How cotton growers could solve Australia’s clothing waste problem

A Goondiwindi cotton trailblazer is diverting clothing waste from landfill by spreading it on paddocks. He says it offers big benefits to growers.

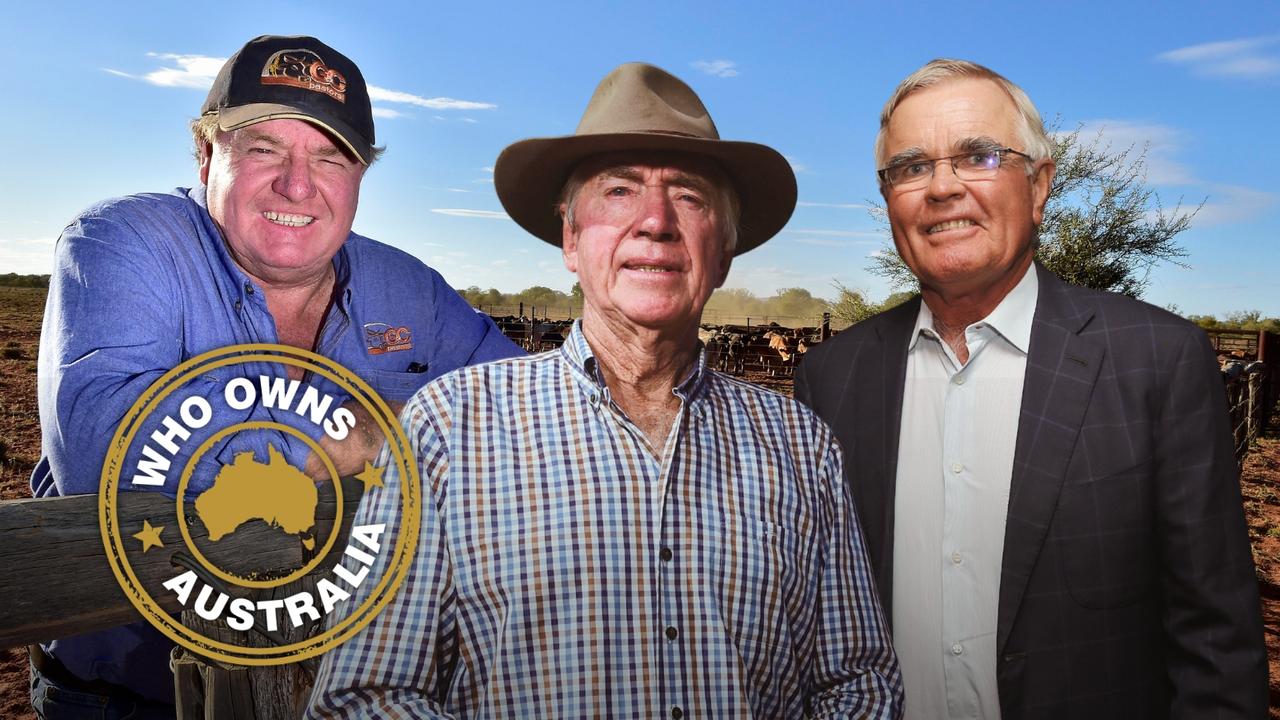

Sam Coulton is not one to throw things away.

The third-generation Queensland cotton grower keeps everything that still has potential use on his Goondiwindi farm. He says he inherited the trait from his father, Keith, a pioneer of irrigated farming in northern NSW who was honoured with an MBE in 1979 for services to agriculture and passed away earlier this year.

“You know, bits of the Model-T Ford, old crank handles; he never threw it out,” says the 70-year-old. “The gene comes through.”

Coulton is hardwired, then, to solve one of the textile industry’s biggest problems: waste.

Australians produce a lot of it, discarding an average 23kg of clothing per person each year.

“It’s always annoyed me, rubbish,” Coulton says. “I’ve always thought if you are going to produce something, you should be responsible for getting rid of it.

“When I found out the numbers of clothes that go back into landfill, you know almost 800,000 tonnes of garments (a year) … that’s a serious amount.”

Speaking from his office on Alcheringa, the 1000-hectare irrigated property just south of the Queensland-NSW border that is the flagship of his family’s cotton, crops and cattle enterprise, Coulton explains he has been investigating ways to return used cotton garments to the soil for years. It’s an idea he started toying with after founding his own cotton clothing brand, Goondiwindi Cotton, in 1989.

Today, he is a driving force behind a groundbreaking cotton circularity project funded by Cotton Research and Development Corporation aiming to divert clothing waste from landfill by shredding it and spreading it on growers’ paddocks pre-sowing.

Once incorporated into the soil, the material will break down quickly without releasing copious amounts of methane as it would in landfill, and hopefully provide environmental and economic benefits to growers.

