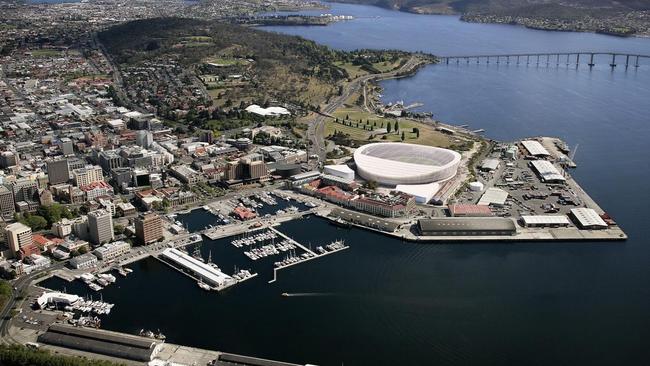

Simon Bevilacqua has revealed what he really makes of the mixed-use stadium at Hobart’s Macquarie Point, saying the project is part of a much bigger cultural vision than we all realise.

A Hobart AFL stadium has the potential to be a potent cultural totem for Tasmania.

I write this article to plead with stadium opponents to reconsider, and to beg the proponents to

ensure such an arena is but one aspect of a much bigger cultural vision.

I can imagine a project that unites disparate aspects of Tasmania in a multipurpose cultural precinct encompassing Hunter Street, The School of Creative Arts, the TSO Concert Hall, The Hedberg, Macquarie Point stadium, The Cenotaph, Queens Domain and a Truth and Reconciliation Art Park.

This diverse cultural hub brings people together – a meeting place.

Such a precinct, with a brave architectural design at its core, could not only deliver economic spin- offs but become a priceless investment in community wellbeing.

Tasmanians have felt the transformative power of David Walsh’s MONA. It changed the way people see Tasmania and how Tasmanians see themselves. Let’s run with that audacious spirit.

The most deep-rooted, widespread cultural pursuit on the island is Aussie Rules. It has been the glue of communities and the touch stone of family life across the island for generations.

However, it is so integral to the Tasmanian way of life, it is taken for granted. We can’t see wood for trees. Go to Portugal, Malaysia or Holland and you won’t find ovals with four posts at each end.

Tasmanians have for generations gathered at such ovals on winter weekends. Fathers played footy, sons played and now daughters do too. Husbands and wives met and broke up at club functions.

Lives, loves, tragedies and triumphs have all played out against a backdrop of this unique game. Aboriginal activist Michael Mansell played footy. Former premier Peter Gutwein played too, as did former premier Ray Groom and former Liberal leader Bob Cheek. In fact, in the ‘70s and ‘80s, it was difficult to be elected in Tasmania if you had not played.

Aussie Rules is thought to be rooted in indigenous culture. There are colonial reports of Victorian Aborigines playing a game where clans fought over a possum-skin ball. I can’t find such references in Tasmanian records, but the game is unequivocally integral to island folklore.

Two of Tasmania’s most celebrated writers, poet Pete Hay and journalist Martin Flanagan, have long portrayed the game as a cultural phenomenon in celebratory yarns about saveloys, scoreboards, car horns and boot studs. Their stories reveal the extraordinary in the ordinary.

Take for example Hay’s ripper yarn about Wynyard taking on North Hobart in the ‘67 state final.

Wynyard was ahead a few points, but a disputed mark meant North was awarded a free kick at goal to win the game after the siren. Wynyard fans rioted and stole a goalpost. The kick was never taken.

“This game was clan footy at its proudest - pulsating, passionate, committed, riveting - and it ended without a result,” Hay wrote in his essay halftime with Stout John.

Footy legend abounds, especially from the halcyon days of the 1950s to the 1970s, when it produced VFL champions like triple Brownlow medallist Ian Stewart, Saint skipper Darrel Baldock and the greatest goalkicker the game has seen, Peter Hudson. This era has a mythical status similar to the thylacine, and some fear that, like the famous tiger, its days are over.

