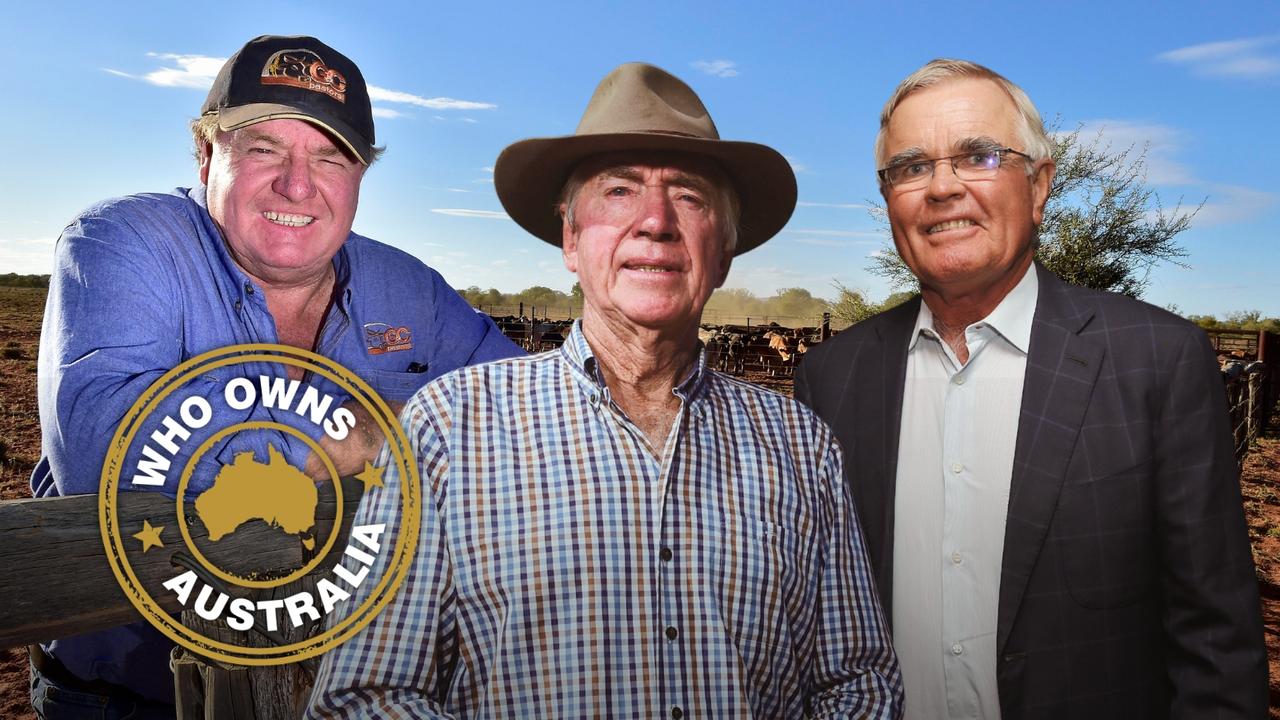

How Roger Fletcher went from rags to riches with multi-million dollar agribusiness empire

Roger Fletcher and his family have built an incredible agribusiness empire. Here’s what he has learnt along the journey to becoming Australia’s biggest sheepmeat processor.

