While working as a receptionist at a Hobart IVF clinic, Mollie D’Arcy came into contact with many Tasmanians who were struggling to conceive.

A naturally empathetic person, D’Arcy always wished that there was more she could do to help.

So when surrogacy became legal in Tasmania in 2012, D’Arcy started thinking about whether it was something she’d be able to do.

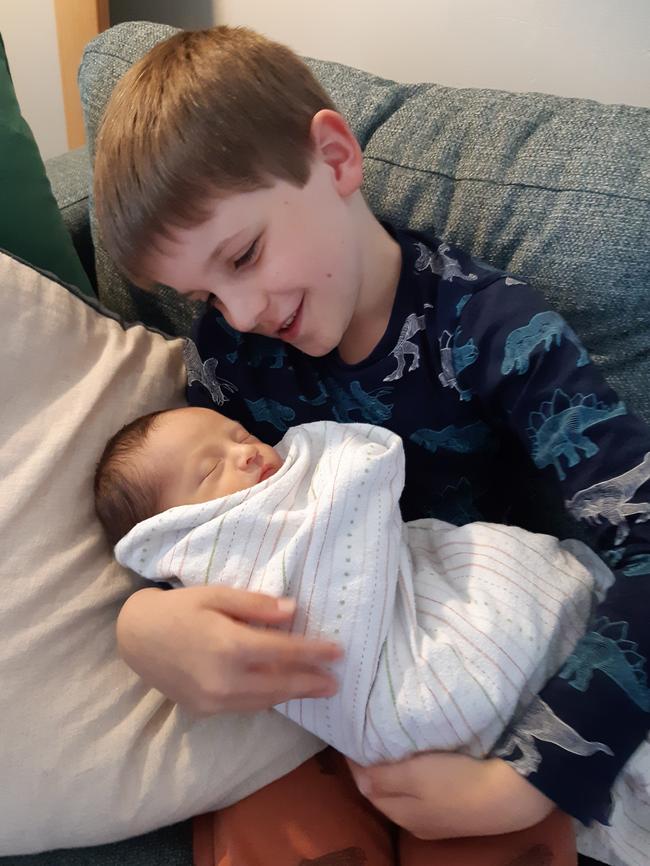

After having her first son, Finley, who is now 7, D’Arcy, who lives in Lenah Valley, was still thinking a lot about surrogacy. And while pregnant with her second son, Rowan, now 3, she spent lots of time in Facebook surrogacy groups, learning as much as she could about how surrogacy worked in Australia while chatting to other surrogates. D’Arcy then reached out to a Tasmanian same-sex couple – Daniel Gray-Barnett and his husband Daniel Barnett – forming a friendship that would eventually lead her to offer to carry a child for the men to help them achieve their dream of becoming parents.

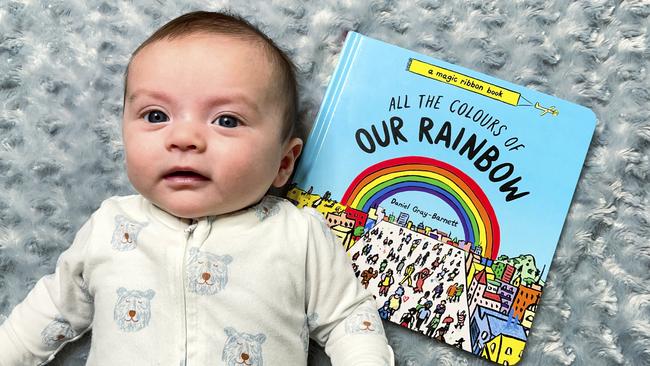

D’Arcy gave birth to baby Till Orlan Barnett at the end of February, a small but healthy 2.75kg (6lb 1oz) boy delivered at 38 weeks gestation.

