How Australia’s continual dairy-industry crisis unfolded

An investigation into the causes of Australia’s continual dairy-industry crisis uncovers 50 years of controversy and consolidation. See how the crisis unfolded over the past five decades.

IT WAS a time when contactless delivery was heralded by the clink and rattle of a milk float, rather than the ping and buzz of a smartphone.

A time when the dairy co-operative model was growing in stature and influence, when Australian-owned processors were ubiquitous nationwide.

A time when Australian butter had prime position in British supermarket refrigerators. A time when a regulated market was the agricultural orthodoxy and government influence over food policy spread as far as mandated milk in the classroom.

Winding the clock back five decades to examine the progress of the Australian dairy industry gives credence to the famed Mark Twain quote: “History doesn’t repeat itself but it often rhymes.”

The Australian dairy farmer is often seen as a battler; an image held not just by suburbanites and those far removed from the land but often those within agriculture itself.

World price fluctuations, subsidised product gluts created by protectionist competitors and loss-leader generic milk in supermarkets have all played their part in shaping the battler image.

But you wouldn’t have had that impression in 1970.

In the days of kipper ties and the space race, the Australian dairy industry was doing quite nicely — even in Dorothea Mackellar’s country of intermittent droughts and flooding rains.

A quarter century of post-war prosperity had been in part fuelled by the splash of full cream on the morning Corn Flakes and the generously smeared butter on toast by a generation who knew all too well the hardship of wartime rationing.

But all good things must come to an end. The first in a series of shocks came in 1973 – when the UK entered the European Economic Community.

Retired West Australian dairy farmer and Australian Dairy Industry Council director David Partridge has often reflected on why his industry is perceived by many to be in constant crisis.

“The catalyst for me getting into (agriculture lobbying) was the entry of the UK into the Common Market,” Partridge says. “We saw our industry fall to bits, throughout Australia really. In 1973, when the Common Market entry became official, we had 50,000 dairy farmers nationally, by the end of the 1970s, six or seven years later, we were down to 22,000. It was catastrophic.”

There was worse to come. From that 22,000 at the start of the 1980s, the downward trend in dairy became entrenched. The number of registered dairy farms in the 1989-90 season was 15,396 nationwide, according to Dairy Australia figures. When the Howard Government deregulated the sector a decade later, there were 12,898 registered farms in 1999-2000.

Prolonged drought and the lack of protectionist cushioning precipitated another slicing to the registered farm numbers. In the 2009-10 season, it stood at 7511 farms and the present day number hovers around 5000.

Generational change remains a persistent problem for an ageing industry.

MORE AGJOURNAL

TOP FOREIGN INVESTORS IN AUSSIE FARMS

WHY AUSSIE FARMS ARE STRONG INVESTMENTS

Bridget and Tim Goulding operate a dairy farm at Katunga in northern Victoria. Bridget Goulding says attracting new farmers to the sector, rather than generational primary producers, is one of the great challenges for the sector.

“It’s hard for young people to get a start as a dairy farmer and I think with every year, it’s getting harder,” she says. “If you don’t have a father or some other family member to inherit a farm from, or at least partially inherit, then it’s a huge challenge to get a start and of course that dissuades a lot of good people from getting a start in dairy.

“The culture from the bigger processors is also a real problem. They’re based a long way from the farmers that supply them, often overseas, so there’s that ‘out of sight, out of mind’ factor.

“One of the great things about the smaller players that are getting a foothold is that they’ve got a better connection with suppliers and are prepared to pay a little more at the farm gate for new suppliers.”

New processor names have been popping up across Australia as brands such as Warrnambool Cheese and Butter, Bonlac and Murray Goulburn fade from the collective memory. Australian Dairy Farmers Corporation, Australian Consolidated Milk and Dairy Farmers Milk Cooperative provide an alphabet soup of acronyms but their branding is telling – there’s a commercial need to distinguish the new kids on the block as dinky-di Australian compared to the Canadian conglomerate Saputo and the Kiwi-operated Fonterra.

Old loyalties have been tested during the past decade of dairy drama.

