PSP Investments, Hewitt Cattle: How foreign investors bought outback hearts

Australian agriculture’s biggest investor and its local partners have opened its farm gates to the media for the first time.

As a bush kid growing up on a family cattle farm in the Dawson River valley in central Queensland, Mick Hewitt was always prone to daydreaming.

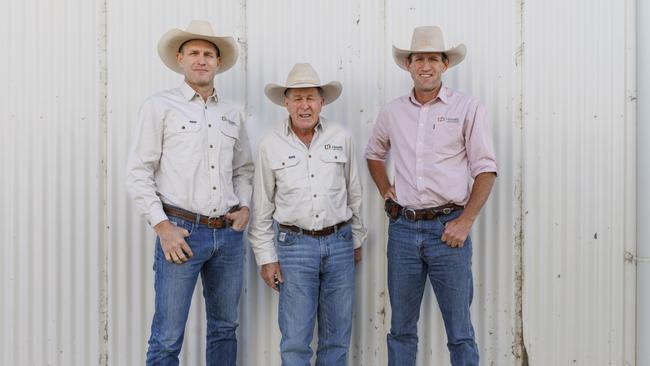

He loved the cattle and, together with older brother Ben, was a tough bush rodeo competitor, campdrafter and saddle bronc rider. But his head was often in another space.

“As a kid, our parents (Colin and Linda Hewitt) instilled in us a fierce tenacity to achieve, but it was always about creating something for future generations, not making money,” says Mick Hewitt, now chief executive of a massive paddock-to-plate organic cattle, sheep and meat enterprise, simply renamed Hewitt.

“I used to dream about sitting in boardrooms in the city, doing deals and buying more properties to create (a cattle empire) like the great pastoral houses (of Kidman and AACo); it was always my passion.”

But even the young Mick – now aged 42, clean cut, smartly dressed and flying in a corporate plane out to the Hewitt company’s flagship Pegunny cattle station southwest of Rockhampton before jetting off to New York to talk organic meat sales with big retailers – probably never quite envisaged where he and his family would end up.

In 2015, the modest Hewitt Cattle Company became the trailblazer for a flood of $6.5 billion that has been poured into Australian agriculture in the past eight years by Canadian mega-pension fund PSP Investments.

Working in partnership with local families and experienced farm operators such as the Hewitts – and using a myriad of subsidiary company names – little-known PSP Investments has quickly, and relatively quietly, become the largest player, farm landowner and investor in Australian agriculture today.

It has a huge presence in cotton and grain farming, organic meat, fruit and vegetable production, vineyards, dairy farming, walnuts, macadamias, pecans and avocados across the land.

It owns more than three million hectares of farmland, from vast outback cattle stations to prized small vineyards in South Australia, is the biggest owner of irrigation water entitlements in the Murray Darling food bowl, and is collectively one of Australia’s biggest producers of food and rural exports in Australia.

But despite PSP’s size and foreign investor status, in the small world of Australian corporate agribusiness today it is rare to find a bad word spoken about their influence, priorities, modus operandi or actions.

“PSP is just a class act; we are lucky to have them here,” says usually cynical agribusiness adviser David Williams. “We should be grateful they have invested so heavily in agricultural assets because, when they buy these things, they then spend significant capital with their partners in these properties, to improve the land and make them more sustainable and productive.

“They also hold ownership of those assets and stay the game with a 20-year plus view.”

At the time Mick and Ben Hewitt were looking to reshape their cattle enterprise to attract investment-ready outsiders to partner with, the Australian business world was just waking up to the potential of the languishing sector.

But outside capital willing to invest in Australian agriculture has long been in short supply. A landmark report commissioned by the ANZ Bank in 2012 estimated Australian agriculture desperately needed inflows of more than $300 billion in capital by 2020 if it was to modernise, grow and thrive become a powerhouse of the national economy.

But with Australia’s superannuation funds largely of the view that the agricultural sector was too volatile and risky an industry in which to invest, despite the persuasive “Global Food Story”, it was left to foreign money to fill the gap.