After working in all three regions of the island over more than 30 years in journalism, I can confirm that footy is struggling. The tough economic times of the ‘80s and ‘90s steamrolled once-proud clubs and the ruin has continued the past 20 years with a lack of vision from the AFL.

Anti Macquarie Point stadium rally organisers demand Premier Rockliff call election

A few weeks back, however, I went to the footy at Dodges Ferry, 30 minutes’ drive from Hobart. The Sharks oval, a stomping ground of Collingwood high-flyer Jeremy Howe, was packed with cars and cheering fans of all ages.

Former premier Gutwein told me he observed similar community spirit the week before when he drove his family from Launceston to Scottsdale to watch his 16-year-old son, Finn, play for Bracknell seniors. “The ground was full of cars,” Gutwein said. “It’s a real family atmosphere.”

The game’s grassroots are alive. “Footy just needs a focus, and that’s what a Tasmanian club will deliver,” Gutwein told me.

Some blame the AFL for ruining the game. There is no doubt that as the big league has grown rich, country competitions have fallen into disarray. But the idea that the AFL held the state government to ransom over the stadium is an overreach. The way I understand it, and this came from the horse’s mouth, Gutwein, when premier, decided on a stadium with a retractable roof in late-2021 because it would ensure the venue would be a multipurpose cultural centre. It was his idea.

The reason was that international acts, such as British singer-songwriter Ed Sheeran, like to start tours in a small city to ensure lights and audio work, stage scaffolding can be setup and packed away, and the performance is ready. Two legendary shows by Dire Straits at KGV Oval at Glenorchy in 1986, with over 20,000 at each, were examples of this.

However, to lure international acts to Tasmania, Gutwein said the government had to insure shows against being washed out and the cost was exorbitant. Thus, when he publicly announced a stadium with a retractable roof in February, 2022, it was based on his desire for it to be a multipurpose, all-weather venue, not just for AFL.

“The AFL did not pressure me,” Gutwein told me, saying the league warmed to his idea of a state-of-the-art stadium packed with parochial Tasmanians providing gripping TV viewing. “Remember with each broadcast, images of Hobart, the mountain, the bridge and the river, from the stadium will be beamed nationwide. It’s priceless advertising.”

It was at Gutwein’s 2022 announcement the ballpark figure of $750 million was raised. Opponents suggest the “real” cost will double that. Such a blowout would not surprise anyone who has renovated or built a home recently. Material and labour costs are rising with inflation.

I spoke with stadium opponent Richard Flanagan about all this and he asked how Tasmanians could, in good conscience, spend such a vast sum on a stadium when there are homeless people living in tents on the Domain. It’s a challenging ethical conundrum.

‘Bloody gutful’: Lambie’s message to Rockliff over stadium

“The whole stadium thing is a house of cards,” the Booker Prize-winning author told me. “The costings are a lie, 60pc of Tasmanians don’t want it, and there will be growing outrage as Tasmanians have to pay for it with closed hospital beds.”

Flanagan’s view is alarming, but let’s suspend the horror for a moment.

When I started reporting on Tasmania’s health system in the late 1980s, I learnt that the health portfolio was a poisoned chalice because it did not matter what a health minister did, the opposition thrived on the department’s bad news and pounced on the political fallout.

Over five decades Labor, Liberal, Liberal-Green and Labor-Green state governments have failed to fix the system, despite pledging earnestly to do so.

I spent years talking with medical specialists and clinical administrators about how to fix the system only to find that no one agreed on the remedy. The complexity of a two-tiered public and private system, funded by individuals, Medicare, private insurance, and state and federal governments is mind boggling. The same procedure in the same hospital bed by the same specialist can cost different amounts depending on who pays and how a claim is administered.

Add to the mix the constant advances in care that are expected by all; an ageing population; competition between hospitals and communities for resources; nationwide GP, nurse and specialist shortages; bald-faced profiteering by unscrupulous medicos; IT redesigns; decrepit buildings designed and built last century; and myriad other issues, and there is a prima facie case that a solution is beyond any one state government and that talk of “fixing health” is spurious politics.

