Grotesque tale of one of Victoria’s worst killers

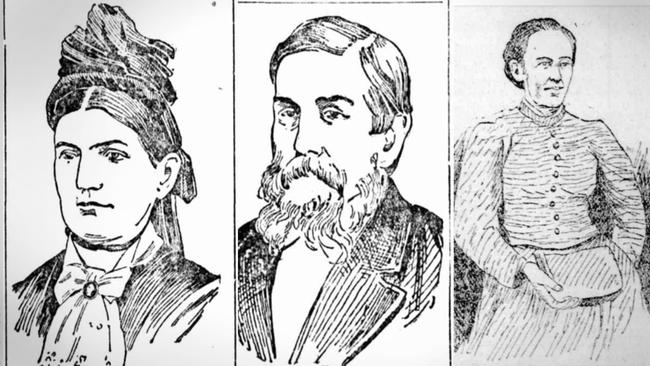

Henry Lyfield brutally killed his wife at their home near Port Fairy but an investigation later exposed an even darker secret on the family farm.

Victoria

Don't miss out on the headlines from Victoria. Followed categories will be added to My News.

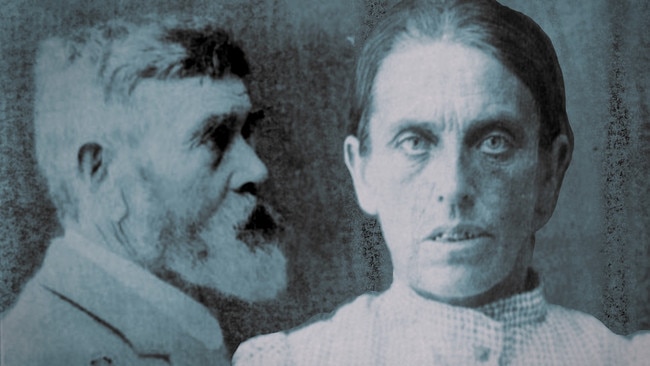

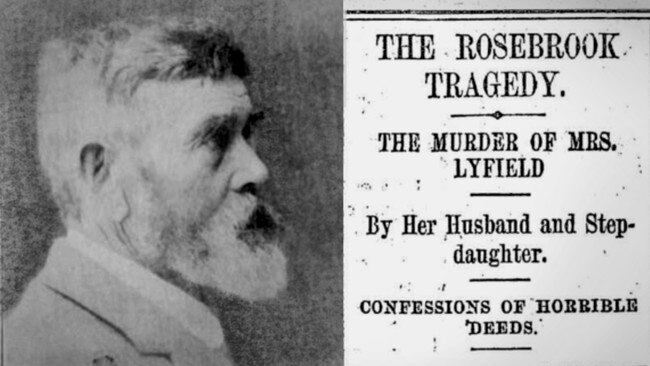

When Henry Lyfield, a dairy farmer from Rosebrook near Port Fairy, was charged with the brutal murder of his wife in 1896, police had no idea how bad the story would get.

Not only did Lyfield kill his wife in cold blood, ditching her battered body in a river, but the investigation revealed he might have been one of Victoria’s most grotesque serial killers.

And the little dairy farm at Rosebrook held the darkest family secrets imaginable.

The poor widower

Maybe Henry Lyfield was just unlucky in love.

In October 1896 the 66-year-old rode into Warrnambool from his dairy farm a few miles away, telling all and sundry how his wife had got up and left.

Poor thing. This was the second wife he’d lost.

His first wife had died years earlier, leaving him with several children, and he had since remarried the young and vivacious Catherine, a domestic servant.

But it seemed Catherine had finally had enough of Henry Lyfield’s eccentric personality and sometimes uncontrollable temper.

Now Henry was on his lonesome, tending the farm with the help of two of his daughters and his 13-year-old granddaughter.

Perhaps there were a few whispers around town about what had really happened to Catherine.

But there was no evidence anything untoward had transpired.

Until one morning when a lad named Robert Russell hauled a dray of milk over a bridge on the Merri River near Warrnambool and saw something strange in the water.

When he arrived at a factory to make his delivery, he told the workers he thought he’d seen a body in the creek.

Nobody believed him, except one worker who visited the river out of curiosity.

There he saw a pair of human legs poking out of a sack.

The alarm was raised and police used a boat to pull the body of poor Catherine Lyfield from the water.

She had been strangled by a long cord that still hung around her neck, her arms were tied up around her head and the sack in which she was fastened barely made it down to her knees.

Her head had been badly slashed and beaten, and her body was in a state of decomposition.

But it didn’t take long to identify her.

In the bottom of the bag, clinging to the victim’s hair, was a discarded letter that bore the name Lyfield.

It was a name one of the police constables remembered.

He had met a man named Lyfield in Warrnambool the previous day; a man who had been complaining about how his wife had run off.