The processor-farmer relationship has been strained since Murray Goulburn and Fonterra moved to ‘claw back’ farmgate prices near the end of the 2015-16 season.

Industry marriage counselling came in the form of the Federal Government’s mandatory dairy code of conduct, forcing processors to be held to a minimum price promise one month out from the start of the season.

Dairy Australia analyst John Droppert says no one particular factor has shaped perceptions when it comes to dairy’s “battler” image. Instead, a multitude of factors has altered the industry from paddock to plate.

“The demutualisation of the co-operatives has been one of the factors that’s fed into the market instability, starting with Bonlac in the early 2000s, followed by some smaller co-operatives and really culminating in the end of Murray Goulburn in recent times,” he says.

“The demutualisation started around the same time as deregulation; they were exclusive of one another, so it’s hard to determine which had the greater impact on farmgate prices or the sector generally, given they coincided with those changes in the 2000s and 2010s.

“The co-operatives provided that internal price stability and risk management, along with government policy, that was there in the pre-1990s period and those twin factors aren’t there today. Now much of that risk management is up to individual farmers.”

Electricity bills, council rates, transport costs – the growing cost of dairying in 2020 is another factor playing into the battler image.

Former WestVic Dairy chairwoman Roma Britnell, now an opposition frontbencher in the Victorian Parliament, says her experience as a dairy-farmer-turned-state-MP has highlighted how costs climb while farmgate figures flatline.

“Farmers are impeded at almost every stage of their business operation – energy prices, employment and WorkCover costs and red tape, increasing costs of transport because of the shocking state of roads are among the domestic impediments governments are putting in front of farmers,” Britnell says.

“All costs get passed back to farmers and for many it’s too great a burden. When I was chair of WestVic Dairy in 2005, there were 2500 dairy farmers in the South-West region alone.

“That figure is now around 1000. How long before all farmers decide enough is enough?”

That sense of frustration with rising input costs is also felt at the other end of the financial spectrum — the retail price point.

Australia Day 2011 has been burnt into the collective memory of the Australian dairy industry as the start of the dollar-a-litre decade. It further ingrained the perception of the battler dairy farmer and despite moves by Aldi, Coles and Woolworths to marginally increase generic milk prices last year, there’s still resentment from those who produce the raw material. “The price Australians pay for milk is still very low by world standards, unsustainably low,” Dairy Connect president Graham Forbes says.

Research this year by The Weekly Times adds weight to Forbes’ argument. Australian shoppers pay $1.20 a litre for generic milk, the lowest price in the developed world. Even nations that started the loss-leader trend – the UK and the US – pay higher prices after years of undercutting their respective dairy sectors.

“Most Australians are willing to pay at least $1.50 a litre for their milk,” Forbes says. “They’re more than willing to pay huge premiums on many other types of produce. You can’t keep selling milk below inflation while expecting farmers to pay input costs that are galloping ahead of inflation. It squeezes people out of the industry – that’s already happened, it’s happening now and it will occur into the future at an accelerated rate if nothing changes.”

With its low electricity costs, robust dairy co-operatives and reasonable retail pricing; it’s easy to look back at 1970 as the bookend to a golden era for the Australian dairy farmer.

But former Victorian Farmers Federation president Alex Arbuthnot doesn’t have rose-coloured glasses for the often-inefficient protectionist past.

The passionate free-marketeer, who started share dairy farming in Gippsland in the early 1970s, says deregulation has been of immense benefit to Victorian dairy farmers – not restricting the price paid in the good times as well as rewarding the efficient primary producer. But he says one thing lost from that era is the industry’s ability to sell itself to the wider public.

“Marketing is a key part of the puzzle,” Arbuthnot says.

“One of the best in the food and beverage business has long been Coca-Cola. They’re able to transform a very cheap product – a couple of cents for a plastic bottle, couple of cents for the water and sugar then sell it to the consumer at $10 a litre. That’s where we need work: marketing. I was part of the Big M campaign back in the 1970s and that was highly successful at value-adding to milk. We need an updated version, reflecting on Big M’s success and rebranding milk for the new era.”

