Before Charlie Read had even started high school, he was labelled a notorious child.

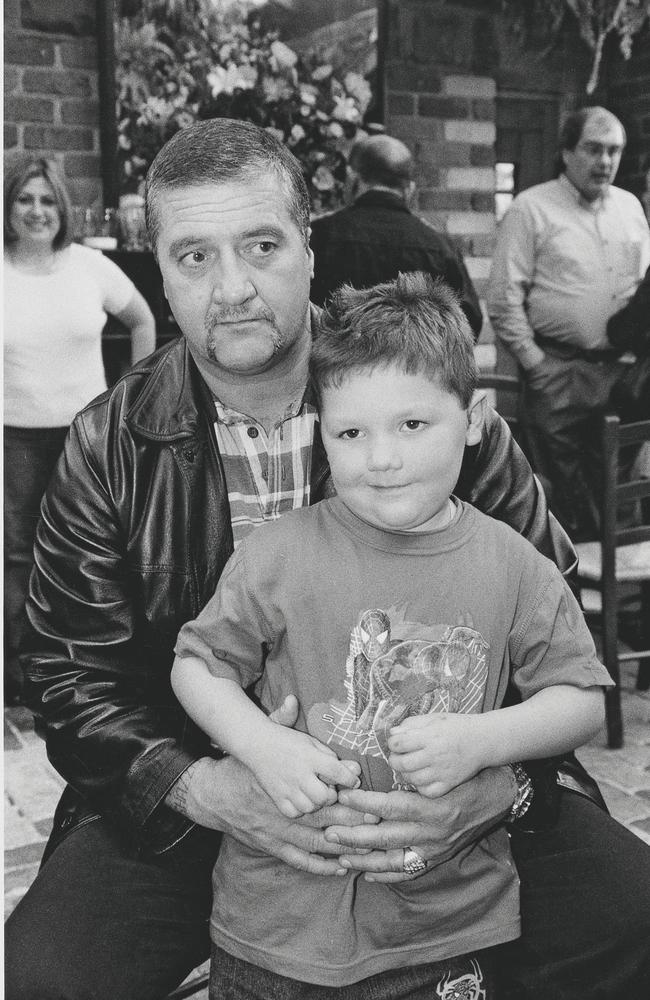

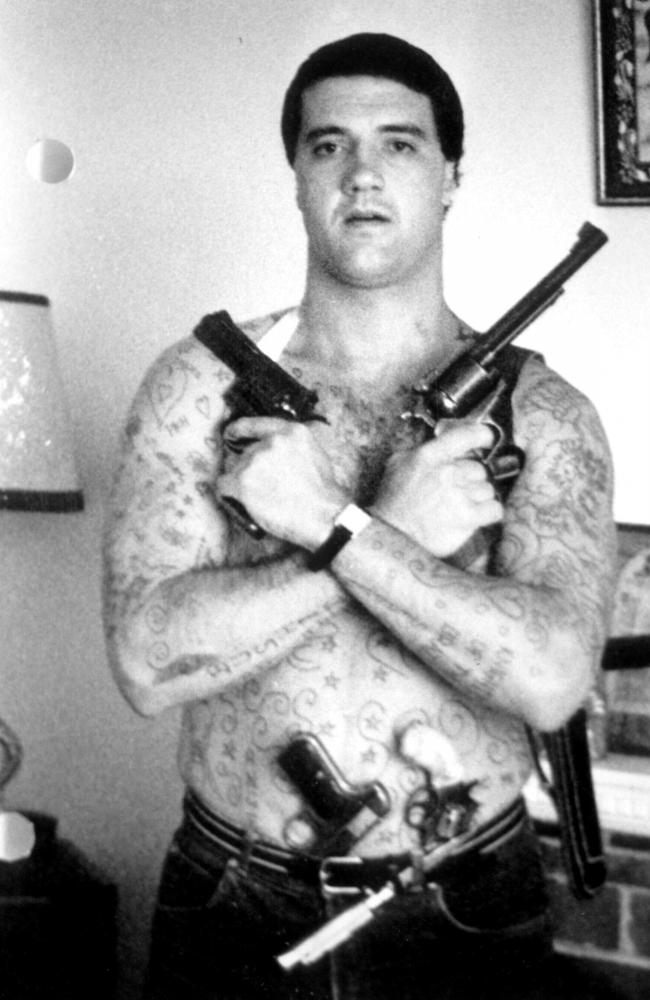

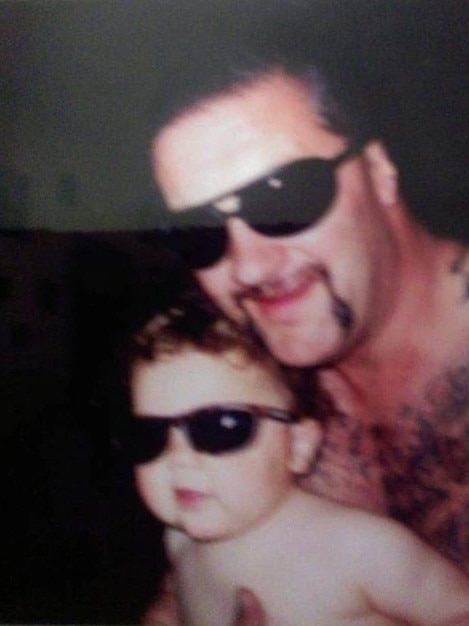

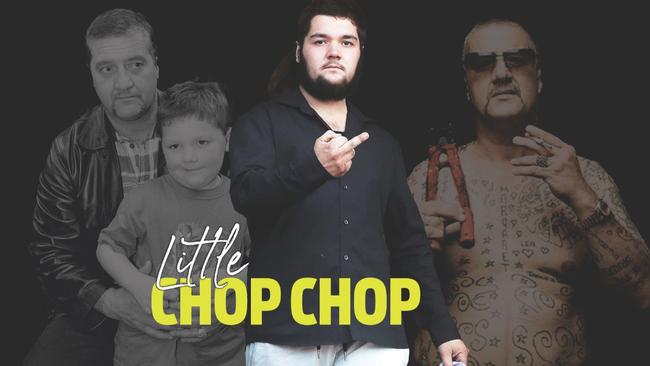

It didn’t help that his large frame, black hair and crooked smile were the spitting image of his dad; the infamous underworld figure Mark “Chopper” Read, who died in 2013 of cancer.

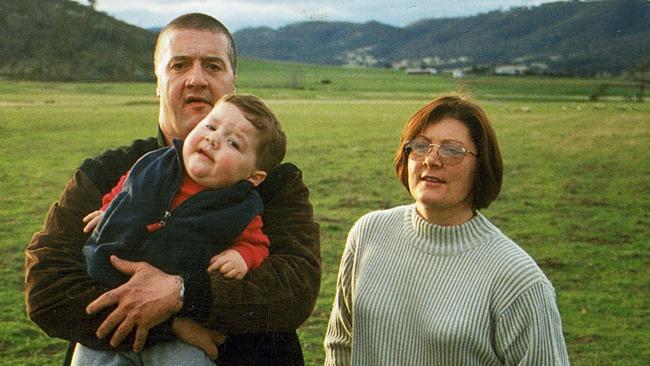

Charlie grew up torn between the violent, drug-soaked scenes of his father’s life in Melbourne, and the bucolic Tasmanian farms where his mother worked a steady professional job and enjoyed animals and the fresh air.

“I was treated like an adult. I shouldn’t have been,” Read said in court documents of his unusual childhood. “I’ve seen many things as a child that are hard to forget.”

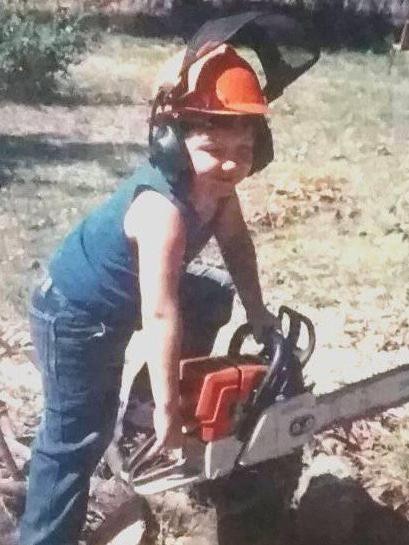

Before he’d reached kindergarten, Chopper had taught Charlie to fire a rifle, and the young boy worshipped his larger-than-life dad, despite not feeling comfortable in the lawless circles he moved.

“I was exposed to things a kid shouldn’t see,” Read said, including finding the dead body of a family friend who had overdosed, an experience he remains “haunted” by.

Last week in Tasmania’s Supreme Court the 25-year-old stared into the camera as he was sentenced to his longest stint in prison yet – one year and nine months – for a chaotic police chase in February last year.

It finally ended when Charlie was arrested hiding in a ditch, high on drugs, with two loaded, illegal rifles nearby. The charges associated with the midnight chase were extensive.

In the past few years, Read’s offending has escalated and snowballed.

His Hobart lawyer, Caroline Graves, worries that more serious crimes and a lifetime spent behind bars await him if something doesn’t change soon.

“Charlie is like so many young men who fall into a life of crime – disengaged from formal education, a trauma background. But he is at the pointy end,” Ms Graves said.

It’s a long way from the round-faced little boy who lived in a village outside of Hobart and wanted to be a farmer when he grew up.

Despite a social media presence full of hardman posing, leather biker vests and motorcycles, the portrait of the man to emerge in court this year has been far more nuanced, and complex.

While his friends may call him “Little Chop Chop”, his Mum – who he names as his closest relationship in life – still wants him to work in aged care, which she says he has a talent for.

And it was grief at the end of a 10-year romantic relationship that prompted the recent bout of offending, his lawyer told the court.