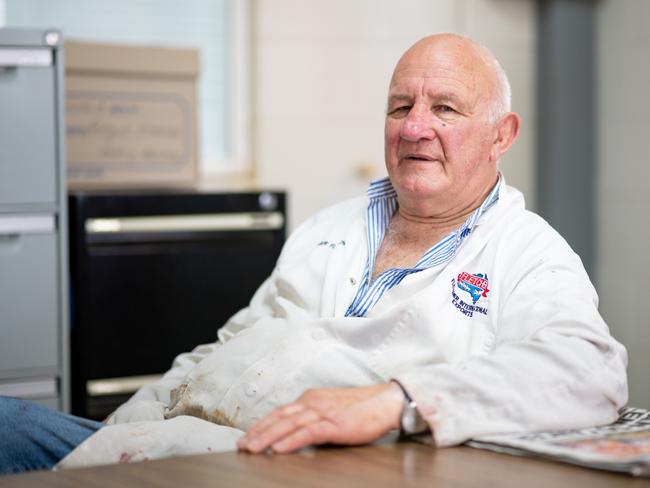

IT’S a Friday afternoon in Dubbo and a knockabout bloke in jeans and a work shirt, with a broad smile on his weather-beaten face and a nose that has seen better days, is walking down the main street with a dead sheep draped over his broad shoulders.

He doesn’t get a second glance from locals as he ducks inside a small Indian restaurant, where he is warmly greeted by its owner. It’s not every customer that gets such a direct delivery of their lamb order from Australia’s biggest sheepmeat processor, multi-millionaire, meat industry icon and Dubbo’s largest employer, Roger Fletcher.

“They’re good loyal people who’ve been buying from us for years,” says Fletcher’s daughter Melissa, 45, with an understanding shrug and fond laugh at her father’s unconventional antics. She is now chief executive of the Fletcher family’s sprawling agricultural empire, Fletcher International Exports, born out of a bush-droving business started by Roger and her mother, Gail, more than 50 years earlier.

But it’s exactly such a down-to-earth approach to his customers and personal touch that has made Fletcher, 75, one of the nation’s most successful, respected and wealthy agribusinessmen today.

It also demonstrates two of Fletcher’s greatest strengths; understanding exactly what his long-term customers wants, and personally knowing each of them well enough to drop in and chat – whether it is in Dubbo, Bahrain or China.

“It doesn’t matter if it’s the Prime Minister, the Emir of Qatar, Kerry Packer or the local restaurant owner; Roger treats them all just the same,” says western NSW federal MP Mark Coulton, a Warialda sheep farmer who has known the Fletcher family for decades.

“His is an extraordinary rags-to- riches story; how he started out in life with absolutely nothing, and now owns the two largest sheep processing plants in Australia, is one of biggest landholders and grain dealers in NSW, exports millions of dollars of meat to countries around the world every week, and is the biggest employer in Dubbo by far.

“But there’s no airs and graces with Roger; he’s more happy talking to his workers – and he knows almost every one by name – than he is hobnobbing around.”

The Fletcher empire now extends far and wide. More than 1300 employees work for the business in NSW, Queensland and Western Australia. It is vertically integrated across the agricultural sector, from growing crops and sheep on their own farms, to processing food, transport, shipping and sales direct to customers.

FIE’s two state-of-the-art sheep and lamb processing plants – one built in Dubbo in 1988 and the other in Albany, WA, a decade later – process more than 4.5 million sheep a year, making the family-owned company the biggest buyer of sheep and processor of lamb in Australia.

Where once they had one processing line in each factory, culminating in shipping entire frozen lamb carcasses around Australia and overseas, there are now 100 lines of products using every part of the sheep. Nothing is wasted and the value of each lamb, which can end up being eaten by 62 different customers, has soared.

All sheepmeat is Halal-certified, with cuts tailored to customers’ specific needs and shipped direct chilled in food-ready packs, boxes and containers around the world, including to cruise companies, restaurants, airlines, Coles, Woolworths, China’s elite and the Middle East’s royal families.

When the family started buying farms to produce their own lambs to even out supply to its abattoirs – it now produces 3-5 per cent of its total lamb throughput from its farms and feedlots – many of the properties also grew wheat and other crops.

So Fletcher started buying grain and pulses from other farmers to add to his own relatively small production and trading them globally too. Cotton soon followed, allowing FIE to fill whole trains from Dubbo to Sydney port with its own Fletcher Dubbo-branded containers loaded with meat, grain and cotton. The dedicated Fletcher Rail Freight terminal at Dubbo and freight intermodal hub came next.

Frustrated with expensive and inefficient train services, in 2015 Fletcher bought his own new locomotives and 160 rail flatcars to more quickly carry his containers to Port Botany himself.

