Some of Jeanette James’ earliest childhood memories involve combing remote Tasmanian beaches and collecting tiny iridescent maireener shells with her family. She always enjoyed the process, but it wasn’t until many decades later that she truly realised the importance of those tiny shells and the cultural practice of collecting, cleaning and stringing them into beautiful, handcrafted jewellery, just as many of her Aboriginal ancestors had done.

“My memories are of our family – and that includes extended family, cousins, aunts and grandparents – walking along the beaches of Flinders Island and us children collecting shells,’’ the 70-year-old explains.

“I used to always give my shells to Nanna’’.

At that time, she lived in Tasmania’s North-West and would make the journey to Flinders Island at least once a year to collect shells with her extended family members who lived there.

James even lived on the island for a few years, moving there when she was about eight or nine, until she was 11. She later moved to Tasmania’s East Coast, where she continued collecting various types of shells with her mother for many years, while still returning to Flinders Island each year to collect the sought-after maireener shells.

“I spent many, many years doing the collecting,’’ James, who now lives in Moonah, recalls. “Until about 30 years ago, when my mother said ‘Okay, that’s enough collecting, you now need to learn how to make.’’

James was about 40 at that time, and says it is common for Tasmanian Aboriginal women to spend their younger years collecting shells but not learn the traditional art of stringing necklaces until later in life.

“I think that’s true for many of the shell stringers,’’ she says, of starting the stringing process at 40.

“Because life is busy. You’re raising a family and whilst you can keep up some of your cultural practices, time is in short supply.’’

James says the other benefit of being introduced to stringing later in life was that she had a greater appreciation for the cultural tradition, which she may not have fully understood as a youngster.

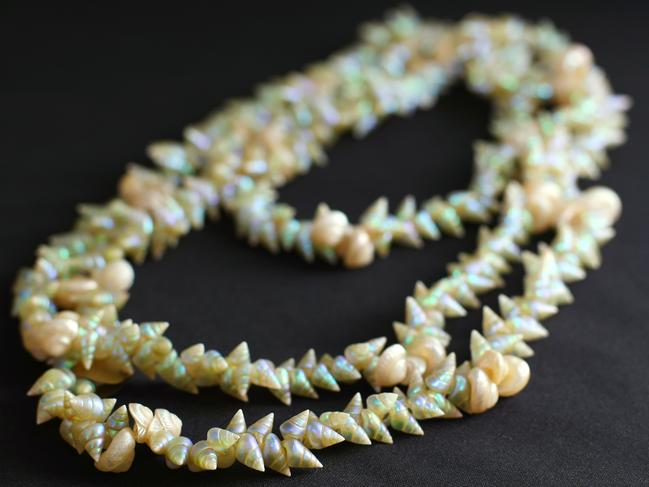

Shell-stringing is the cultural practice of collecting, preparing and stringing shells to make necklaces and bracelets. This knowledge is passed from mothers and grandmothers to their daughters and granddaughters and maintains an important link between traditional and contemporary Aboriginal life.

Pierced shells from Tasmania’s West Coast have dated the tradition back to at least 1800 years ago, and shell-stringing is the Aboriginal community’s longest continued cultural practice.

“I was very hesitant to start with,’’ James says of stringing.

“You’re following a very old tradition; you want to do a good job. But once I started, you don’t look back.’’

She worked closely with her mum, Corrie Fullard, up until six or seven years ago. That’s when her mother, who is now 91, moved into a nursing home.

“I was working with my mother, who was the elder – I felt it was her role to be the stringer and I was learning,’’ James says.

But now she is proudly sharing what she knows with her own children and grandchildren, in the hope of keeping the custom alive for generations to come. And she’s also excited to be showcasing her intricate, handcrafted creations, alongside more than a dozen palawa necklace stringers, in a new exhibition at Bett Gallery that runs until February 4.

kanalaritja tunapri: The New Generation, features work by Auntie Corrie Fullard, Lola Greeno, Charlyse Greeno, Ashlee Murray, Tracey Turnbull, Teresa Green, Zoe Rimmer, Verna Nichols, Emma Robertson, Bec Woolley, Annette Day, Tracy Purdon, Jo Willis, Khristee Willis and, of course, Jeanette James.

James says it’s exciting to share her work with the wider public, but also for her children and grandchildren to see her work on show.

As a caretaker of generations-old knowledge, she is keen to ensure the stringing tradition remains alive.

“I’ve got granddaughters, but they are quite young yet,’’ says James, adding that her eldest granddaughter is 17, while the youngest is only two.

“I’m confident that whilst I can teach them a bit, my sons know enough to encourage them to continue, which is nice.’’

She says it has also been nice to help bring the tradition into the modern era, creating contemporary jewellery using ancient traditions.