Yet in 2015, Chinese-owned state enterprises, wealthy international families, foreign governments looking to lock in a reliable source of food for their people, and agnostic pension and investment funds seeking good safe financial returns on capital had started to sniff around the agricultural scene.

Big investment companies such as Westchester, the Singapore government’s Temasek and Harvard University’s Endowment Fund saw farmland in particular as promising.

“PSP has really gazumped (in their large-scale investment) all the Australian super funds who prefer to own a block of flats on Fifth Avenue in New York than an Australian farm,” Williams says. “And they’ve absolutely shown that if you work with good local operators and think long-term, you can more than see through the volatility of the agricultural cycle and make good returns.”

Even so, the Hewitt family did not expect it would be the Natural Resources arm of Canada’s giant Public Sector Pension Fund, with its $270 billion of superannuation fund reserves, that would come knocking at their farm gate.

Unlike many other foreign investors, PSP did not just want to buy Australian farmland for its potential capital gain and disinterestedly lease the agricultural operations on its surface back to local farmers who would pay rent.

Instead, PSP was looking for business partners. It actively sought out top-tier farm owner-operators, preferably families, already running successful businesses but who lacked the capital – or who did not want to take on more bank debt – to expand, achieve scale efficiencies, and produce enough food to have clout and supply reliability in major markets.

It also wanted the families involved to retain a financial stake in the new joint venture, to continue to have “skin in the game.”

Mick Hewitt says in hindsight, he is always grateful that Hewitt Cattle Company and PSP Investments found each other. His family, who then owned just four cattle stations, had spent several years meeting with dozens of prospective investors and companies. But none really grasped their family’s vision.

“PSP were greatly respectful of our skills, our family history and our passion for the industry,” says Hewitt, whose family has run cattle in central Queensland around Theodore and Moura for four generations and 120 years. “They ‘got’ us and what we hoped we could achieve.”

Since then, the joint venture has boomed, making major cattle station acquisitions almost monthly to add to its might.

The Hewitt group now runs more than 120,000 cattle across more than 2.2 million hectares, employs 300 staff and owns more than 20 major aggregations of groups of cattle and sheep stations from Julia Creek in the Gulf Country to central Australia and northern NSW.

It has spent more than $500 million since the early days expanding its reach, also now including free-range pigs and organically raised sheep.

Business-transformational purchases have included the $96 million acquisition in 2022 of four giant Central Australian cattle stations covering 1.1 million hectares northwest of Alice Springs – one of largest organically certified land parcels in world; its snapping up of historic Tubbo sheep station in NSW’s Riverina in 2021 for $40 million, and part-purchase of Arcadian Organic & Natural Meat company and its market leading Cleaver Organic retail brand in 2017 for $50 million.

“If a consumer in Europe or the United States wants to dedicate their shopping choices to sustainable outcomes, I want to be able to deliver that,” explains Mick Hewitt, as he watches his organic grass-fed cattle that are never drenched or vaccinated graze alleys of buffel grass between rows of leucaena bushes on Pegunny station.

“That’s what the partnership with PSP has allowed us to do.”

Neither PSP nor the Hewitt family will discuss the exact stakeholding each entity holds in the partnership.

But Mick Hewitt says in many ways it is an irrelevant figure, since the relationship and trust built between the partners isn’t based on financial clout.

“(PSP’s) business model is pretty simply; they’ve done an excellent job of finding the best-in-class operators and farming families across a range of agriculture in Australia and partnering their capital with them, but always with regard for the environment and long-term sustainability.

“While they rightly demand we run a sophisticated progressive business with great governance and skilled management teams in place, the general sense has always been that PSP is there to co-invest further with us, if and when we identify the right strategic assets and investment opportunities to buy and expand as they become available.”

Head of Agribusiness Ben Hewitt, who manages the vast Hewitt station network, is also quick to dispel any notion that their expanding business has unlimited “rivers of gold” at its disposal because of PSP’s deep pockets and fund size.

“We are very much shareholders too; the bulk of our family wealth is in this business and the people who work with us know that if they are spending a dollar, it’s a Hewitt family dollar and no one else’s,” he says.

“We don’t put one cent of PSP money where we wouldn’t put our own.”