He now runs three trains a week to Sydney, and backloads fuel to country NSW on their return trip. Similarly, some of his shipping containers are sent back to Australia loaded with imported cement powder, with a cement blending plant at Dubbo now towering over his freight hub. A huge grain bunker and cotton storage facility has recently been added, as well as natural gas pipeline supply.

Fletcher’s future visions include using renewable hydrogen and solar power, supported by batteries, to allow for 24-hour meat processing. A lithium battery manufacturing plant, one of the first in Australia, using lithium and other rare earth metals mined in western NSW is tipped to follow next.

“It’s a hard complex business running an abattoir; everything we do is linked and vertically integrated; we are in agriculture and transport,” says Fletcher. “I can’t control the government, the wharves, the electricity grid or the railways – all those things that are so hopeless and inefficient – but I can run my own trains and my own show; you try and control what you can.”

It’s a philosophy that has seen Roger Fletcher quietly rise to the top of Australia’s agribusiness world. He and his wife and sole business partner, Gail, and their three adult children, Pamela, Melissa and Farron, all work in Fletcher International, which remains an entirely family-owned private company.

Meat industry leader Richard Rains describes Fletcher as a “true genius” and “absolute warrior.” “He has come from rock-bottom rural poverty and with limited schooling to rise to the top of the meat industry and Australian business; it’s a testament to the man – and to Gail – that they have had the foresight to invest heavily in things unheard of, whether it was setting up a new meatworks in 1988 at a time when all the council abattoirs were going broke, or to buy their own trains.

“His is a most extraordinary Australian story, yet it is not well known outside agriculture; what he has done and quietly achieved for the meat industry, for Dubbo and for Aboriginal people in particular is incredible.”

Fletcher’s life has the elements of a fable about it. As Fletcher explains, his childhood in the late 1940s and early ’50s had nothing easy about it, except for the benefits of a close-knit family. He was the second born of six children; his parents “eked” out a subsistence living on a small rough sheep block near Glen Innes. There was a big vegetable garden and meat to eat, but no running water, electricity or phone.

His mother, who he adored, trained horses to earn a bit of extra money. The kids helped out droving mobs of sheep on the stock routes in dry times.

“It was hard going, but I was a tough little bugger, and my mother was a good teacher,” says Fletcher. “She taught us how to save and work hard, how to make-do with what you have and not to waste anything, and the importance of having values and respect. Those things have stayed with me right through my life and stood me in good stead.

“I think that sort of early upbringing gives you the challenge to go forward and do things with your life.”

But it was Fletcher’s own early prowess at local rugby games that got him thinking about the unheard-of possibility of going away to school in Tamworth, more than 200km away from his home and family. He was 12, stubborn and ready to use his savings from catching rabbits to pay to get to Farrer Memorial Agricultural High School, a government boarding school that excelled in both of Fletcher’s obsessions at the time, farming and rugby.

“I was the only one of my family to leave home to go to school; it gave me a great education – I still have an association there – and opened up my mind to the world. And I had a good rugby coach.”

It was from his rugby days – he excelled at Farrer and later was a star of Moree’s championship-winning team for many years as well as a short-lived professional player in Sydney – that Fletcher says he picked up many of the philosophies and credos that have served him well in his business life.

First there was the importance of working as a team – “your team is your family, and your family is your team” – and never letting your team down. Middle child Melissa, earmarked from a young age to take over from her father in charge of the Fletcher empire, says that value of teamwork has been “instilled” since she was small.

Another favourite lesson was to take risks. “If there are opportunities you don’t take up, you miss out on the rewards; you have to take a risk” was one piece of sage rugby advice Fletcher has always stuck by. “Never follow the mob; you’ll go broke. I always like to do what others aren’t.”

Just how big Fletcher International Exports has grown and how far it has spread its tentacles since Fletcher quit formal schooling in 1961 is often hard to grasp. Staunchly keeping his business as a private company run by the family, with no outside investors, shareholders or high-paid chief executives, has kept the full extent of Fletcher’s business success and acumen out of the public spotlight.

