How Melbourne was earmarked for Russian invasion

When Melburnians woke to a sensational headline claiming Russia was planning to invade, it was the start of a tense relationship built on suspicion.

Victoria

Don't miss out on the headlines from Victoria. Followed categories will be added to My News.

In March 1882 Australians all around the colony woke to a sensational headline that chilled their veins: Russia was making plans to invade Melbourne.

It was the result of more than three decades of tension with the British Empire that had seen the Russian navy puff its chest from the Pacific to the Antarctic.

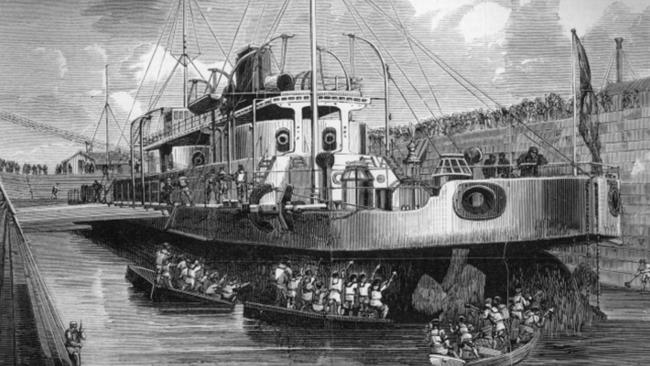

The colonial Victorian defenders, inhabiting a city just decades old, were forced to shape up their fortifications and build state-of-the-art ships and weaponry to stave off the threat.

But with accusations of espionage and subterfuge, the Russian Empire’s true plans for Melbourne, a wealthy boom town drenched with gold, remained clouded.

‘Friendly visitors’

Concern about a Russian attack on Melbourne began in 1854 with the passage of Russian warships through the Pacific.

The Crimean War of the 1850s had colonial Australia on heightened alert for a sneak attack by the Russians.

Fears were revived in 1863 when the Russian warship Bogatyr made a friendly visit to Melbourne and a press article suggested a raid was imminent.

The story claimed a Polish man living in Melbourne had a nephew on Bogatyr who warned him that Russia, led by Tsar Alexander II, was planning to attack.

The veracity of the claim was never proven.

But anxiety around a Russian invasion spurred the colony to improve its fledgling fortifications, including the fort at Queenscliff, built in the 1860s.

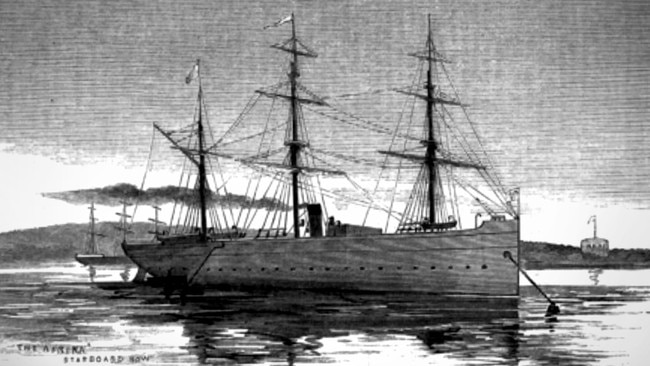

The rivalry bubbled for two decades and came to a head in 1882 with a formal visit by a squadron of Russian warships to Australia, headed by the flagship Afrika, at a time when the shadow of war was again hanging over Britain and Russia.

The Russians entered Port Phillip Bay in January, made a formal salute by firing their cannons and a Victorian ship returned the honour.

The foreign admiral and officers were received well on shore and crews from the Victorian and Russian ships took part in a series of friendly boat races.

By this time the Russian Tsar was Alexander III, whose keenness to play nicely with the Australian colonies was viewed by some as an outright threat.

Suspicion heightened with reports that Admiral Aslanbegoff had knocked back a series of formal invitations to dine at the prestigious clubs in Melbourne, and stayed at the Menzies Hotel instead of as a guest of the Government.

Soon the Melbourne press was awash with fear that the Russian visitors were effectively casing the joint.

The cold accusation was later put in an Australian newspaper: “Admiral Aslanbegoff could not bring himself to hobnob with the leading men of the city he intended at no distant date to loot.

“It would be a kind of desecration first to drink their champagne and then imbue his hands in their blood, so the admiral determined to refrain from the usual felicities.”

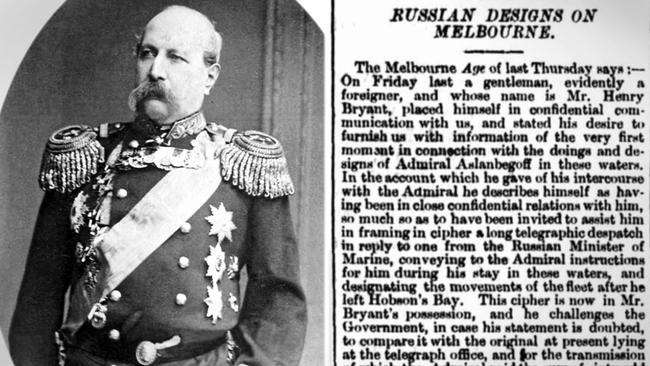

Fear of the Russians reached fever pitch in February with the publication in Melbourne of an explosive dispatch supposedly sent secretly by Admiral Aslanbegoff to the Russian Tsar.

It detailed the nature and flaws of Melbourne’s defences, and the strengths and weaknesses of its naval fleet, including its most powerful gun ship Cerberus.

About a week later the Russians left Melbourne but speculation about their planned invasion continued.

In March, a Queensland newspaper editorialised that Melbourne was the Russians’ preferred point of invasion “when the inevitable declaration of war between Great Britain and Russia takes place”.

It claimed Melbourne was rich after the gold rush and while Sydney’s forts might put up a stiff fight, Port Phillip Bay “could be shelled and brought to surrender easily in 24 hours by such a fleet as that commanded by Admiral Aslanbegoff”.

The colonial government immediately splashed money on bigger guns for forts including Queenscliff and organised a standing corps of a few hundred man to defend the colony.

Fears of a Russian invasion of Melbourne flared again in March 1882 with another explosive news story, this time claiming that war was imminent and that a huge Russian fleet multiple times bigger than Aslanbegoff’s was waiting in the ocean to smash Melbourne and loot it for five million pounds.

The information had come from a mysterious ‘Major Bryant’, who proved to be a hoaxer.

Reluctant allies

Tension with the Russian Empire continued for years and anxiety about an invasion remained prominent in public discourse.

In 1886 outspoken Victorian MP John Woods, who had made it his aim to study and thwart Russian strategy in Australia, claimed to possess documents that blew the lid on the Tsar’s movements in the colony.

Woods, who was praised for his uncanny ability to pre-empt the moods and actions of the Russian Tsar, was due to lay bare in parliament the full Russian designs for Australia, which might have included economic or military action.

But at the last moment another MP named Gillies moved that Woods be made chair of the session in the absence of the regular chairman.

As a result he was gagged.

Melbourne’s Punch newspaper decried the move as scandalous, accusing Gillies of being on the payroll of the Russian Tsar.

In the end the mysterious dossier remained closed.

By the early 20th Century Australia and Russia were allied in WWI, and even after the deposition of the Russian royal family in 1917 and the rise of Bolshevism, would be allied again in WWII.

Anxiety about the Russian threat returned during the Cold War, and perhaps the edge of suspicion has never left.

Australia now, as in the 1880s, readies its defences for whatever might come.

More Coverage

Originally published as How Melbourne was earmarked for Russian invasion