“To have that ending of being able to grow it then put it back into the soil, you feel good,” Coulton says. “It’s completion of the whole circle.”

ADDICTED TO FAST FASHION

Research from the Australian Fashion Council shows Aussies tossed 780,000 tonnes of textiles on the rubbish heap in 2018-19, with clothing making up about 32 per cent.

The federal government put clothing textiles on its Product Stewardship Priority List in 2021, and tasked the AFC with developing an action plan. This year AFC launched a voluntary scheme called “Seamless”, with a goal of designing all waste out of the clothing supply chain by 2030.

Coulton and the other supporters of the CRDC circularity project say the cotton industry can lead this charge.

Launched in 2019, the project’s partners include Cotton Australia, the Queensland government, linen brand Sheridan, circular economy advisory Coreo, CRDC-supported scientist Dr Oliver Knox and Coulton’s Goondiwindi Cotton.

The R&D body will invest $2 million in the project over the next three years to reach a scalable phase, matched by in-kind and cash investments by partners.

CRDC research and development manager Dr Meredith Conaty says the project aims to “capitalise on the natural properties of cotton to try to create a co-win for everyone to help deal with the problem that we all know is there, that we’re in a linear supply chain”.

“Growers are our levy payers and we invest in research for their good, so what we’re trying to do is fill in the gaps behind Sam while he really has the vision for trying to make it happen on his farm and then in his business,” Conaty says.

Goondiwindi Cotton has so far invested more than $50,000 in bringing the project to life, covering on-farm expenses, transport of the material to Alcheringa and spreading costs.

Soil scientist Knox says having a grower-partner as committed as Coulton is integral to making the project work.

“It’s one of the wonderful things about the Australian farmer community. I think they are prepared to do the extra bit, even if it’s a bit of a cost to them, if it makes a difference to the way in which we manage our land and how our land will be handed on to the next generation,” he says.

“Sam is great for embracing things like that.”

Ploughing fabric into farmland is not a novel idea, Knox says. “Historically, how did we get rid of our clothing? We threw it out with the muck and it went off and was put on farmers’ fields because it was all cotton or it was all wool or it was all leather and it broke down.”

What is new, however, is that Knox now has scientific tools to measure the benefits.

RESULTS SO FAR

Alcheringa is the main site for the circularity project field trials, now in year three.

Coulton has just finished spreading 10 tonnes of shredded cotton, supplied by Sheridan, across two plots – one 700-metre run of 36 rows and a second 700-metre run across 12 rows – before sowing his 2023-24 crop.

In the first two years, 2.3 tonnes was spread, stopping the equivalent of 2.07 tonnes of carbon dioxide from being pumped into the atmosphere (as the cotton material would have if decomposing in landfill) while improving microbial activity in Alcheringa’s soil.

Knox tracks everything from soil nutrients, microbiology and carbon levels to how plants’ branches develop, fruit position, fruit retention and maturation time as part of the trial. He says preliminary results show a boost to soil carbon in the top 10cm and an increase in sulphur – a sign of soil fertility and health.

Importantly, the shredded garments have done no harm, which was one of Coulton’s main concerns. The pair worked on lab experiments for 18 months to minimise the risk of contamination from fabric dyes before embarking on field trials. “It was really nice to be able to say there is no damage to the crop, establishment was great, there was no additional disease, no loss of yields,” Knox says. “No impediment in the farming system for doing this. I feel confident that if we see it as a long-term practice that it will add eventually to the stability in the structure and improvement of our soils.”

WATER-SAVING POTENTIAL

Cotton Australia supply chain consultant Brooke Summers says the first year of field trials confirmed the project “is a goer”.

“These paddocks are taking tonnes and tonnes of textile waste on a tiny amount of our cotton land,” she says. “That was the big microphone-drop moment for me.

“The first spreading of about two tonnes went just 200 metres up one paddock, then it was gone in three months. The scalability part is pretty incredible.”

Coulton spread at a rate of two to three tonnes a hectare this year. Australia’s national cotton crop size fluctuates, but in 2022 more than 448,000 hectares were planted, showing the potential to divert waste is huge. But questions remain about what’s in it for growers.

Beyond the “feel-good” factor, Coulton says water-efficiency gains show promise. “What we saw in the first year, it was only a patch three times bigger than this room, was that (the paddock) was much wetter all the time,” he says. “Because cotton holds 90 per cent of its weight in water. Until the microbes eat it, it’s holding it. One of our main problems in farming – the No.1 problem – is moisture.”

Aussie cotton growers are some of the most water-efficient in the world, using an average 0.8 megalitres to produce a bale in 2022.