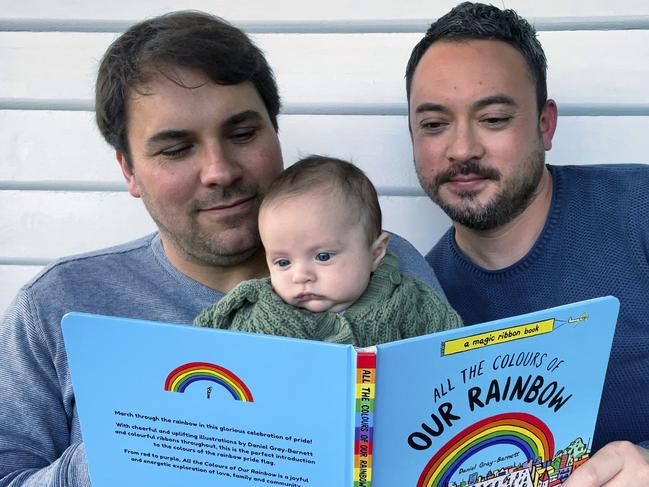

The Dans (as Gray-Barnett and Barnett are collectively known to family and friends) were “overwhelmed”, “thrilled” and “over the moon” to welcome Till to their family, while D’Arcy was delighted to be part of making their parenthood dream a reality.

And while handing over a baby that had been growing inside her for nine months might seem impossible to some, D’Arcy says it was “so worth it” and she’s already considering being a surrogate for a second time, with plans to carry another child for the couple.

The 38-year-old is also on a mission to raise awareness about surrogacy, as many Australians still don’t realise altruistic surrogacy is legal in Australia. Surrogacy is a form of assisted reproductive technology where a woman (the surrogate) offers to carry a baby through pregnancy on behalf of another person or couple, and then return that baby to the intended parents once it is born. About 100 surrogate babies are born in Australia each year, including a handful in Tasmania. It is estimated a further 300 babies are born to overseas surrogates each year for Australian parents.

D’Arcy would like to see greater support services for surrogates in Australia, as well as laws that are less confusing and less restrictive.

Australia’s first surrogacy baby, Alice Clarke, was born in 1986 – 36 years ago – although following her birth, many states introduced legislation to ban surrogacy, before later revising this legislation. As a result, altruistic surrogacy is now legal in all Australian states, although the rules differ between states – for example, in Tasmania a woman can act as a surrogate for intended parents in any Australian state, but intended parents from Tasmania who are searching for a surrogate can legally only use a surrogate from Tasmania.

Surrogates in Australia cannot be paid – although their medical expenses are paid by the intended parents.

The law prohibits paid advertisement for surrogates or the use of third-party recruiting services. And people who are wanting to become parents can’t legally ask somebody to be a surrogate for them – they instead have to share their story publicly and hope that a surrogate offers to help them.

The surrogate or intended parents can pull out of the agreement at any time. And the names of the intended parents aren’t initially included on the birth certificate at the time the baby is born, with legal proceedings required after the baby’s birth to make this change.

With so much uncertainty, it’s easy to see why some Australians might be reluctant to embark on a surrogacy journey.

But for Gray-Barnett and Barnett, surrogacy proved to be the best option and their journey with D’Arcy has been a smooth one.

Originally from Sydney, The Dans met 11 years ago and were one of the first couples in Australia to register their intent to marry when same-sex marriage became legal in Australia four years ago.

It was around this time they decided to move to Tasmania.

“Dan had been talking about moving out of Sydney and going somewhere else,’’ Gray-Barnett explains. “We came here on a holiday, to see if we’d like it as we’d never been (to Tasmania) before.

“We came to the Huon Valley and just loved it. Then we went back to Sydney and came back to Tasmania two weeks later and bought land at Franklin.’’

Within six months they were living in a rental property at Franklin. Their new home is expected to be completed in the next three months and they can’t wait to move in with baby Till and their two dogs.

Gray-Barnett, 40, works from home as a freelance illustrator – his clients include Disney/Pixar, Coachella Festival, Sydney Opera House, The New York Times, Warner Music and Penguin Random House. He has illustrated seven picture books for kids – including three he wrote himself. His first picture book, Grandma Z, won the Children’s Book Council Australia award for Best New Illustrator in 2019, and he has just released two new books – Katerina Cruikshanks and All the Colours of Our Rainbow. He also illustrated Zoe Foster Blake’s latest book, Scaredy Bath, which was released late last year.

