Glenfalloch Station: What makes the Gippsland property an Aussie icon

The Gippsland station is a jewel of southeast Australian farming. Here we’re given an in-depth look on what makes it so special.

Iconic. Now there’s a word that gets overused. Few things miss the iconic touch nowadays, particularly in rural Australia.

Iconic location, iconic event, iconic people, iconic moment, iconic farm. That last one gets a real good run.

But there are few Australian farms that actually deserve the mantle. Think Victoria River Downs in the Northern Territory, Collinsville in South Australia, Pooginook in NSW. And Glenfalloch in Victoria.

Nowhere near the size of its more expansive cousins, Glenfalloch is one of the jewels of southeast Australian farming.

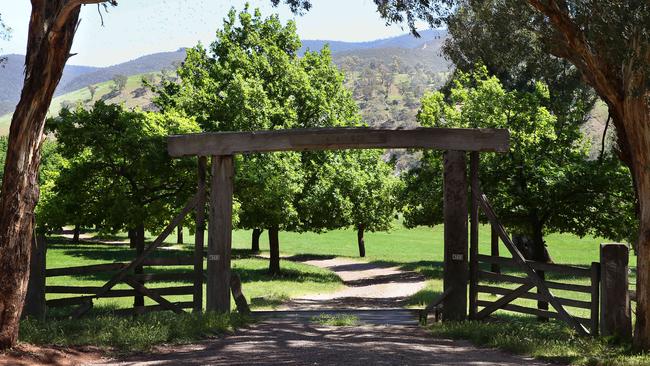

Glenfalloch occupies a 25km-long sliver of grazing land split by the Macalister River in the lower High Country of Victoria’s central Gippsland. Bordered each side by steep mountains that form its natural boundary, it uniquely occupies an entire valley downstream of the small town of Licola (which was once itself part of Glenfalloch Station), and upstream of Lake Glenmaggie.

At 4860 hectares of freehold land, or 12,000 acres (nearly 50 years since metric measurement, old habits are hard to shake), it’s not a big farm by Australian standards.

But in a region dominated by dairy farms and, increasingly, vegetable operations, it’s hard to find bigger. Observers put it second in size to Omeo’s Cobungra Station – 50,000 acres, or 20,234 hectares, of freehold and leasehold – as the biggest farm east of Melbourne.

But it is not size that matters.

What matters here is history, productivity and its role as one of those special properties where locals almost feel they own some of its soul, where thousands who pass Glenfalloch on their way to the rugged High Country, draw deep breath at its sheer beauty.

Glenfalloch was settled in the 1840s, when settling such a remote run would not have been so peculiar, as even the urbanised and cleared areas we know today would have been remote.

But while those areas developed through gold rushes, irrigation schemes and town settlements, Glenfalloch has stayed pretty much the same for 180 years. Its topography would look the same as it did in those days and it still has no mains power or connection to services.

After a handful of quick ownerships, Glenfalloch fell into the hands of Edward Riggall in the early 1870s. Riggall’s brother, Richard, ironically, owned the aforementioned Cobungra Station.

Riggall owned Glenfalloch for about 40 years before it was bought by the Gilder family, who held it for 104 years before selling to the Paul family in 2015 for a rumoured $12 million.

“That sounds about right,” says a smiling Dane Martin, the manager of Glenfalloch.

“You’ve got to ask yourself where you would find yourself $1000 an acre country now? You can’t get it.”

Glenfalloch was purchased by the late John Paul and his wife, Mary, as a “hill block” to complement the family’s Docker Plains Pastoral beef operation in Victoria’s North East.

In late 2014 Dane Martin, who oversees the Paul family’s operation, saw a story in The Weekly Times about Glenfalloch being for sale, and pinned it up in John Paul’s office. “He’s come past and did a double take and said: ‘You’re not serious are you?’ and I said I don’t know, I just put it there, you said you wanted a hill block. And he said righto, and that was it.”

John Paul, who passed away not long after the deal was done, knew the property well, having stayed there as a boy on his way to hiking in the High Country.

“He was hellbent on buying it – nothing was stopping him,” Martin says.

Rob Gilder was the last of four generations of his family to hold the reins at Glenfalloch.

“I had very mixed feelings,” Rob says of his decision to sell.

His father had passed away in 2000 and the latter years of the Gilder ownership was punctuated by bushfires in 2007, followed just months later by surging floods that decimated fences and saw stock losses as high as 200 head.

He says it was also becoming increasingly difficult to raise young children in such a remote location.

“There is no school bus, there is no school, there is no community, little internet, no electricity, no mobile phone service. Sixty years ago none of that really mattered but now it does.

“I was the custodian of it. So it was on my head when I sold it. I felt terrible in one sense but I was very fortunate. I had a terrific life there.”

Rob’s great-grandfather, also Robert, bought Glenfalloch in 1911, and for most of that time was run in tandem with the family’s other notable property, Mewburn Park, near Maffra.

And, as the wheel has turned, it is now part of another dual-property beef production system.

Glenfalloch immediately doubled the size of the Paul family operation, which is based at the historic 4000-hectare property, Bontharambo, near Wangaratta, almost due north across the Great Dividing Range.

“The synergies between all of them work really well,” Martin says. “Not only have we got a geographical spread, we have a different rainfall spread as well. If it’s ordinary up at Wangaratta it’s usually pretty good down here or vice versa.”

Glenfalloch is no show pony. It is a breeding property, running 1200 Angus breeders and 400 heifer replacements. The Pauls run another 1300 cows, 400 replacement heifers and 120 stud cows at Bontharambo, along with 1000 first-cross ewes.