Love.

And drugs.

And history.

As Justice Robert Pearce sentenced Read last week – not without empathy – looming shadows could be seen in the edges of the prison camera, pawing at the window, seeking Read’s glance or acknowledgment.

“He was observed to be hero-worshipped by other prisoners who sought his attention as he tried to engage in the interview,” a psychologist wrote after meeting Read in prison earlier this year.

A bruise was visible on Read’s face on video link, not uncommon for his time in Risdon, where he has been subject to multiple stints in maximum security isolation after fighting with other inmates.

Read’s father was incarcerated in the same prison in the 1990s – and married his mother there, with his lawyer, Michael Hodgman, serving as best man.

“He gets provoked into fights, the attention just doesn’t stop and that’s the good, the bad and the ugly,” Ms Graves said of Read.

In his sentencing remarks, Justice Pearce acknowledged the hardship of growing up as the son of an infamous Australian criminal.

“I accept your father’s notoriety has been a problem for you but the time has come for you to be responsible for your own behaviour and get the therapy … recommended,” Justice Pearce said.

But those who know him best wonder if Charlie has what it takes to break away from his father’s out-size influence, which continues to shape his life with dark and uncanny force.

“This is a child who grew up with an infamous father,” Ms Graves said. “His life is becoming a self-fulfilling prophecy.”

Chip off the old block

Charles Vincent Read was born in 1999 in Hobart and is the product of a short marriage between his mother, Mary-Anne Hodge, who works in taxation, and Mark Read.

The split between Charlie’s parents in 2001 is described as amicable and they co-parented together. Charlie was just two when his father left Tasmania for Melbourne, where he married again and had a second son, Roy.

“Life in Tasmania was just too slow,” Mark Read said of his decision to leave the state.

“I couldn’t handle watching chickens and sheep running around day after day. I left with just the clothes on my back and enough money to get out of Tasmania.”

The relationship between father and son is described as “very loving” by Ms Graves, who has represented Charlie for a number of years.

“As Charlie has got older he has become more and more like this father,” Ms Graves said.

“He sounds like him, he looks a lot like him. His mannerisms and charisma and colloquialism and possibly sense of humour to the point of ridiculous in some of the ways he deals with police … trying to show-off.”

The two also share a healthy appreciation for “exaggeration”, Ms Graves says, with a laugh.

Despite the strength of their bond, Chopper’s “high-level criminal lifestyle”, as Judge Pearce put it, meant Charlie was exposed to significant trauma on his visits to see his father in Melbourne, including drug-taking and violence. In court documents, Read says he experiences “paranoia” which he feels he may have inherited from his father, has difficulty sleeping, and is “hyper-vigilant”.

In his sentencing, Justice Pearce said he recognised that Read suffered trauma and ongoing PTSD from his childhood, and self-medicated using drugs and alcohol – including heroin, methamphetamine, weed and MDMA – from a young age.

Read has said his latest stint in prison has been his longest period of sobriety since early adolescence, when an intense collision of events saw him expelled from school, his father die from cancer, and his infamy grow as curious adolescent boys discovered the phenomenon of Chopper.

Notoriety a curse

Among years with the Rebels motorcycle gang and a lengthening rap sheet, it can be overlooked that there have been periods of stability for Charlie.

He has worked felling trees, driving diggers and concreting, and had a steady 10-year romantic relationship from his mid teens, which ended last year.

In court documents his employers describe him as “industrious”, while Ms Graves says he is charismatic and quick-witted, just like his father.

“Like many of these young men behind bars, he needs an agent, not a barrister,” she said.

His mother would like him to work in aged care, saying in court documents that he is wonderful with older people, and had close, healthy relationships with his maternal grandmother and grandfather.

But that career path, along with many others, will likely be closed to Read, whose criminal record will bar him from a multitude of career paths.

“There are certain people that are attracted to him, such as outlaw motorcycle gangs,” Ms Graves told the Sunday Tasmanian.

“And they’re generally not the type of people who will keep you on the straight and narrow.”

Ms Graves says her client’s notoriety, lack of formal education and obstacles to gainful employment mean the risk of his reoffending and escalating his pattern of offending remain “very high”.

The recidivism rate in Tasmania sits at 50 per cent.

“Blaming the sins of the father is not going to solve the problem,” Ms Graves said, noting that she agrees with Justice Pearce who said it was time for Charlie to take responsibility for the direction his life was going.

“But because of his intelligence and sheer personality, I think he has the ability to transcend the current narrative.”

Ultimate guide to what’s on in Tassie this summer

Summer is coming! Make the most of the warmer weather with our go-to summer events guide – it’s packed with must-do Tassie activities to enliven your social calendar and kickstart 2026 in style

Gus Leighton – on sax – brings Tassie party vibes to the max

Whether he’s firing up a dancefloor, improvising in a jazz quartet or swinging kettlebells like a pro, Tasmanian saxophonist and gym-enthusiast Gus Leighton loves being the life of the party.