Meanwhile Barnett, 43, works as a practice manager for a surgeon in Sydney – he was initially flying to Sydney regularly for work but since the coronavirus pandemic he has been able to work entirely from home.

He and Gray-Barnett also manage some local Airbnb properties and say they have “no regrets” about starting a new life in Tasmania.

They were keen to have children but knew it wouldn’t be an easy road.

“I always wanted to have kids,’’ says Barnett, who previously worked as a nanny in the UK. “And people – especially my three sisters – kept asking ‘when are you guys gonna have kids?’. “And I just said ‘it’s too hard, we can’t do it’.’’

They looked into fostering and also adoption but many countries still won’t adopt to same-sex couples. They also knew of people who hadn’t had very good experiences with adoption or fostering.

“After that, we decided surrogacy was our best option,’’ Barnett says.

But of course they first had to meet the right person to carry a child for them.

Gray-Barnett joined Facebook surrogacy groups to find out more about the process

and along the way he met D’Arcy. They chatted online before eventually meeting in person, at a local surrogacy group catch-up.

Despite there being other surrogates and intended parents at that meeting, Barnett and Gray-Barnett felt an instant connection with D’Arcy.

And D’Arcy felt the same way.

“It turned out I got along with them like a house on fire,’’ explains D’Arcy, whose second child was then about seven months old.

“It just seemed like we had a lot of similar interests. When I met them in person I just clicked with them, and I knew my husband would really like them.’’

They initially began chatting about work – D’Arcy’s role as a medical receptionist for Tasmanian obstetrics and gynaecology specialist clinic TasOGS had similarities to Barnett’s work for a medical specialist. But they soon realised they also had similar political views, and all three of them came from big families and were each one of five siblings.

“We were just aligned with so many things,’’ D’Arcy says.

They continued to catch up regularly and within a couple of months D’Arcy felt confident she could see a future as a surrogate with these men she now considered her good friends.

“I had already said to these guys ‘I reckon I could be your surrogate’,’’ D’Arcy recalls.

“Within a few months I knew I was going to help them, but I said ‘we’ll see how we go’. I was not wanting to rush into anything, I wanted to focus on building a friendship.

“And knowing I’d just had a baby I physically wasn’t going to be ready for a while, so I knew we had time to get to know each other.’’

She introduced the intended dads to her husband Rob, then later to her kids, and to her wider friendship circle.

As well as getting to know each other, there was also a lot to discuss when it came to surrogacy and all parties (including D’Arcy’s husband and young kids) were required to undergo counselling to ensure they understood the legal and emotional implications of the journey they were embarking on. They also had to consider what they would do if something was found to be seriously wrong with the baby in-utero, and be aware that any party could pull out of the arrangement at any time, leaving D’Arcy the legal guardian of the baby, despite it not being genetically related to her.

D’Arcy and her husband had to understand that they would be named as parents on the baby’s birth certificate, even though the child was not biologically theirs, with a parentage order created to legally make Barnett and Gray-Barnett the baby’s parents so an amended birth certificate could later be issued.

“They needed to make sure we had an understanding of what we were giving up and to determine that we were all of sound mind,’’ D’Arcy says.

Barnett says at no stage of the journey did he worry that D’Arcy would pull out of the agreement and not hand over the baby.

“I wasn’t ever worried about that,’’ Barnett says. “After knowing Mollie as long as we did, we got to know her friends and her family and we were just never worried. We knew if she wanted another baby she would have just had her own baby.’’

D’Arcy felt equally confident in her resolve to grow, and deliver, a healthy baby.

She says she became “fascinated” by surrogacy when it became legal in Tasmania in 2012 and when she had her first child her interest grew.

“After I had Finley I thought ‘I reckon I can do this for someone’, I just felt like I had the ability,’’ she says.

“I recognised how lucky I was and I really felt for all these patients (at Tas IVF, where she then worked) who had been trying for years to have a family.’’

She says she wouldn’t consider donating her own eggs to couples trying to conceive, but growing a baby, unrelated to her biologically (as it was created using a donor egg and Gray-Barnett’s sperm) was something she felt far more comfortable with.