While Fletcher has made the occasional Rich List, his wealth is usually grossly undervalued. The turnover and profits from his giant abattoirs and meat exports, as well as the scope of his agricultural commodity trading arm, are largely hidden from public view. As is the family’s true wealth.

“We never give figures out,” says Fletcher bluntly. “If I say I’m rich, I’m in trouble; if I say I’m broke, I’m in trouble. We’re just a humble private family.

“Private families can run businesses better than public companies. We run our own show. We put all the money we make back into the business so we can keep doing things better, and it’s the family that makes all the long-term decisions.

“Being a 100 per cent family-owned business is the thing – like (former Visy boss and Fletcher friend) Dick Pratt said on his death bed – I am most proud of; the bulk of the company is owned by just me and Gail.”

The short version of Fletcher’s self-made-man tale is that young Roger quit the poor family farm when just 18 to go off droving, first delivering other people’s sheep and then later buying and selling his own. He walked sheep all over Queensland following the stock routes, rain and grass. “They’re the biggest, cheapest farm in Australia,” he once said of his long paddock days. “And I wanted to see Australia.”

“They were tough times, trying to keep those sheep alive. But it taught me that in life, things can always be worse; keep walking and you will get through it,” says Fletcher.

Fletcher finally locked in a contract with a wholesale company to supply meat from 300 sheep a week. He would buy the stock from local farmers and have them killed in town abattoirs, from Toowoomba and Ipswich to Blayney, Gunnedah and Moree, in those days mostly run by the councils.

He gradually built up clients, gained an export licence and started trading lamb and sheep direct to his own overseas customers without the need for wholesalers or export brokers.

Eventually, frustrated at the inefficiency and incompetence of these unionised council meatworks and boning rooms, Fletcher took the leap and in 1987, at the age of 42, got a permit to build his own new hi-tech sheep export abattoir in the central NSW town of Dubbo, a greenfield site with no history of a unionised workforce. And so FIE took off.

But embedded within that tale is a second backstory that quietly embraces some of Australia’s racial past.

While out droving, Fletcher used to have to find a red public phone box so he could call Moree to arrange to sell his sheep or to book into the abattoir. The telephonist at the exchange who patched through his regular calls was a young 18-year-old Aboriginal girl, Gail, who he happily chatted away to, often the only person he’d spoken to for days.

The pair fell in love, with their eldest daughter Pamela born a year later in Moree in 1969. But, in the 1960s Moree was a racially divided town, with the local Aboriginal population barred from the town swimming pool – until the Freedom Riders bus loaded with student activists in 1965 drew national attention to the ban – and many pubs and schools informally segregated. Fletcher’s family did not initially approve of the union. The couple lived in a garage behind a friend’s house.

Daughter Melissa, a proud Aboriginal woman and rural leader, says it is hard to appreciate now what a big step – and how socially unacceptable – the couple getting together was.

“It was a massive thing in those days; Moree was a tough town racially and Mum and Dad faced a lot of adversity. But at the end of the day Dad loved Mum and he didn’t care what other people said or how people judged them.”

Melissa says her parents’ 50-plus years together is testament to their partnership. Gail has always done the accounts, finances and bookwork, been pivotal in starting and growing the successful business and owns FIE in partnership with Roger.

Friend and local federal politician Mark Coulton says he is always surprised how little Gail’s pivotal role in the family business is publicly appreciated. “Everyone talks about the legend that is Roger, but Gail is just so smart,” says Coulton. “He’s the ideas man but it is Gail who is across the finances and detail, and who makes those ideas happen.”

In recognition of his family’s heritage and in a conscious decision to assist, there are more than 165 indigenous employees at the Dubbo Fletcher meatworks, 20 per cent of the 800-strong workforce, along with 30 other nationalities. Most are from Aboriginal communities across northwest NSW – Walgett, Moree, Brewarrina and Bourke – as well as Dubbo.

