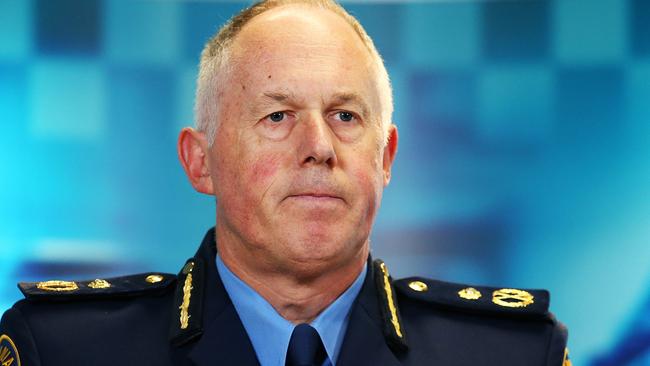

A former Tasmanian top cop has opened up on the notorious cases that kept him awake at night, his inspiration behind joining the force and how policing evolved over his four-decade career, Sam Stolz writes

Scott Tilyard is treading frigid water wearing yellow, household-issue dishwashing gloves.

He is searching for human remains.

A man has gone over Launceston’s Cataract Gorge into the river. Tilyard is on what he thinks is a missing persons case.

He shows this reporter a small, jagged scar running down his thumb. “The dishwashing gloves didn’t offer the best protection against the sharp wire protruding from the murky water,” he laughs.

The body is eventually found. Someone stumbles across some bones and clothing on the eastern side of the River Tamar. It turns out to be a homicide – the man was pushed over the Gorge during an altercation. Case closed.

In Tilyard’s 41 years as a Tasmania Police officer – with 10 years as Deputy Commissioner before retiring in 2021 to take up chair role for the state’s Road Safety Advisory Council – he has seen it all.

The 60-year-old has encountered the sweetest – and the most rotten things – humanity can dish up.

From murders, rapes, bashings, drug raids, armed robberies, hostage situations, sieges, acts of family violence, fatal road crashes and even domestic terrorism – Tilyard has been on the front line. The thin blue one between order and chaos.

Many cases have kept him awake at night.

1989. Tilyard was working Launceston CIB. He was called to the rural Evandale property where a 15-year-old boy had taken his dad’s shotgun and blasted both his parents and 10-year-old brother to oblivion.

His reason for committing the crime – “his parents wouldn’t let him go to the swimming pool,” Tilyard says.

“That case really stuck with me. It was a split-second decision where he killed his entire family, destroying their lives and his own.

“His dad was still in the bed, his mum on the kitchen floor and his younger brother was near the back sliding door that he was trying to escape through. A tragedy all around.”

In 2004, the man was released from prison, paroled until 2017. He cannot be identified because he was a juvenile when he committed the crimes.

While still a police cadet at the age of 18, Tilyard saw his first dead body during a mortuary admission. It was an infant who died of what was then referred to as SIDS.

“I had never seen a dead person prior to that. It was a terrible thing. But dealing with death is part of what police do, and you know that going in. But there are some things you look back on – and it does have an effect,” he says.

Tilyard was on duty the day of Port Arthur tragedy. He was watch sergeant at Glenorchy Police Station.

“The phone lines were blocked. It was obvious something was going down. We were told, by one of the assistant commissioners at the time, that basically every police officer on duty had to go down there (to Port Arthur),” Tilyard says.

“I was a member of the hostage negotiation unit at the time. It was something that you would think would never happen in a lovely place like Tasmania. The memorial to the victims has been done in a very respectful and discreet manner.

“If there was any good that came out of it, it was the changes to our national gun laws. And a huge credit to (former prime minister) John Howard for making that decision.”

He was on the Poppy Task Force in the 1980s, tasked with hunting down illegal crops or crop thefts where crooks would process the poppy into opiates.

Tilyard says armed robberies in the 1980s were “substantial” – meaning “it wasn’t the theft of your sandshoes or mobile phone – but more often than not credit unions and banks.”

“It was pre-ATM’s, pre CCTV. If someone wanted a serious amount of cash they would usually target a bank. It happened fairly regularly,” he says.

Tilyard recalls an armed robbery at a Riverside bank, in the West Tamar.

“One of our detectives had some information on a prolific crook from Victoria who was apparently living in the area who matched a witness description,” he says.

“Sure enough, we raided the property and up in the roof there was a bag with $20,000 in cash and a gun.”

Tilyard says the gun was a dead giveaway.

“A witness at the bank gave a fairly accurate description, saying the weapon ‘looked like a pirate’s gun’,” he says.