“I couldn’t donate eggs,’’ D’Arcy explains. “I really wish I could do that but I just have such a focus on DNA when it comes to kids – how they look, who they are taking after … I just feel really connected with my DNA. “But as a gestational surrogate (carrying a baby created by a donor egg and sperm) I’m not related, it’s not my baby, I very much see this as looking after someone else’s child.’’

She enjoys being pregnant and says knowing she was going to be a surrogate in future meant she wasn’t sad going through her pregnancy with her second son, even though she knew her family would be complete after he arrived.

“I was really excited that it wasn’t going to be my last pregnancy,’’ she says.

Due to delays with Covid, she and The Dans were “more than ready” to finally proceed with the pregnancy in June last year.

The egg donor, a friend of Gray-Barnett’s, lives in Melbourne but the embryo transfer to D’Arcy was done at a clinic in Sydney, and she fell pregnant on the first attempt.

The pregnancy itself ran pretty smoothly, although D’Arcy did have a scare at 14 weeks when she started bleeding heavily and feared she could be miscarrying. However, all was well with the baby, which they found out was a boy at a 16-week scan and nicknamed him Tiny Dan.

Pregnancy symptoms were similar to D’Arcy’s previous two pregnancies, although due to the different blood types of D’Arcy and the baby’s biological parents she needed to have regular anti-D injections.

She had two emergency Caesarean sections with her own children so opted for an elective C-section at Hobart Private for Tiny Dan.

There were initially concerns about whether the baby’s two dads would be able to attend the birth, and whether they would be allowed to stay in the hospital with D’Arcy and the baby, as all hospitals have different policies regarding surrogates, with rules extra complicated due to Covid protocols. Typically, babies are expected to stay with their surrogate at all times.

However, D’Arcy fought to have the rules changed at Hobart Private – and Healthscope hospitals nationally – to better accommodate surrogates and intended parents. Barnett and Gray-Barnett were able to pay for an additional room next to D’Arcy’s and the baby was able to spend lots of time with his dads while D’Arcy recovered from surgery.

Both Barnett and Gray-Barnett were allowed to be with D’Arcy from the time she was admitted to hospital and they were both in the operating theatre to witness their son being born.

Gray-Barnett admits he was “really nervous” when the time came for the baby to be delivered and it was all “a bit surreal and overwhelming”. But he and Barnett were “over the moon” to finally meet their much-desired son.

“Mollie did an amazing job, what a wonder woman,’’ Gray-Barnett said when announcing the birth to family and friends on Facebook.

The name Till is German and means “people’s ruler” but it also comes from Tillman (someone who works the land) and Tillerman (the person who steers the boat) and Tilden (meaning fertile valley). The baby’s middle name, Orlan, is Spanish and means “renowned in the land”.

Gray-Barnett first saw the name Till in a book and despite having a long list of other names short-listed, the couple felt Till was the only name that suited their newborn.

D’Arcy stayed in an Airbnb adjacent to Barnett and Gray-Barnett’s Franklin home after the birth, along with her husband, kids and her husband’s mum.

She expressed milk for Till for the first couple of months to help boost his immunity. “It was really fun, I really enjoyed it,’’ D’Arcy says of those weeks post-birth.

“It was hard on my kids, and it was hard on Rob. Rowan is a needy three-year-old and he’s very attached to me.’’

She says for about a month she was “quite absent, emotionally’’ as her desire was to prioritise Till and make sure the new dads were well settled with their new addition. This was especially hard when D’Arcy and her kids contracted Covid when Till was only a few weeks old. But slowly she has settled back into her everyday life.

“In the hospital I was on a real high,’’ D’Arcy says. “I had a great birth experience, unlike my others which were unexpected, emergency C-sections. I was feeling really satisfied and was just focused on what I had to do. I was enjoying having a connection to (The Dans and Till), and feeling useful.’

“I’d spent nine months doing this thing for someone else and been focused on that thing. But the end goal is for another family. It was great and I felt as I expected I would, Till never felt like my baby.’’