Under the Gilders, Glenfalloch was also a beef breeding operation – Hereford then Angus – and had a flock of about 10,000 Merinos. But wild dogs have put paid to the sheep.

“We identified early in the piece that the wild dogs were not going to go away, so that was the end of that,” Martin says, echoing a common refrain of those bordering crown land across the nation. “It is hard to make money out of sheep that the dogs keep eating.”

Plus, he says, cattle are less punishing on the hills, and spread less weeds across the property.

The Docker Plains operation is relatively simple, yet effective. Bontharambo is home to the 100-year-old Bontharambo Angus stud, started by Mary Paul’s grandfather. It is a closed stud, without any modern influence, making the bulls shorter and squatter than today’s Angus, ideal to put over the first-calving heifers for birthing ease.

The breeding cows are joined to Landfall sires, one of the biggest names in Australian Angus genetics. Martin says the Tasmanian stud’s bulls give offspring the desired growth rate.

“We don’t want a huge mature cow weight because we feel that is going in the wrong direction,” he says. “It’s giving us great carcass characteristics, so we are getting a little bit of rib and rump fat back on them. Our eye-muscle area has increased and marbling, at 2.8, is really good.”

Calves are then taken to a fattening block at six to seven months age – a 320-hectare high rainfall property at Thorpdale, 1.5 hours east of Melbourne, for the Glenfalloch calves and a 320-hectare property at Oxley for the Bontharambo calves – where they are fattened and sold into the Coles Graze program at 14-16 months and ideally 450kg. Some go to JBS for further fattening at 12 months of age.

“We punch the weight into them and then they are gone,” Martin says. “We seldom put cattle into the saleyard – it is all direct. It is all about building relationships. If they are happy with the product we are producing they will be back for more.”

The Glenfalloch and Bontharambo operations are virtually run as one. “Bulls go out on the same day, the genetics are pretty much the same,” Martin says.” Landfall helps us with that, identifying which sires are going to be the best for us here.”

Glenfalloch’s future lies in preservation: of its history and its environment.

On the latter, the Paul family embarked on an extensive program of tree-planting and fencing off waterways.

“That’s the legacy of John and Mary Paul,” says Martin. “They started their environmental works back in 2005 and it has grown since then, and we have adopted the same principles they wanted to see on all four farms.

“These days it is becoming more evident that that is a very important thing in terms of not only protecting the assets, stopping erosion, stopping that nitrate leaching, we are putting something back into the environment.”

But there is also a commercial imperative for Docker Plains.

“The next challenge for agriculture is looking at ways we can improve from a climate change point of view. Certainly the carbon-neutral goal that Meat and Livestock Australia is putting forward, that is very important to us.

“The whole place is solar powered, all the pumps in the river are all solar powered. We don’t do any ploughing at all. We are rotationally grazing, trying to keep a good layer of vegetation on our soil so it doesn’t blow away. So we are trying to do all the right things to preserve the land and water.”

Martin and his team are mapping the property, marking the site of the original homestead and landmarks, and repairing an old cattlemen’s hut on the property.

“We are keen to preserve what history is left.”

And you can feel that history as you walk around the not grand, yet homely homestead, the feeling of a place that has a story to tell – of owners past, of hundreds of workers who endured the isolation of the place, but proudly say they worked at Glenfalloch; of its own little town where children were raised and schooled in the farm’s schoolhouse.

But would those storytellers agree that it was a truly iconic property? The two men who hold the closest link to Glenfalloch say that is an emphatic yes.

“It would have to be in the top 20, just for its sheer location and the history behind it,” says Dane Martin. “It is a beautiful place; I think it’s the prettiest place in the world, really.”

“It’s steep and unforgiving and difficult,” says Rob Gilder in a candid assessment, “but I never got sick of the physical beauty of the place.

“It is a fabulous property, a beautiful area and great local people. I don’t ever hope to equal it in anything I do.”

LEGEND HAS IT

Few places are shrouded in mystery as heavily as Wonnangatta Valley.

Situated on the Great Dividing Range in eastern Victoria, it is a 450-hectare relatively flat stretch of pasture about 30km east of Mt Buller as the crow flies, but the drive would be more than 200km via unforgiving bush tracks and river crossings.

Yet even the crows would be wary of this place, with two mysterious disappearances that have defined its legend.

In 1917 Jim Barclay, manager of the valley’s Wonnangatta Station, and farmhand John Bamford travelled 30km to the now extinct town of Talbotville. That was the last time the men were seen alive, with Barclay found some months later in a shallow grave with a shotgun wound. Bamford was found about a year later, about 20km from Wonnangatta, with a gunshot wound to the head.

The cases were never solved. And neither has the modern mystery of Russell Hill and Carol Clay (pictured), who disappeared while camping in Wonnangatta Valley early last year.

Across the latter part of last century, Wonnangatta was linked to Glenfalloch, when Bob Gilder bought the freehold to Wonnangatta in 1969. With that came about 40,000 hectares of leasehold High Country.

The Gilders used this land to fatten steers, with up to 1000 Glenfalloch cattle roaming the high country lease over summer. But by the 1980s, the environmental movement was agitating for cattle to leave the High Country, claiming the cattle hoofs were damaging waterways and natural vegetation.

It’s an argument Rob Gilder can understand, but believes the situation could have been better managed to allow cattle to stay in some form.

His father, Bob Gilder, offered to sell Wonnangatta to other High Country families, but there were no takers. So he offered it to the Victorian Government, who bought it in 1988.

It was around this time all High Country cattle grazing came to an end, although debate rages about its impact on the environment in the face of wild brumbies and deer roaming the mountains.

The most remote freehold cattle station in Victoria became part of the Alpine National Park, and with it an end of an era. But not its mysteries.