When James first began stringing 30 years ago, it was a “labour of love”, with little interest in the handicraft from the wider Tasmanian community.

But as interest in Aboriginal history and culture has surged in recent years, there has been a greater appreciation of stringing skills and a demand for the unique, handcrafted and eye-catching necklaces as wearable art.

“In the early days, it was purely a labour of love, up until the late ’90s and early 2000s when interest (from the wider community) started to pick up,’’ James says.

“For the last 20 years or so, we’ve developed a contemporary line of work and have given the opportunity to interested people to buy pieces of work.

“There’s a huge amount of interest now, which is lovely.’’

Bett Gallery director Emma Bett says visitors literally “gasp with awe” when they see the work by stringers.

The gallery started showing Auntie Corrie Fullard’s necklaces more than 20 years ago and has continued to showcase the work of stringers ever since.

“Auntie Corrie and Carol Bett worked together on educational projects and, through conversations, recognised the lack of awareness of the work of stringers in Tasmania,’’ Bett explains.

“The gallery has had a strong working relationship and friendship ever since, with Auntie Corrie’s daughter, Jeanette James, joining Corrie to hold their first exhibition with Bett Gallery in 2003.

“The necklaces are very popular with art collectors nationally and internationally, and visitors to the gallery literally gasp with awe when we show them the works we have in stock – especially the maireener shells.

“This exhibition is very important as it not only marks 20 years since the first exhibition of necklaces at Bett Gallery, but it is also encouraging newer stringers to become involved at a higher level of making.

“This exhibition sees this important tradition continue to thrive in a contemporary sense, as the art of stringing is passed down from generation to generation – mother teaching daughter, grandmother teaching granddaughter.

“These necklaces are remarkably beautiful, and the women encourage collectors to wear them. This exhibition creates an incredibly important opportunity for collectors to engage in, and support, culture in Tasmania and is a highlight, being the largest necklace exhibition to date.’’

The maireener shell, commonly known as the rainbow kelp shell, was originally the only one used to thread in the necklace-making tradition. There are four different species of maireener shells native to Tasmanian waters, and they come in a range of colours.

James says the blue maireeners – which offer hints of green, blue and purple – are considered the most common, while she also enjoys working with the rarer deep green maireeners which she has carefully collected over many years. Maireener shells can be difficult to find, not only due to their light colour, small size and the limited number of locations in Tasmania, but also because of the state’s ever-changing tides and weather patterns.

There have been times when James has gone searching for shells but has returned home empty-handed. Other times, her collection missions are more fruitful.

“Sometimes you’ll get a handful, if you’re lucky,’’ she explains.

“Or if the wind comes up, you mightn’t find any at all.

“You’ve just got to keep trying, that’s the name of the game.’’

The maireener shells are still considered the most exquisite and prized shells for stringing, but in more recent years, James and other Tasmanian Aboriginal women have incorporated various other shells into their stringing – including black crow, penguin and white button shells – to keep the tradition alive and offer greater variation in their artistic creations.

And James says this adds a new level of excitement to the traditional craft, as more Tasmanians are able to engage in the practice and share it with new generations.

“To continue on, you have to diversify, you have to find other collecting areas,’’ she says.

“Tradition is not a static thing. You need to make your own traditions. That’s what’s so exciting about having so many women in this exhibition. They are our knowledge holders – our future knowledge holders.’’

Among those future knowledge holders are sisters Emma Robertson and Bec Woolley, who are relatively new to stringing and are both showcasing work in the exhibition.

Robertson began stringing several years ago and it’s a skill she has taught her sister in more recent times.

Both live in Hobart’s northern suburbs and work for Karadi Aboriginal Corporation, an organisation that is run by Aboriginal Tasmanians to support other members of the wider Indigenous community and foster strong cultural identity.

Stringing courses have been run at Karadi in the past by elders to teach the tradition to younger members of the Aboriginal community, which is how Robertson came to be involved in stringing. And it was a skill she was keen to share with her sister

“It’s just something I shared with Bec that we now do together,’’ Robertson explains.

“We’d shelled a lot but we hadn’t been stringing necklaces together.’’

Robertson says there’s something very special about collecting and stringing shells that makes her feel connected to the land and her forebears.

“I love being on Country,’’ she explains. “It gives me a close connection to our ancestors.’’

And the 43-year-old says the older she gets, the more she appreciates the knowledge that has been handed down from her elders.

“I’ve got young daughters,’’ says Robertson, who is a mum to Hollie, 23, Pyper, 13 and Lainee, 11.

“My kids all come out on Country with me and are learning from a young age. It has come full circle – something that was almost lost is now being learnt by children again.