Many are young people who have come straight to Fletcher’s from juvenile training centres, while others have been in trouble with drugs and alcohol. The Dubbo meatworks was the first employer in Australia to become a Registered Training Organisation, able to provide quality training and nationally accredited qualifications.

“It’s a challenge but I am very proud of the diversity in our workplace and the tolerance,” says Melissa. “We still have a business to run (there are mandatory workplace drug tests), but my parents have always been kind and compassionate people who believe that if you can change one out of 10 lives for the better, you have achieved something good.”

Dubbo remains firmly home to the powerful businessman, who is as passionate about building up regional Australia as he is at wanting to see more bureaucrats and politicians in Canberra who have had some experience living and working in the bush.

Fletcher’s lifetime of business credibility has also enabled him to pick up the phone to everyone from Prime Ministers and ruling sheiks to Australia’s richest businessmen and biggest farmers. They often call him for advice too. “I do my share (of calling to Canberra),” he admits, “but only when there is a problem and I have a solution.”

Recent Fletcher ear blasts have included the ongoing problem with the docks and wharfie strikes, threatening the delivery of key shipments of grain, meat and cotton, and the lack of foreign backpacker and seasonal worker labour in this coronavirus-disrupted year. FIE currently has 150 jobs it cannot fill.

But Fletcher’s ascent to these lofty realms of power and influence has never been about attaining either money or fame. Roger and Gail Fletcher continue to live relatively simply on their small farm, Yarrandale, on the outskirts of Dubbo, next door to the now-dwarfed meatworks they daringly built on a dream and a prayer – and not much cash – 30 years ago.

Fletcher is not showy with his wealth, has no stunning harbourfront house in Sydney or private Whitsunday island retreat, and eschews private jets.

However, one particularly colourful story lingers from the ’90s when the late media magnate Kerry Packer picked Fletcher and his teenage daughter up in his Learjet to fly them to Packer’s floundering Rockhampton abattoir, in the hope of fixing its terminal problems.

The trip ended with a mightily impressed Packer inviting Fletcher to become his partner – and Fletcher refusing, saying his only business partner would ever be Gail. Packer then offered 18-year-old Melissa a job saving his Queensland abattoir. At that point Roger reportedly said his daughter was not available as she was off to run FIE’s own new meatworks in WA.

According to his family, Fletcher completely lacks hobbies, other than breeding better sheep on his family-owned farms. “He always dreamt of being Australia’s biggest sheep farmer from when he was a boy,” teases Melissa. “It’s his real love; (son) Farron’s got the bug too.”

“The Boss” still works 10-hour days in the business, although Melissa is now in charge of day-to-day operations. Oldest daughter Pamela is involved in the WA sheep and lamb empire.

Fletcher’s rare days “off” are usually spent driving five hours to visit his sheep farms near the outback NSW mining town of Lightning Ridge, or the family’s showpiece irrigated cropping and sheep property, Kiargathur, near Condobolin, where Farron lives and runs the agricultural side of the family firm.

Or he might be found quietly judging lambs at the Glen Innes agricultural show, near where it all began. Or back at his old alma mater, Farrer High, buying White Suffolk rams bred by its agricultural students, many of whom wind up with summer holiday jobs at Fletcher’s in Dubbo.

Travelling the world meeting with loyal customers who are the lynchpin to the success of his meat business, who can’t get enough of his diverse high-end chilled lamb products sold in boxes all simply stamped with his famed “Fletcher Dubbo” brand, remains a priority. So too does sitting as a director of the Australia Meat Industry Council.

“But nothing is about status with Dad,” says Melissa. “He’s just driven by the challenge of looking for continual improvement, and ways to do things smarter. “Sometimes I think he sees life like one big game of Monopoly; all about chance, luck and the guts to roll the dice. You win some, you lose some, but you have got to play to win.”

Fletcher is even more succinct. “You make your own life. There’s always challenges. But the main thing when you have a problem late at night is to train yourself to go to bed. Life is always better in the morning.”