More than a third of Tasmania’s entire state budget already goes to health. On average, a startling $7.3 million is spent every day delivering health services (Tasmanian State Budget 2022-23).

At $750 million, a stadium with a retractable roof equates to the cost of running health services for about four months. With the feds injecting $240 million, the cost to Tasmania is two to three months’ health services, and about six months if you think the cost will blow out to $1.5 billion.

After years reporting, I also learnt that helping people who live in tents is not always as simple as providing a house. Many, not all, who sleep rough have complex health issues such as alcohol addiction, drug use, sex abuse, family breakdown, a history and culture of intergenerational poverty, and diagnosed and undiagnosed mental conditions. These are cold, hard facts.

A roof over the head may be a start for some, and we must push on with affordable housing, but even with extra support others fall through the cracks. It is tragic. We live in a world where alcohol, crystal meth, cannabis and new synthetic drugs are rife. The state used to lock people in asylums and jails, but modern wisdom suggests we not criminalise or punish these behaviours, but treat them as health issues. As such, the day there are no people sleeping in tents will be of biblical significance.

Sometimes the answer is not an either/or decision, we have to do both. That means working on long-term solutions to complex health issues and housing, as well as short term ones.

Sydney Harbour Bridge was built in the Great Depression when unemployment surged and many Aussies lugged swags in search of jobs, but the bridge has since benefited generations, not just in crossing the harbour, but as a global symbol of who we are as a nation.

The critical question is whether the long-term financial and symbolic value of an iconic cultural precinct, with a $1.5 billion multipurpose, all-weather stadium for AFL and concerts, is worth as much to Tasmanians as we spend every six months delivering health services.

As for stadium costings being a “lie”, that’s rubbish because - and here is the rub - there are none.

I’m sure figures have been raised at meetings between the state, the AFL, the clubs and the feds, but at the time the Tasmanian AFL licence was announced I am convinced, after speaking to many behind the scenes, that little detail had been formally agreed.

Why? The project is yet to be designed let alone costed. All we have is a loose agreement that there is a pot of money on the table with an AFL licence. That certainty is expected to grease the wheels.

This may seem inept at first glance, but it is better than the alternative.

For decades Hydro Tasmania and Forestry Tasmania have dealt secretly with banks, departments, councils, the University of Tasmania, Treasury, the feds and private enterprise. They bypass ordinary Tasmanians and stitch up multi-billion-dollar deals before going public. Belated “consultation” is a sham. Think the $2.3 billion Basslink undersea cable, the $2 billion pulp mill proposal for the Tamar Valley and Marinus Link, valued at $3 billion based on 2021 forecasts.

The stadium deal is different. The ducks are not in a row. The project is a paper tiger.

Opponents have had a field day launching accusations and interpreting the muted silence in response as a “lack of transparency”, “secrecy” and “lies”. The tardy response, however, is better explained by the fact there is little of substance to reveal, which is, of course, fertile ground for opponents to sow fear.

Enter, stage left: Richard Flanagan, who M&M Communications media consultant Mark Thomas advises is vastly underestimated in Tasmanian politics.

“Richard Flanagan is easily the most powerful unelected politician on the island, and possibly the most powerful in the country,” said Thomas, a senior adviser in the former Bacon state government. “And he has powerful friends.”

Flanagan honed his media skills in the ‘80s and ‘90s protesting the Franklin River dam and the logging of old-growth forests. In the ‘00s he fought the Tamar Valley pulp mill and in recent years he has joined the fray against the University of Tasmania’s relocation into Hobart city and the island’s salmon farms, penning the book, Toxic, in 2021.

A Rhodes scholar and former University of Tasmania student president, Flanagan is a seasoned media performer and passionate public speaker. He can work the phones and is well connected, locally, nationally and globally. At the drop of a hat, he can call on a cast of thousands.

I have fundamentally agreed with most of Flanagan’s causes, but I worry the hostility of his polemic is unnecessarily divisive for an issue of such historic importance and cultural significance.

Flanagan called the stadium a “chimp enclosure”, a menacing metaphor the meaning of which is obscure but is hauntingly suggestive of some of the subhuman slurs that shame our colonial past.