It’s a quiet Friday morning in downtown Montreal as many of the workers in the most-locked-down-city-in-the-world-after-Melbourne during the pandemic continue to toil from home ahead of a welcome long weekend.

But high on the 14th floor of a shiny tower in Montreal’s financial district, the man who controls a huge slice of Australian agriculture, its farmland and the food it produces, is at his desk surrounded by computer screens.

Marc Drouin is global head of natural resources investments at PSP Investments, which manages more than $270 billion of pension plan funds on behalf of the Canadian government.

The massive money pool, which will grow to $370 billion by 2030, forms the future retirement pension payments – akin to Australia’s compulsory employee superannuation schemes – of Canada’s 357,000 federal public servants, its 68,000 defence force personnel and its federal police force (the famous Mounties).

With a mandate to protect and grow the huge pension fund in the best interests of future beneficiaries, “achieving a maximum rate of return without undue risk or loss”, Drouin is charged with investing about 8-10 per cent of the total fund into safe and long term natural resources assets such as agriculture, timber and aquaculture.

He has $22 billion ($C19.5 billion) already invested. About $5.5 billion has bought timber plantations and reserves in Canada, Chile, Brazil and New Zealand. The rest, more than $16 billion, is allocated to agriculture and aquaculture. And, to the benefit of the capital-starved local agriculture sector, nearly half has ended up finding a safe home in Australia.

“We are very comfortable investing in Australia and in agriculture; we understand agriculture and its volatility but we are long-term investors and rural land values provide great stability,” Drouin told AgJournal in an exclusive interview.

“We find Australia very investment-friendly, it’s a stable regime and the investment rules and land tenure clear. We have also proven that we can obtain scale in investment in agriculture here, which many of the big Canadian pension funds were sceptical about.

“But most importantly, we have found a wonderful group of like-minded people to partner with us – local family operators like the Hewitts, the Robinsons, the Casellas, and the Simonettas – who are really great at what they do.”

From a small start in 2015 when Drouin first entered Australia with just $400 million to invest in Australian agriculture – its first partners were the Hewitt cattle family – PSP Investments has grown to become a diversified juggernaut.

Its associated divisions, specialist companies and commodity platforms built up and consolidated over the past eight years are the public face of PSP Investments in Australia.

Intentionally or not, they serve to largely shield the single-handed might and long tentacles of the Canadian pension fund from the public. “We have flown under the radar a bit,” Drouin admits.

As well as natural and organic meat division Hewitt, there is PSP’s nut growing and processing specialist company, Stahmann Webster, with its major presence in walnuts, pecans and, in the future, macadamias, that PSP bought in 2017 when it was a relatively small and cash-constrained pecan grower at Moree.

Its large-scale cotton and irrigated cropping division, Australian Food and Fibre, run in partnership with highly experienced cotton growers David and Joe Robinson, was formed after PSP bought ASX company Websters for $854 million in 2019, and delisted it from the Stock Exchange. In 2021 it added the cotton farms, five gins, brand and marketing arm of Auscott to AFF’s assets in another estimated $500 million deal.

Another key PSP division is Southern Premium Vineyards, which last year bought 35 vineyards from the Casella family in Griffith, in a deal that will guarantee the Casellas’ long-term supply of grapes for their global Yellowtail and Peter Lehmann wine brands, for more than $150 million.

Through its Fresh Country Farms arm, run by chief executive Nick Gill and with accumulated horticultural assets in excess of $2 billion, PSP also owns a minority stake in Perfection Fresh, the fruit and vegetable growers, suppliers and wholesaling business founded by the Simonetta family.

FCF has also bought extensive avocado farms around Bundaberg together with the Simpson family, and also spent $860 million buying almond plantations and irrigation water from Olam in a leaseback deal. Its newest division, PSP’s broadacre cropping arm, Altora Ag, was formed this year after PSP Investments acquired and merged BFB and Daybreak Cropping to create Australia’s largest grain-grower and broadacre cropping business with more than 153,000 hectares of cropping land, grain storages and trucking fleet in NSW and Western Australia.