JUST A SIMPLE FARMER

With all the focus on Roger Fletcher’s massive sheep and lamb processing business, just how big a landholder and farmer he is often escapes attention.

Fletcher is happy to keep it that way; when interviewed he is always remarkably cagey about the full extent of his farming operations, which his son Farron Fletcher, 42, now runs. “Oh, we’ve probably got about 250,000 acres (100,000 hectares) all up,” he says casually, before changing the subject.

Fletcher has always owned and traded sheep, from his earliest days as a young drover in the 1960s. Even after building and opening his family’s greenfield Dubbo abattoir in 1988, he kept his own large sheep mobs that were agisted across northern NSW, primarily as an insurance policy to keep throughput of lambs at his meatworks up in times of short supply so Fletcher could always meet the orders of long-term customers overseas.

In 2001, Fletcher bought the first of seven farms encompassing more than 40,0000 hectares that the family now owns between Lightning Ridge and across the Queensland border towards Dirranbandi.

“(Dad) had been in that country in his previous life as a drover, and knew the area, and its potential for a sheep breeding enterprise,” Farron Fletcher told a local Dubbo newspaper in May. “We’re in a seasonal game and it’s important to have consistent, reliable supply 52 weeks of the year.”

The next property purchased was a showstopper, attracting the sort of national attention Fletcher likes to avoid. In 2005 the family bought prized 32,000-hectare Kiargathur Station on the Lachlan River near Condobolin, from the Kidman family, in a $33 million deal. Fletcher has since developed the iconic property, where Farron and his family now live, into a mixed farming showpiece. Cotton is grown, as well as irrigated lucerne for hay and silage, and vast grain crops. A lamb feedlot has been added to speed up prime lamb production, augmenting Kiargathur’s bountiful Merino grazing country with its flock of 22,000 breeding ewes.

In May 2016 Roger Fletcher shot into the national spotlight by emerging as the holder of a 20 per cent stake in controversial Cubbie Station, Australia’s largest cotton and irrigation farm near Dirranbandi. Fletcher bought his stake from the global Lempriere wool business, which had been forced to sell its one-fifth share in Cubbie to an Australian-only investor under Foreign Investment Review Board rules, before itself being absorbed into Chinese textile conglomerate Shandong Ruyi, the other 80 per cent owner of Cubbie Station. Fletcher finally offloaded his stake in Cubbie in 2019 when Macquarie Agriculture swooped and bought 49 per cent of the irrigation giant, including Fletcher’s portion.

Meanwhile Fletcher had also sold – and then permanently leased back – more than 10,000 hectares of his prized Kiargathur Station to a group of Sydney investors for $13 million, freeing up capital to help part-fund his Cubbie involvement and also develop his new lamb feedlot at Condobolin.

“There are a lot of (farm ownership) models out there at the moment and I don’t think it hurts to have a mix,” Fletcher told the Australian Financial Review.

Roger Fletcher says while shoring up lamb supply for his Dubbo meatworks is part of his reason for buying farms across northern and western NSW, it is not the whole rationale. He says his own lamb production is minor in scale to his two abattoirs, keeping them busy for the equivalent of just a week’s kill (90,000 lambs) in total.

Staying in touch with the land, the seasons and what the farmers who supply him with lambs are going through is another motivation for Fletcher’s farming ambitions. But so too is the long-term financial security of his family an imperative for the former drover.

“(Owning land) is an opportunity to give us some back-up in tough times,” says multi-millionaire Fletcher, in a telling moment.

“I’ve got an abattoir and meat business but if suddenly there were no sheep (available to slaughter) tomorrow, what would I do with it; it wouldn’t be worth anything. But if you own your own farm, the land is always worth money because it can be turned into sheep, cattle or wheat; you’re never going to be completely broke again.”

MORE AGJOURNAL

WHO OWNS AUSTRALIA’S FOOD AND FIBRE SUPPLY CHAIN