key factor is that the new APP factory does not care about the physical appearance of the beans – only their protein content – removing the fear many growers have that late spring frost will damage or shrivel their faba bean crops and relegate them from export human-consumption quality to lower priced stockfeed grade.

“I think it’s a terrific investment for the area. We are so fortunate to have APP setting up in the heart of the Wimmera, which is Australia’s pulse capital,” says Cordes, standing in one of his young fast-growing lentil paddocks on an early winter’s morning.

“It gives local farmers another selling option because APP is not looking for certain varieties of faba beans or specific management styles or bean appearance or colour. They will take pulses that might not make export grade because they are shrivelled or cracked by frost, discoloured or of variable size, and pay good prices because all they are interested in is the protein content – how exciting a new opportunity for growers is that?”

SMALL TOWN, BIG VISION

Rupanyup farmer and agribusiness player David Matthews has a vision for Australian agriculture, and he is certain the $2 billion thriving pulse industry could have a big role to play.

The Wimmera Grain Company founder and Bendigo Bank board member questions whether it makes sense in a post-coronavirus world to have 40 per cent of Australia’s 25 million population densely packed into Sydney and Melbourne. Instead he believes there is real opportunity – for the benefit of both individuals and Australian society more broadly – to encourage more people to move to the regions, where housing is cheaper and life safer and less onerous on both personal health and the environment.

“But that means creating real jobs and industry in the regions,” says Matthews, a pioneer of Australia’s pulse industry and the trailblazing Rural Migration Initiative in Rupanyup, which has seen skilled farm professionals and their families from countries such as Columbia, Sri Lanka and Chile happily settle in Rup.

“Why aren’t we asking the question about what natural competitive advantages does Australia enjoy and where should we be directing government funding efforts; surely the clear answer has to be agriculture and the food industry and encouraging more secondary and tertiary value-adding food processing to be developed in our regional centres, with all the jobs that entails.”

Food is something we do so well, but we have to stop treating it like a bulk commodity.

It’s the sort of vision that saw Matthews become one of the first farmers in the Wimmera to grow chickpeas, field peas, faba beans and lentils in the late 1980s. With his chickpeas delivering good yields and a quality so high that it seemed crazy for them to end up being fed to sheep, cattle or pigs as stock feed, Matthews decided the key was to crack the human-consumption market for chickpeas and other pulses.

“So in the late ’80s, we started to bag up a few sacks of chickpeas and load them into the ute a couple of times a year and then I would drive the 300km to Melbourne and do the rounds of the (mostly Greek) companies that had started up in Clayton making hummus dips,” recalls Matthews, with a laugh.

“They’d always be keen to take them as at that time they were buying and importing all their chickpeas from overseas, and they really like the quality of what we were growing and selling.

“For me it was the first glimpse that pulses might one day become more than a sideline or boutique crop – that we might actually be seeing and helping start the beginnings of a new agricultural and food industry for Australia.”

The rise of pulse growing in the Wimmera also coincided neatly with changing population and consumer demands in Australia for ethnic foods such as Indian curries, Greek dips and salads and Middle Eastern dishes that traditionally make use of plenty of beans, chickpeas and lentils.

But Matthews knew this domestic demand was small beer compared to the opportunities on offer if the big export markets of Asia, the Middle East, India, Pakistan and Sri Lanka could be cracked.

However, with no pulse marketing body in place for such a fledgling industry, it was left to entrepreneurial growers such as Matthews and farm cooperatives in other parts of the Wimmera to take the leap into value-adding their crop for overseas markets.

Regrettably, Matthews says, not enough have followed their lead. He says he’s had enough of a world where high-quality, safely produced food has become an increasingly scarce and valued product, of watching Australia’s grains, pulses, oilseeds, meat and other agricultural produce being shipped overseas in scarcely value-added form, almost like the nation treats its bulk mineral commodities, such as iron ore and coal.

“Food is something we do so well, but we have to stop treating it like a bulk commodity,” says a frustrated Matthews.

“We also have to start acknowledging that if we as a nation are only big enough to grow enough food to feed 60 or 100 million people, we must choose who those people are and make sure they can and are prepared to pay the high prices that our processed and value-added high quality export food can command.”