He had even been inquiring around town about a housekeeper.

The police put two and two together.

The body was found at 8am, and by 10pm Henry Lyfield was in police custody, facing a murder charge.

Dark secrets

Lyfield denied any connection to the murder of his wife.

But when police brought in his two daughters and his granddaughter, a sordid picture of the killing emerged.

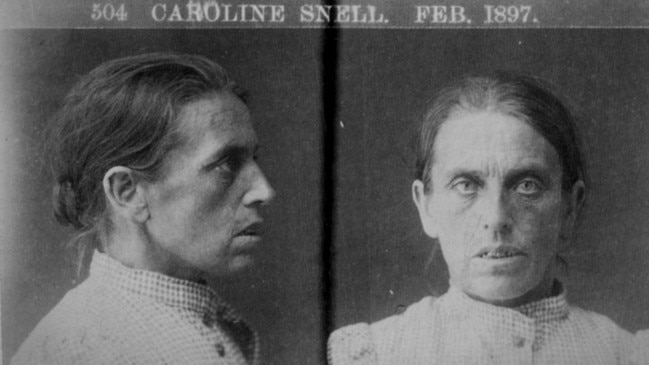

The youngest of Lyfield’s daughters, Caroline Snell, was living in the farmhouse with her teenage daughter after her own husband, a former farm hand, had left her.

She described an extraordinary tension that built between Henry Lyfield and his second wife Catherine over a number of months.

Catherine seemed anxious to keep an eye in everyone in the house, especially Caroline and her daughter.

She fought loudly and frequently with Henry until one evening when an big argument in the couple’s bedroom fell oddly silent.

After a while, Henry gave some of Catherine’s clothes to his daughters, telling them to dispose of them and claiming Catherine had gone away and wouldn’t be coming back.

The women knew something was badly wrong.

In the evening they heard Henry Lyfield dragging something heavy through the back door and later they saw the body, bundled in a sack and covered in hay, in the back shed.

Old Henry flew into a rage at the suggestion he’d killed Catherine and threatened all sorts of things unless the women kept quiet.

Then he lumped the body on a cart and set out towards the river, and that was that.

Or so Caroline Snell said.

But as the weeks went on, and police dug deeper, an even more disturbing picture emerged.

Even darker secrets

After weeks of holding back, Caroline Snell, who police described as illiterate with a childlike mind, unloaded her heavy conscience on police.

And the tale was truly shocking.

After the death of his first wife, Henry Lyfield carried on an immoral sexual relationship with his daughter Caroline for years.

She had fallen pregnant multiple times, and claimed that Lyfield killed the young babies and buried their remains somewhere on the farm.

During one of the pregnancies, Lyfield had offered a farm hand named Snell a portion of land if he agreed to marry Caroline and raise the child.

At first Snell agreed, but after a while he tired of the arrangement and ran off.

That left Lyfield with his daughters – one of whom was also his granddaughter.

Then there was poor Catherine.

She was just 19 when she married the widowed Lyfield and must have soon known things were not right.

Her suspicions grew about his relations with his daughter and now, sickeningly, his granddaughter.

She tried to keep an eye on all of them, becoming haunted and paranoid, until she discovered the awful truth, leading to her demise.

It was found that Caroline Snell, far from an innocent witness, was in the room when Lyfield murdered his wife by strangulation.

In reply to the new horrible evidence, Henry Lyfield tried to spin a tale that made his killing of Catherine seem justified.

The accusations he made against his dead wife were so graphic and disturbing that the judge ordered women and youths to leave the courtroom before they were read out.

Newspapers refused to print the delusions, which were held up as proof that Lyfield was insane and unfit to stand trial.

Eventually both Henry Lyfield and Caroline Snell were declared not guilty due to insanity.

Snell was admitted to the Benevolent Asylum in Melbourne where she resided for the rest of her life.

The claim that Henry Lyfield had murdered his babies and buried them on his property persisted, although no remains were found and Lyfield himself never confessed.

The family estate was taken over by a special administrator and Lyfield was lodged in Melbourne Gaol indefinitely while the system tried to fathom his fate.

Given light labour, his health deteriorated and less than five years after arriving at the jail he died of heart and lung failure at the age of 71.

His death made headlines as the whole sordid affair was once again inked in newspapers across the country.

As one editor observed: “Even the beasts of the field have a superior sense of decency to that possessed by some creatures belonging to the human species”.

“We have said that for the sake of humanity a feeling of relief is generally experienced when the perpetrators of particularly loathsome crimes can be truthfully pronounced insane, but there was so much hideous sensuality and cool calculating brutality in Lyfield’s behaviour that it seems a thousand pities that anything should have intervened to save him from the gallows.”

More Coverage

Originally published as Grotesque tale of one of Victoria’s worst killers