“We didn’t set out to be the largest (player) per se, but achieving scale and a good spread (of locations and commodities) is important if we are to make the most of synergies, spread risk and to continue to grow and invest,” Drouin says. “We like diversification — we like being across (everything) from the crops to grazing and tree nuts to glasshouses.

“But we are very long-term investors. We are not about buying an asset, prettying it up and quickly selling it off; part of our ethos is we want to use our capital not just to produce food but to improve our assets, help the transition to carbon net zero and be good stewards of the land we own and operate.”

David Williams admires the way Drouin has such trust in his Australian farming partners such as Mick Hewitt and Joe Robinson, that he allows them to make quick purchasing decisions, ensuring opportunities to buy good farms for sale are not missed because of time zones or corporate bureaucracy.

“I have enormous respect for him; he’s very analytical and very rigorous but he also doesn’t pretend to be a farmer,” Williams says. “But he’s absolutely across it all; there wouldn’t be much happening at the big end of agriculture, not just in Australia but around the world, that Marc Drouin doesn’t know about.”

At his desk overlooking Montreal, a relaxed bilingual Drouin puts it even more simply.

“I’m not a farmer or an agricultural expert, I’m a fund manager and financial investor. Our local partners and operators are integral to our growth and our success.”

Ross Burling still remembers the thrill three years ago of driving on to a freshly harvested cane farm at Bucca, west of Bundaberg, and realising what a perfect site it would be for a seriously large greenfield macadamia plantation.

Today the vision of Burling, CEO of Stahmann Webster, has come to fruition, thanks to the $1 billion of capital injected by the Canadian pension fund that has allowed the former small pecan business to rocket into the big league of the fast-growing, but still nascent, macadamia industry.

Neat rows of healthy macadamia seedlings, carefully irrigated with drip tape and planted in deep compost beds, stretch to the horizon. More than 800 hectares has already been planted with seedlings bred in Stahmann Webster’s own nursery; a capital-intensive initiative totalling more than $17 million with hefty establishment costs of $22,000 a hectare.

The next 150 hectares will take Stahmann Websters total macadamia holdings at Bundaberg to nearly 2300 hectares – it recently also bought the majority of the operations of local grower and processor Macadamias Australia for more than $100 million – and eventual commercial production to 7500 tonnes a year of the high-value native nut.

It will transform Stahmann Webster, a relatively late arrival on the hot macadamia scene, into one of the biggest growers in Australia, a title it already holds in for both walnuts and pecans.

But Burling says it is not enough just to grow nuts well; together he and PSP are aiming to farm all of their nuts in the most sustainable, environmentally friendly way. Nut shells left after processing are being turned into biochar – Burling calls it “soil viagra” – to incorporate back into the soil. Friendly insects are used to control pest numbers, grass growth is encouraged between rows to reduce water use and most irrigation water used on its Bundaberg farms is recycled and prevented from running off.

While Burling believes the focus on composting and manure is already delivering carbon-zero status to his nuts, all carbon emissions and carbon storage is now being measured and independently audited before Stahmann Webster can claim that status.

“We are growing a product – nuts – that consumers eat because it is healthy, so we want to take that philosophy right through to our farms and every step of the way we produce our nuts,” Burling says. “And we don’t just want to do the right thing by our consumers but by the planet as well.”

All of Stahmann Webster’s nut farms are currently being audited by independent global organisation Leading Harvest to certify its environmental stewardship credentials, in a specialist program designed to harmonise Environmental Sustainability and Governance reporting in agriculture across the world. All of PSP’s Australian operations are taking part.

“PSP has very strong views on the environment and the future world which is reflected in our approach to improve our soils and all of our systems,” Burling says.

Back in Montreal, Marc Drouin says that while PSP natural resources division does not yet have a target date by which it will guarantee its operations will be carbon net zero, it last year launched a decarbonisation and climate strategy to transition towards that target as soon as possible.

“Our view is that we want to use our capital to help (the world) transition to net zero,” Drouin says. “We are very cognisant of the need for a continuing social license to operate and to be good corporate citizens in the communities where we work and live.”

Drouin says he is very conscious that as the biggest foreign investor in Australian agriculture, public attention may one day focus on Canada’s PSP Investments’ $6.5 billion size, and it if owns too much of the agricultural pie.

