Talking Point: Don’t develop Lake Malbena — keep Reg Hall’s vision alive

Bushwalker and lawyer Reg Hall had a simple vision — Tasmania’s pristine wilderness should be preserved. He would not have wanted the Lake Malbena development, says John Hall.

Opinion

Don't miss out on the headlines from Opinion. Followed categories will be added to My News.

I WRITE in sadness about the planned destruction of the vision of my late father Reg Hall, who helped nurture the wilderness of Tasmania.

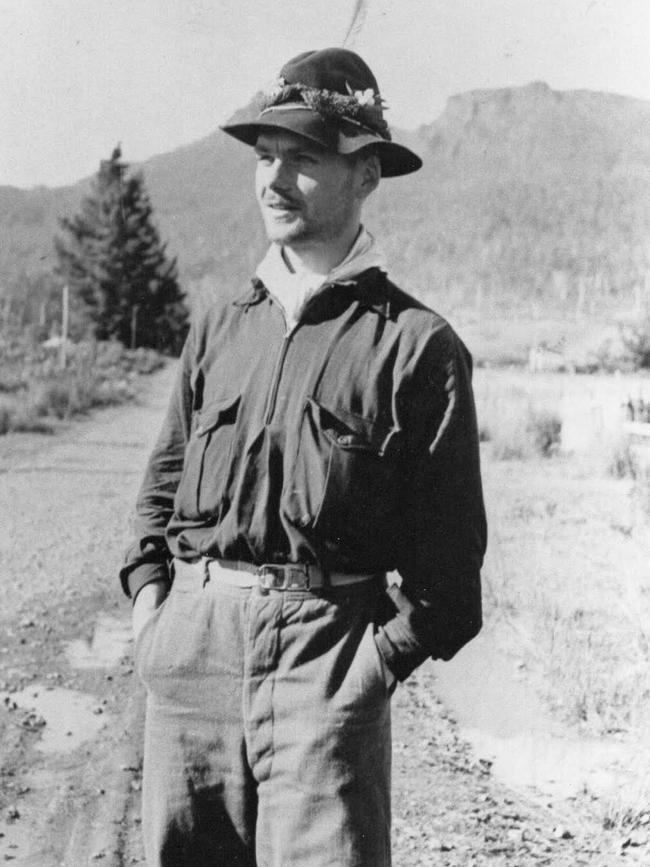

Reg was a Launceston lawyer and an ardent bushwalker. He had a simple, perhaps primeval, vision: Tasmania’s pristine wilderness was unique on our planet and should forever be preserved.

Reg was president of the former Northern Scenery Board (with a focus on Ben Lomond, where he was a keen skier). He was also on the inaugural board of the Cradle Mountain-Lake St Clair Scenic Preservation Board.

From the late 1920s and after World War II, Reg spent weeks each summer away from his desk in Launceston — and from his family — to explore the Tasmanian bush — the peaks and lakes, the stands of ancient trees, the fauna.

He stepped carefully, avoiding sphagnum moss and cushion grass, nurtured by nature over the centuries, now partly protected by boardwalks in Tasmania’s national park, but increasingly vulnerable to the ravages of fire.

In the 1930s Reg’s exploring eyes turned east from Cradle Mountain, towards the neighbouring peaks of the Tasmanian wilderness — what is now known as the Walls of Jerusalem National Park.

My father gave biblical names to 20 of the main features of the exquisite amphitheatre of the Walls — among them Damascus Gate, the Wailing Wall, the Pool of Siloam and Herod’s Gate. Reg was not a churchgoer; his place of worship was Tasmania’s wilderness.

In the early 1950s he was issued a permit by the State Lands Department to lease a small island on Lake Malbena.

On this little island — now identified as Hall’s Island — Reg built his rustic hut out of local rocks and timber, and sheets of iron and timber flooring dropped from a Cessna. On our living room floor in Launceston he spent hours assembling a collapsible canoe that would carry him from the shore of Lake Malbena to his island.

My father used his island “home’’ as a base to explore beyond the Walls, which he now knew so well. He carried his canoe on his shoulders across the high country to numerous lakes and tarns dotted between the Walls and the Du Cane Range to the west. Reg called it “the land of 1000 lakes”.

My father produced the first map of the Walls of Jerusalem.

He also informed the walking clubs of Launceston and Hobart that his island hut could be used as a refuge for their bushwalking members, and provisions were always left for them in an emergency. Those who needed to know could find a small marine-ply dinghy hidden on the shoreline and, in later years, an inflatable dinghy to carry them to the island.

I hope the hut will remain a refuge in the Tasmanian wilderness for genuine bushwalkers.

But unless there is government intervention it will become an inappropriate commercial venture, with helicopters flying regularly over part of the Walls of Jerusalem National Park to land a privileged few.

One topographical feature in the Walls of Jerusalem Reg did not name was later known as Hall’s Buttress, which I ascended in 1960, in part as recognition to the vision of my father, who would have climbed the peak more than 30 years earlier.

My father died in 1981. As his only son, I know that if he were alive today he would be appalled by the plans to expropriate Hall’s Island — the island “home’’ used by fellow bushwalkers — for an eco-tourism venture that includes 240 helicopter flights a year over the Tasmanian wilderness.

I ask both the federal and Tasmanian governments: take into account the vision of Reg Hall for this pristine speck on the world map, and refuse permission for the proposal that’s currently before you.

John Hall grew up in Launceston. Now retired, he was a journalist on major publications in Australia, Canada and Britain. In the late 1990s John and his wife Suzanne restored the historic mill on Richmond Bridge and received a national award from the Master Builders Association. They now live in Melbourne, to be close to their two children and three granddaughters.