He also described the Tasmanian Premier as “spineless and isolated” and portrayed the AFL’s licence negotiations as “arrogant bullying” (Mercury, April 21).

This wholesale demonisation of those with whom he disagrees was launched at a media conference to present an alternate vision for Macquarie Point, without a stadium, alongside a full bench of eminent supporters, including University of Tasmania Pro Vice Chancellor Aboriginal Leadership Greg Lehman, high-profile Hobart lawyer Roland Browne, and former Tasmanian governor Kate Warner.

Lehman worked with MONA creative director Leigh Carmichael on the original vision for a Truth and Reconciliation Art Park after MONA was appointed in 2015 to design public space in a masterplan to transform the 9.3ha site into a “dynamic, mixed-use precinct” (Mercury, December 14, 2016).

The Mercury ran front-page sketches of the plan, which included a long memorial walk on a jetty into the Derwent that featured Spectra-style searchlights and appeared to double as a ferry terminal (December 14, 2016). It was a grand design. However, the alternative vision put forward by Lehman, Flanagan, Browne, Warner and company looked very different from the original plans.

Lehman explained to me that the stadium footprint was too large to accommodate the original plan, and that only a “nature strip” of land had been set aside for it. “It struck me as tokenistic,” he said.

He also told me a Macquarie Point art park working party that no longer included MONA had not met for more than six months at the time of the licence announcement.

He said the Premier and Housing Minister had recently assured him they supported an art park and a stadium. Gutwein told me the same. Carmichael last week joined the chorus (Mercury, May 23).

So, is the art park “axed”, as Flanagan asserted (The Age, April 29, 2023) and, if so, who axed it?

Many who watched Dreamtime at the G or any of the indigenous performances during the past two weeks of the Sir Doug Nicholls AFL rounds, will agree there is no part of our society doing more to reconcile with, and respect, the ancient cultures of this land than the AFL. It’s been inspiring.

Some might argue in return that no part of society more urgently needs to change, with the AFL still dealing with the booing of Adam Goodes and racism allegations at Hawthorn and Collingwood, but that is precisely my point. The big league is championing the cause and challenging attitudes in the fray of the most widely practised cultural pursuit in the land. Aussie Rules is a cultural coalface of our society where meaningful change can happen - a place where eyes and hearts can be opened.

The AFL and clubs such as Essendon have appointed Aboriginal advisers and support systems. Similar advances are occurring with women’s football and the AFLW.

My father is thought to be the first Italian-born player to play in the VFL. He came to Australia as a boy with his peasant family just before the war and grew up in suburban Melbourne. With the swarthy skin of a southern Italian and a shock of dark hair and brown eyes, he was targeted.

Wogs, he told me, had to learn to use their fists in the backstreets of Carlton in the 1940s and 1950s.

When he began playing footy, his world changed. A nuggety rover with dash and a habit of running with the ball, Dad played a game for Carlton but spent most of his big-league days in the reserves.

Mum deplores footy, always has, probably because the first time she introduced Dad to her London- born migrant parents he had a black eye that had been stitched across his eyelid down his cheek.

Mum watched Dad play a few times, but found the rules incomprehensible - madmen chasing a leather ball for no good reason. She said when Dad touched the ball the fans in the grandstand leapt to their feet and roared. She didn’t know why, but he seemed to excite them.

Dad turns 90 next month, but only recently told me that the first time he felt accepted in Australia outside his Italian-speaking family was when he played footy. It was the reason he played. On the field, he was no longer an outsider. He was still a wog to some opponents, but he says they suffered the consequences of their abuse, not only from him but from his teammates.

Essendon’s Tiwi Islands champion Anthony McDonald-Tipungwuti reminds me of Dad. “Walla”, as he is known, is a better player, but he is short, powerful, fast, has skills on both sides of his body, and excites the crowd when he goes near the ball. When fans roar for Walla, I hear a song of redemption, a familiar tale of acceptance and transformation. The story resonates in many of the mellifluous names in the game, from Jesaulenko and Ishchenko to Chol, to Aliir, Ratugolea and Naitanui.