“I get the sense (from FIRB) that Canadian pension funds are of the ilk (of foreign investors) the Australian government is looking for,” Drouin says.

Back on their cattle farm near Theodore, Mick Hewitt laughs when asked why all of PSP’s Australian offshoots, including Hewitt Foods, are tagged as reclusive.

“We do fly under the radar, but we’ve always said in the past we’d rather let our actions do the talking,” Hewitt says.

“But now I’m not sure humility always serves you best. Because we have a great story to tell.

“PSP’s investment has allowed us to become not just the producer of the most sustainable and natural meat in Australia, but we believe in the world.”

“That’s what foreign capital and a great partner can do.”

LABOUR PAINS

Thousands of avocados are tumbling along the automated sorting lines at Simpson Farms’ main packing shed near Childers, south of Bundaberg.

It’s near the end of the harvest – a tough one for the family business given the low retail price of avocados this year at close to $1 each. One bright spot this season has the sweeping return of foreign backpackers and casual labour to the Bundaberg fruit bowl after three years of closed borders.

Young travellers from England, France, Germany, Korea and Japan are busy in the orchard harvesting, or in the packing room sorting firm Haas avocados into packing boxes ready for truck pick-up.

Simon Grabbe, Simpson’s farming head, says that with its 770 hectares of avocado orchards producing 45 million avocados a year, the business ideally employs up to 250 casual workers all peak season from February to July.

Grabbe is relieved that this year the labour situation is back to normal after two seasons of dire shortages, with as many as 800 local and foreign individual backpackers working for them at different periods throughout the season.

“The hostels in Bundaberg and Childers are full again and it’s just great to have (the backpackers) back here in the orchards and sheds and earning money so they can head off after they’ve worked here for a few months on their travels, usually up the coast to north Queensland for the good weather and party scene,” Grabbe says.

“It means we are no longer having to worry day-to-day if we will have enough labour to staff our farms and operations.”

Simpson Farms employs all of its casual labour directly, rather than through often-discredited labour-hire companies. Grabbe says while this involves a lot of online data and paperwork, it ensures all of its employees are paid fully and correctly, as well as makes checks of visa employment conditions easy.

Simpson Farms uses the global Sedex quality assurance certification program to audit and verify its labour employment systems; a data compliance system being increasingly required by customers such as supermarkets and export markets.

“Our customers are demanding to know we are doing the right thing; ESG is becoming an incredibly important part of the right to operate a business these days,” Grabbe says.

PSP’S $1 BILLION WATER POOL

As the biggest cotton, walnut and pecan grower in Australia, it comes as little surprise that Canada’s PSP Investments singly also owns the most irrigation water in southern Australia.

The pension fund’s massive water rights are held in several different divisions of PSP’s vast Australian agricultural business, making it difficult to calculate in gigalitres of annual flow. But it is estimated the total value of irrigation water owned by PSP and its linked entities and arms now exceeds $1 billion.

In the Murray Darling Basin, irrigated cotton crops, grapes, orange trees, vineyards, almonds and walnuts on PSP-owned land depend on the precious water rights it has acquired over the past decade. Around Bundaberg in Queensland too, PSP is a major user of water from the Burnett River system and Paradise Dam. In South Australia and Tasmania, its greenhouses rely on irrigation, as do its vast cotton operations.

But, unlike other Australian water barons and corporate water holders, PSP Investments insists it only ever uses its ownership to grow food and crops.

PSP’s Marc Drouin says this is a deliberate strategy and company policy, across all its divisions.

“Owning water is critical to us; it’s great to have high quality land but if you haven’t got access to water to irrigate it, it puts you in a very bad place,” Drouin explains, saying he has only admiration for Australia’s “cap and trade” system of water rights, which he believes provides the most transparent water availability and pricing regime in the world.

He says it is unique in the way irrigation water rights have been separated from being linked to specific farmland, and can be relatively freely traded up and down large river systems, resulting in a pricing mechanism that ensures precious water is valued, used efficiently and, in times of scarcity, goes towards growing or protecting the highest-end value crop.