“It was actually a sawn-off .22, with leatherwork and bullets nailed down the side. So yeah – it did kind of look like a pirate gun,” Tilyard laughs.

There was the time Tilyard was attending a multi-day siege at a remote farming property, trying to talk down a man taking potshots at police with a shotgun – while he was riding a tractor.

“Ultimately we had to get K-9 dogs over from the mainland during the very long negotiation process. Eventually the dogs came in and took him down.”

As the retired policeman talks with the Mercury, you can see that some of these cases won’t ever leave him.

The tough-looking bloke across the table is a far cry from the 17-year-old Tassie boy who once dreamt of not donning a badge, but becoming a graphic designer.

Tilyard grew up in Devonport and moved to Hobart in the late 1970s to complete his final years of high school at Elizabeth College.

The aspiring graphic designer who “was reasonably good at drawing” had a light bulb moment. Something deep in Tilyard’s soul hates bullying. He says, “it starts at school, seeing people being picked on who cannot defend themselves”.

“I think it is what underpinned joining an organisation where I could help prevent that behaviour in the community,” he says.

“I had a friend from high school who was training at the Rokeby academy. He gave me the tour one weekend and that was all I needed to know. I signed up for the Tasmanian Police Force – as it was known then. I had just turned 18 and it was 1981.”

Tilyard graduated in December 1982 and was posted to Launceston for constable general duties – the beat.

He was given the standard garb at the time. A heavy woollen overcoat “that weighed a tonne – not ideal for rolling around in the gutter locking up a drunk”, his hat, ceremonial tunic, badge – and a standard police issue .38 Smith & Wesson five-round revolver.

“It’s a far cry from the uniform today. Obviously the multipurpose vests now are stab resistant, bullet resistant. You can put plates in them to make them even more bullet resistant,” he says.

“The vests today carry a lot of extra gear that we did not have. All we were issued with was handcuffs, a short rubber baton, a dolphin torch and a gun.

“Back in those days we used to spend a lot of time on the beat. Some weeks you’d be rostered on nothing but the beat. Walking the streets all night.

“We also didn’t have computers. We had one that could check licenses registrations but even that was new. If we pulled someone over after business hours we had to contact the Watch Sergeant who would need to get the key to the Transport Commission. He’d drive down there, unlock their door, go in, check the old card system and then come back and tell us.

We still used typewriters. When we used to conduct interviews we would sit down with three or four sheets of carbon paper and you would type it all. If you were interviewing someone for a murder this would take hours and hours (laughs).”

When asked if the nature of crime has changed in Tasmania, Tilyard says it is largely the same.

“Police are still responding to the same types of crimes as they did 40 years ago,” he says.

“But the way police respond to those crimes have changed. Operationally the biggest change has been in the field of family and domestic violence.

“When I first joined, we responded to what were then called ‘domestics’. Back in those days most of the calls came from neighbours, not so much from victims themselves. Family violence was still in the shadows a lot.

“The general response in those days was to remove the offender – who was more often than not a male – and take him somewhere else for the night.

“And that was it. There would be no paperwork. No charges. Obviously in extreme cases there would be charges.”

Tilyard says domestic violence prosecution in his years as an officer had “come a long way” and it was an advancement he was most proud of seeing.

“Fortunately, victims of family violence now have a lot more confidence in the system, are prepared to come forward and know that they will be properly supported,” he says.

Tilyard says two horrifying family violence-related murders – one at Longford and one at Launceston – “made police and government realise more needed to be done”.

“Every jurisdiction in Australia has had very, very nasty family violence-related murders, murder-suicides.

“The statistics that are often stated is that one woman loses her life to family violence every week in Australia. Unfortunately, I think that is still the case. But there is no doubt that the changes that are being made to support family violence victims, including children, and to bring to justice the offenders has saved the lives of many people.

“There’s more that can be done – but there is a lot that has been done.”

For those considering a career in policing, Tilyard imparts some advice.

“It’s still a great career and it is still my view that Tasmania Police is the best and most trusted police service in the country. It’s a career with 100 different jobs. No two days are ever the same.”

Ultimate guide to what’s on in Tassie this summer

Summer is coming! Make the most of the warmer weather with our go-to summer events guide – it’s packed with must-do Tassie activities to enliven your social calendar and kickstart 2026 in style

Gus Leighton – on sax – brings Tassie party vibes to the max

Whether he’s firing up a dancefloor, improvising in a jazz quartet or swinging kettlebells like a pro, Tasmanian saxophonist and gym-enthusiast Gus Leighton loves being the life of the party.