That amount has been decreasing for the past 25 years, averaging 0.93 megalitres over the period – less than half the global average of 2.07 megalitres, according to NSW Department of Primary Industries.

Yet industry is struggling with momentum, and isn’t hitting its target of 2.5 per cent water efficiency gains a year as growers get closer to what is physiologically possible for the plant.

“If we can grow better crops with less moisture, they (growers) would definitely jump on board,” Coulton says.

Knox is adding soil moisture probes to Alcheringa this year, hoping the numbers stack up.

The scientist also sees big potential in job creation in rural communities. “The thing that excites me quite a lot is we have this urban waste issue and we have a rural opportunity to basically reconvert it into something that could be used in agricultural settings,” Knox says. “If we can move what is currently a waste reprocessing industry to a rural community we might actually help provide jobs and income.”

CRDC is funding research into how to best collect and shred waste textiles, with hopes cotton gins could be used for some of the process.

Coulton says the project has generated a lot of interest from carbon project managers, but he’s “not chasing carbon”.

“We’ve had the carbon money like an ants trail from here to Brisbane. It’s been unbelievable,” he says. “As soon as they drive here and when I say (results) haven’t shown me signs of much carbon (increase) yet, they all make their way back to Brisbane. There is plenty of money in carbon but there’s none on the recycling side. And that’s the main aim of this game – to put the product back into the ground.”

CHECK THE LABEL

The patenting of polyester in 1941 has made today’s quest for cotton circularity a more difficult endeavour.

Synthetic fabrics, including polyester and nylon, account for about 62 per cent of clothing sales in Australia, while cellulosic fibres, primarily cotton, account for just 38 per cent. This has swung from 20 years ago when two thirds of clothing sold in Australia was cotton.

Petroleum-based easy-care polyester doesn’t biodegrade like natural fibres do, and has a supply chain that is a one-way route to landfill.

Cotton grower Sam Coulton and Cotton Australia supply chain manager Brooke Summers say manufacturers such as circularity project partner Sheridan have a major role to play in cutting waste by choosing natural fibres for their product ranges.

“We want brands to do two things,” Summers explains. “One is use 100 per cent cotton in their products and see natural fibres as a critical part of their circularity strategies. And two, design with the end in mind.”

Sheridan innovation and product general manager Joanna Ross says the brand takes its responsibility to design out waste seriously, and is proud to support a collaborative approach that spreads responsibility and benefits along the entire supply chain.

“Product sustainability and process optimisation is a part of our day-to-day and we are passionate about circularity and finding end-of-life solutions for our products,” she says, explaining the brand designs products for a long life, and cotton is often naturally the best yarn choice.

Sheridan has a take-back program at all of its stores, where customers can return used bedding and towels from any brand.

Since launching in 2019, they’ve collected more than 105 tonnes to divert textile waste from landfill.

Coulton’s Goondiwindi Cotton offers a similar recycling service called Farm Fill, giving customers a 10 per cent discount if they send old garments back to the farmer-run business.

Coulton’s aim is to eventually shred these garments as part of a scaled-up version of the current trial on Alcheringa.

WORK TO DO

There are still many problems to iron out.

Summers says they must find ways to tackle blended fibres and remove things such as buttons, zippers and tags from clothing to make the project scalable.

“We know for sure we don’t want synthetic fibres in our farming systems,” she says.

Technology is developing so quickly, Coulton says robots with artificial intelligence could be a viable solution in the near future for dismantling garments.

Conaty says finding an economical way to shred and transport the material is another big issue.

“Just moving the textile waste around is by far the most expensive part of the whole operation,” she says.

Costs to bring the two tonnes of the fluffy stuff to Coulton’s farm blew out to $10,000 a tonne in the first year.

“We couldn’t compact it – it came up in big bags,” he says.

“Then Sheridan sent me some. They had shredded it nowhere as near as fine as (the first year), then they compacted it. And it was only $50 a tonne.”

When the thicker compacted material arrived on Alcheringa, Coulton had to change the machine he used to spread it. But he says the trial and error is worth it, because success could be transformational for his community.

“Irrigation underwrites Goondiwindi, and Moree, and Narrabri,” he says. “When the droughts come people get put off farms and they move out and it hurts the businesses down the street. It happens all the time.”

Coulton says the irrigated agriculture industry feels a responsibility to power the rural economy – “We have to have that consistency and quality of product coming through” – and he’s confident the circularity project can help even the boom-and-bust cycle caused by droughts and flooding rains.

Meanwhile, he’s getting on with the job at hand, and just needs more waste to spread, and more partners to help.

“I need people walking through and saying, ‘listen I can give you X amount of product. When do you want it and where do you want it?’,” he says. “Come and join the team. Get on board. Help me – that’s what I need.”