She says some people might “hand over a surrogate baby and walk away” but she would never have been able to do that, which is why she chose a family that would be happy to have her included in their child’s life in some way.

She will be known as Aunty Mollie, while Till’s biological mother will be known as Tia, which means Aunty in Spanish.

D’Arcy’s own children adore Till and she hopes her boys will “grow up with a real understanding of altruism through this experience’’. And she’s already considering carrying a second child for the couple, with plans to be pregnant at the end of next year, this time using a donor egg and Barnett’s sperm.

“Straight away I thought I want to do this again,’’ D’Arcy says. “I always look forward to seeing baby Till and these guys. It’s really lovely to be taken back to various memories of my kids, and have baby cuddles. But it’s also great to hand him over to his dads for all the rest.

“I love seeing how bleary-eyed, dazed and confused they are every day. I feel very lucky that we’ve all been able to achieve this together.’’

Surrogacy Australia support manager for surrogates and intended parents, Anna McKie, says the journey of D’Arcy and The Dans is “wonderful” for Tasmania, as the state has only a handful of surrogacy births each year.

She says interest in surrogacy has grown steadily in recent years, but the number of hopeful parents far outweighs the number of surrogates – fewer than one in five couples seeking a surrogate will find one in Australia.

Surrogacy Australia, a not-for-profit organisation, was created in 2010 to advocate on behalf of families using surrogacy.

McKie estimates there are about 100 surrogacy births in Australia each year, although exact figures aren’t known. About 65-80 per cent of surrogates and intended parents are known to each other before embarking on a surrogacy journey together. The majority are gestational surrogates, where the surrogate’s egg is not used in conception, while traditional surrogacy, where the surrogate uses her own egg, is far less common.

A surrogate must be at least 25 years old in most states (18 in the ACT) and have previously been pregnant and given birth to a live child.

And only certain people qualify to use a surrogate in Australia – including women born without a uterus, those who have undergone a hysterectomy, and women who have undergone certain cancer treatments or faced other medical hurdles which doctors declare too great a risk to their own health to carry a baby.

Single men, or those in a same-sex male relationship, also qualify (but not in WA).

McKie says the average surrogacy journey costs about $60,000, although this can vary from $35,000 to $100,000 depending on medical expenses. Many costs associated with surrogacy aren’t covered by Medicare.

McKie, a high school maths teacher, lives in South Australia and has been an egg donor three times and a gestational surrogate for a same-sex couple she met online.

She says surrogates are typically humble about what they do, and are driven to help others.

“Offering to carry a child is the ultimate gift,’’ she says. “We don’t get paid $50,000, our payment in Australia is not a financial one. It’s emotional currency – we’re paid in time and love and friendship.’’

She warns against describing surrogates as “amazing” as they’ll quickly brush it off.

“What Mollie has done and what I’ve done, we really do brush it off,’’ she says. “We just see it as something we wanted to do, and we did it, it was in our capacity, it’s not that amazing.’’

McKie hopes that by sharing their stories, surrogates can help change the world, one conversation at a time.

Raising awareness about surrogacy is something D’Arcy is also passionate about. She charted her surrogacy journey in a private Facebook group for family and friends and is now starting a blog/website to share her story more publicly (thebabybaker.com).

Barnett and Gray-Barnett feel lucky to have found D’Arcy – a once random stranger who is now a dear friend – but D’Arcy insists she is the fortunate one.

“I feel lucky too,’’ she says, adding that she will be forever grateful to her husband for supporting her dream of becoming a surrogate.

“Baby Till’s existence was meticulously planned, yet also an endeavour of chance.

“I’m glad I’ve been able to carry this gift to your door, Dan and Dan. And I’m really enjoying watching you open it.’’•

New series shines light on muttonbirding, wild Bass Strait island

This powerful landmark series, set against the raw beauty of Great Dog Island, is a deeply personal reckoning with heritage, fatherhood and the fragile continuity of an Indigenous tradition

‘Favourite place in the world’: Why actor Pamela Rabe loves Tassie life

She plays commanding, complex and sometimes kooky characters in some of Australia’s best-known films and TV shows. But actor Pamela Rabe also enjoys living a simpler existence in Tasmania