While an optimist for the future of the sector, Arbuthnot says the twin challenges for dairy are attracting the next generation of farmers and the “social licence” of the sector in the face of rising animal activism. “You think back to 1970, or 1980, even 1990. No one questioned the role of dairy farmers producing a healthy, nutritious product,” he says. “That social perception has changed and there’s work to be done there.

“Technology has been liberating for Australian dairy farming. We’ve made huge leaps in efficiency on the back of improved technology, that’s why there’s fewer farmers. But we can’t be complacent — reform is an ongoing process.”

TAKING THE HIGH ROAD IN GLASGOW COUNTRY

IN THE lush, rolling hills of Victoria’s South Gippsland, the Glasgow family have been farming for four generations.

Bruce and Melissa Glasgow, of Bena, are the latest custodians of this lactose legacy and have seen the fortune of the dairy sector mirror their surroundings: for every price peak, there’s inevitably a value valley.

“You wouldn’t be in dairy farming, or any type of farming for that matter, if you didn’t realise there’s ups and downs,” Bruce says.

“There’s not the consistency or certainty of a nine-to-five, Monday-to-Friday job, but that’s what farming has to offer, that’s

what it has always been about.”

The Bega suppliers say picking the right processor is one of the elements in providing a financial even keel.

And you can’t rely on the weather, even in their usually fertile part of Gippsland.

“We’ve had a good summer, a good autumn and now through winter, it’s looking like we’ve had too much of a good thing. It has been a battle with some of the paddocks (being too muddy),” Bruce says.

“There’s no one reason why dairy is a volatile industry. You’ve got to have the right processor, have the right weather and manage your inputs.”

FIVE DECADES OF DAIRY

1970 Buoyant domestic and international prices, with high returns for butterfat

1973 The UK enters the Common Market, giving European farmers preferential access to British supermarkets

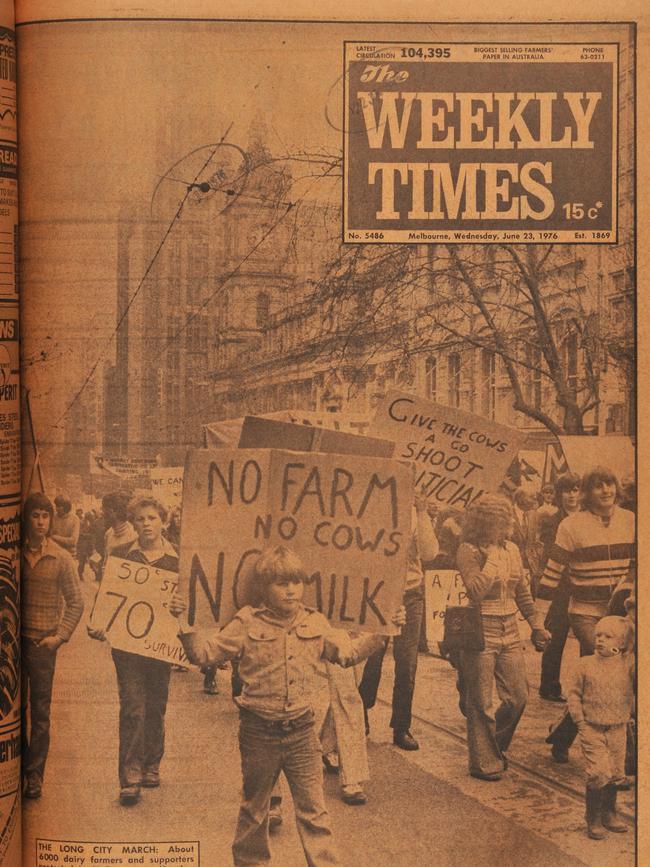

1976 United Dairyfarmers of Victoria forms as industry struggles with an inflation-led downturn

1977 Launch of the Big M flavoured milk brand in Victoria

1978 A vegetable oil-butter blend – Dairy Soft – is launched by the Australian Dairy Corporation amid the “margarine wars”