“The tradition is pretty much unchanged since old people used to do it. I do a lot of contemporary (jewellery-making) but the process of going out and collecting shells remains unchanged.’’

The sisters travel the state collecting shells, fitting in trips around their busy work schedules.

“We both work full time and have families … it (life) gets in the way of me wanting to practice my culture. I have so many ideas but I don’t have enough hours in the day.’’

Robertson says collecting shells isn’t a quick process.

“We can be looking for hours, sometimes days,’’ she explains.

“Some shells that Bec and I collected took us four days.

“You’re working within the tides – you might only have two to three hours out in water that you can collect shells. It takes a lot of working out. We’ve got the tides mapped out for next few months.”

Some shells are found in the water, while others can be found washed up in the shallows, on the shore or clinging to rocks along the coast.

Robertson says the act of collecting shells takes on an almost meditative quality and is a great bonding exercise.

“It’s something that Bec and I get to share together,’’ she says.

“We could be out in the water for hours and not say a word to each other. We’re both present in the moment.

“Other times, we’ll talk about our deepest and darkest problems and leave it all out there in the water. That’s the mental health aspect of it.’’

Even once the shells have been collected, a lot of work goes into cleaning and carefully punching holes in them so they are ready for stringing.

“Collecting and cleaning – it can take a lot of time,’’ Robertson explains. “And putting the holes in the shells … after all the time it takes to collect the shells, you don’t want to ruin them when you’re putting the holes in.

“Then there’s sizing them and stringing them, making patterns and thinking of your shapes. It’s a massive process and I think people appreciate that.

“It’s not something that is made in 30 minutes and is mass-produced. It’s wearable art and culture and the tradition of thousands of women before us.’’

The sisters are descendants of well-known Tasmanian Aboriginal woman Fanny Cochrane Smith, an influential matriarch who was born in 1834, had 11 children and passed on a rich treasury of cultural knowledge, including fishing and hunting skills, bush tucker and bush medicines, basket-making and necklace-stringing.

Cochrane Smith also established a name for herself as a Hobart celebrity until her death in 1905 at the age of 70, performing at Hobart’s Theatre Royal.

Her songs are among the earliest musical recordings ever created and the most treasured recordings of early Tasmanian Aboriginal song and speech.

Historical images of Cochrane Smith show her proudly wearing a statement necklace, handcrafted from shells, and Robertson and Woolley have set themselves a goal – to replicate this necklace to keep as their own.

Woolley is relatively new to stringing – she has collected shells for many years but only started stringing about a year ago, learning the art from her sister.

She says one of the highlights was seeing one of her necklaces gifted to federal Minister for Indigenous Affairs Linda Burney – a proud member of the Wiradjuri nation – in Hobart late last year.

Woolley says it’s hard to put into words what a special experience stringing is.

“I go off into my own world when I’m stringing,’’ the 39-year-old says.

“When you finish a necklace, you just get such a special feeling. It’s my happy place.

“Also, to learn from the elders who are sharing knowledge with me that I don’t have, that is pretty key to it as well.

“The elders won’t tell you exactly where to go (to find shells). You might go out shelling and not get any shells.

“Emma and I have driven the state and stopped at just about any beach or waterway where you might find shells. It’s all part of the learning.’’

Woolley says it’s nice to know she and her sister are playing a small part in helping to keep the cultural knowledge of their ancestors alive. And it was encouraging that the wider community was becoming fascinated by the process of stringing, too, while acknowledging the time, effort and skills involved in crafting each individual shell necklace.

“Stringing is becoming more celebrated, definitely,’’ Woolley says.

“People are appreciating the hard work and dedication that goes into it.’’

James agrees.

She says there is a desire to honour the elder stringers and uphold a high quality of work, while also celebrating Aboriginal culture and protecting the art of stringing for future generations.

“There is an expectation for us, as a group of Aboriginal women responsible for maintaining such an important part of our culture for future generations, to follow cultural protocol: look after Country, understand the environment and how to sustainably collect the shells and protect the seaweed beds,’’ she says.

“It’s a special tradition to be a part of.’’•

See the work of Jeanette James, Emma Robertson, Bec Woolley and other palawa necklace stringers in kanalaritja tunapri: The New Generation at Hobart’s Bett Gallery until February 4.

Ultimate guide to what’s on in Tassie this summer

Summer is coming! Make the most of the warmer weather with our go-to summer events guide – it’s packed with must-do Tassie activities to enliven your social calendar and kickstart 2026 in style

Gus Leighton – on sax – brings Tassie party vibes to the max

Whether he’s firing up a dancefloor, improvising in a jazz quartet or swinging kettlebells like a pro, Tasmanian saxophonist and gym-enthusiast Gus Leighton loves being the life of the party.