Yes, it is more than a game.

Surely, Tasmania has the ingenuity and goodwill to gather our cultural practices together in a precinct where disparate paths can intersect.

I imagine a meeting place rooted in deep history, which is acutely conscious of its heritage, but looks to the future to who we want to be as a people.

I imagine something like Sidney Nolan’s Snake from MONA winding into the precinct, through the stadium and out on to the memorial walkway into the Derwent, lined with art, and providing views of the bridge, the mountain and the river. I imagine a convention centre with seating for 4000.

I imagine ferries carrying passengers to and from MONA and from the Eastern Shore and Kingston.

I imagine a global attraction, famous for its architectural audacity and elegance, which provides unprecedented comfort for spectators and is integrated with state-of-the-art equipment for TV coverage of footy and concerts, ready for broadcast interstate and overseas.

I imagine a stadium with a retractable roof that provides smaller venues with outward views over the city to the mountain, the bridge and down river. I imagine fans marching from Sandy Bay, Battery Point, Sullivans Cove, the city, West Hobart, North Hobart, Glebe and The Cenotaph.

The project may cost $1.5 billion, but its benefits could be priceless.

Let’s not use this political football to bring down a state government, but instead come together to ensure it is something our grandchildren will be proud about and hit the federal government for a larger commitment, rather than the pittance it stretched across two electorates for political gain.

How many troubled children, seemingly destined to sleep rough, will cheer their local champions in a packed stadium and afterwards decide to go to the gym rather than smoke cones? How many will go all the way, average $400,000 a year in their AFL career, and buy a house by the sea?

Research by former attorney-general, the late Vanessa Goodwin, showed that most recidivists in Risdon Prison are from the same dozen or so Tasmanian families. Dr Goodwin’s post-doctoral research on intergenerational transfer of criminality showed family members felt trapped in a vicious cycle. This stadium and the opportunities provided by the AFL could help break that cycle.

Are there any big-bodied midfielders, drummers or singer-songwriters among the generation of Tasmanians we are asking to stop clear-felling our native forests? How many will go on to strum guitars to emulate heroes they see perform at the stadium? What sort of cross pollination of ideas could happen if disparate groups celebrate what they share rather than demonising each other?

At school on the North-West Coast many years ago, I saw a shy boy, three years my junior, play footy. His guernsey, buttoned to the collar, was two sizes too big and, despite its sleeves being rolled up, his hands were nowhere to be seen. His pins of legs struggled with muddy boots. The waif-like figure was from Penguin, a coastal town of 4000, many of whom live in the hinterland on dairy farms. The boy had talent, but was half the size of his opponents. He made up for it with enthusiasm and guile.

The boy left the coast a few years later to join the big league where he grew into a giant of a man.

His name is Brendon Gale, former Richmond ruckman, ex-AFL players association president and acclaimed chief executive of the Richmond Tigers, who has steered the club to three flags. He is one of the game’s most respected figures and was in the mix to become the next AFL CEO.

Watching him as a boy dashing about on a boggy wing on that grey North-West morning, a bitter squall whipping up sleet from Bass Strait, I didn’t see the bright future in store for Gale.

I don’t imagine he did at the time either but, at some point, he must have dared to dream.

Simon Bevilacqua has worked in Tasmania as a journalist for more than 30 years. Currently focused on a private writing project, he was recently approached by The Guardian to write about the Hobart stadium controversy, but the article he submitted was rejected for failing to fit the commissioning brief. This is a reworking of that piece.

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

Tasmanians embrace challenge as Point to Pinnacle turns 30

Once considered an event for the fittest and most serious athletes, Point to Pinnacle has evolved to capture wider public attention, inspiring ordinary Tasmanians to embrace an extraordinary challenge

Visionary couple revives Bothwell whisky estate

When Annie and John Ramsay bought the former Nant Distillery – now the beautifully restored Clyde Mill – they weren’t just bringing an old distilling site back to life ... they saw a chance to bring their community together