1980 Milk prices boom, with butterfat prices nudging $2 a kilogram

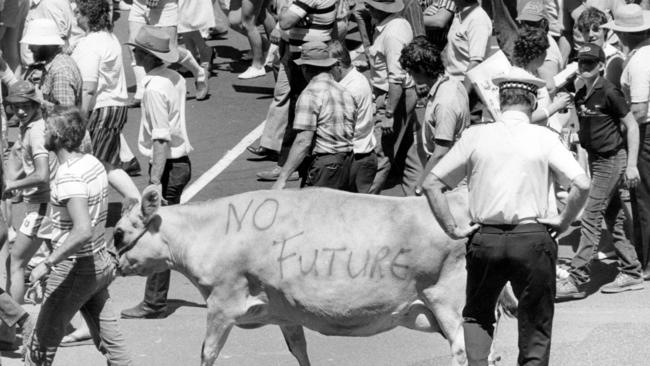

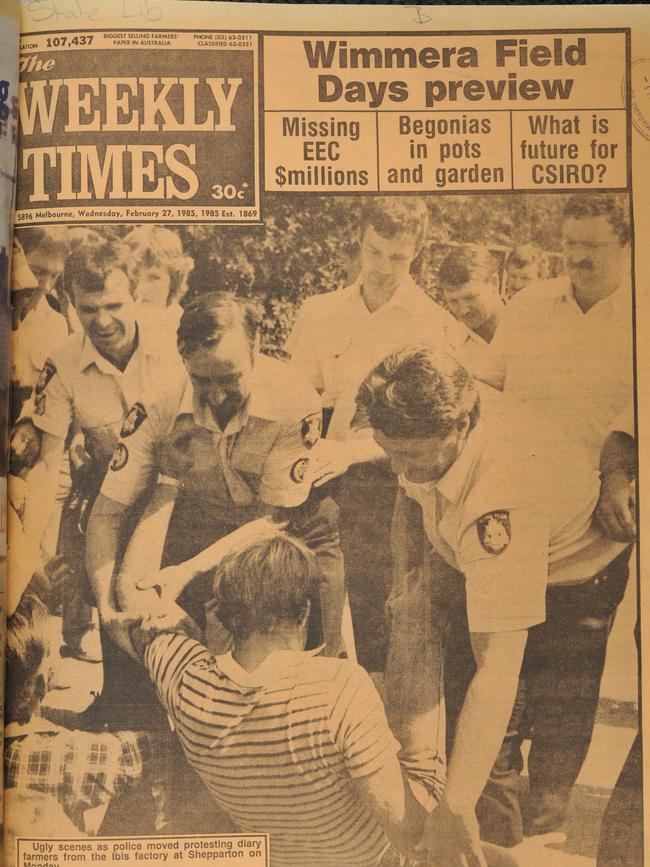

1985 Stand-off between Victorian farmers and Premier John Cain over the regulated price of city milk – kicking off the “Survive in 85” campaign

1988 Milk prices boom with improved climatic and economic conditions

1990 Thousands march on Victoria’s parliament against a Hawke Government move to deregulate the dairy sector

1992 Dairy prices boom despite the lingering effects of recession, with the dairy industry enjoying high prices for four years

1997 A dry season across much of southeastern Australia heralds the Millennium drought

1999 Deregulation introduced by the Howard Government, with an eight-year levy imposed on fresh milk

2003 Fonterra acquires Bonlac

2010 Drought breaks across southeast Australia

2011 Murray Goulburn fails in bid to take over Warrnambool Cheese and Butter. Coles, then Woolworths, launches infamous $1-a-litre milk

2014 Canadian dairy giant Saputo wins battle for Warrnambool Cheese and Butter

2016 Murray Goulburn and Fonterra “claw back” farmgate prices after a sudden drop in dairy markets

2018 Saputo takes over Murray Goulburn, after collapse of Australia’s biggest dairy company – a co-operative – after the disastrous 2016 clawback

2020 Mandatory dairy code of conduct forces processors to provide “minimum prices” a month ahead of the July 1 season start