Charles Wooley: Veterans remind us not to take peace for granted

As a young reporter I interviewed a lot of veterans of both wars. I don’t remember any of them who recommended the practice, writes Charles Wooley

Opinion

Don't miss out on the headlines from Opinion. Followed categories will be added to My News.

“Taking the biscuit” was an old expression you don’t much hear now. It usually meant the end was nigh. It related to the Roman Catholic sacrament of last rites and “the biscuit” referred to the wafer taken as death nears.

In the late 1980s I remember hearing such droll euphemisms in northern Thailand from some old diggers, ex POWs who were returning to the infamous Burma Railway.

“Mate there’s not many of us left now,” one old digger called Snow Pete told me. “The rest are pushing up daisies. They have hopped off the twig.”

“Yeah, we’re the last of the Burma Railway mob,” Snow’s best mate Dutchy Holland agreed. “A lot of them have had the biscuit.”

Around this time of year having the biscuit was something my primary school mates and I looked forward to.

Anzac biscuits.

We loved them sweet and chewy in the middle and deliciously caramelised. And at the edges we preferred them crunchy and just short of being burnt.

I remember my mum Ella, knocking them up in just one large green bowl. Rolled oats, butter, flour, brown sugar and golden syrup whipped up with a wooden spoon into a thick sticky mixture.

Then, spooned out and pressed onto a tray lined with baking paper and into the oven for just enough time to become golden brown in the middle and of course darker at the edges.

I can actually smell them as I write.

Some mothers added coconut. That was good too.

A few days later, if there were enough of them to last, the Anzacs would harden to become “dunking biscuits”.

Then they were softened by being dipped in a cup of tea and sucked rather than chewed.

That was the good part of Anzac Day.

The rest was a bit of a horror show.

At Mayfield Primary School (aka the North Launceston Juvenile Correction Facility) we were lined up on the quadrangle under a blazing sun, like so many tiny POWs, and lectured on the horrors of war.

Old diggers, many in their army uniforms, would relate tales of the appalling tortures they received at the hands of their Japanese captors.

I won’t spoil your Saturday breakfast, but it gave us nightmares and was almost enough to put us off our Anzac biscuits.

Almost.

And there were even older blokes from World War I, the original Anzacs. The stories they told were of the horrors not of captivity but of the battlefield.

Of death and worse, of terrible wounds received in taking some hill that didn’t matter. Of the apparent meaningless sacrifice of men ordered into a hail of bullets and the incompetence of the generals who issued those orders from safety, way back behind the lines.

In retrospect it was unsurprising that when our time came, so many of my generation where unenthusiastic about going to Vietnam.

As a young reporter I interviewed a lot of veterans of both wars. I don’t remember any of them who recommended the practice.

By the 1980s the type of blokes who had come to my primary school were a vanishing tribe.

They were the same decent, unassuming men and many of them still seemed strangely haunted.

My schoolboy memory was that they were skinny and their old army clothes hung so loosely on them. Years later they hadn’t much changed and reminded me of the salutary description from the poet Yeats:

An aged man is but a paltry thing,

A tattered rag upon a stick.

One of my old diggers even made a dark joke about being a member of the “Changi Weight Watchers”.

Snow Pete whom I interviewed on the Burma Railway, the so-called Death Railway, was one who survived to make it back to the infamous Changi POW camp in Singapore.

“After where I’d been, Changi really wasn’t that bad,” he said. “I kissed the ground when I got to Changi. It was paradise. They had a tap at Changi.”

How, I wondered, did some men survive privation while so many died?

Snow told me how. “I remember the Japs gave us a stew to eat and a big bloke beside me said, “Strewth I can’t eat this s***. It’s got maggots in it.”

“I said, ‘Mate give it to me. I’ll eat it’.

“And I said to myself, ‘beauty, this is my ticket out of here’.

“The big bloke never made it home.”

Over years of reporting on Anzac Day stories from the Somme to Sandakan it became increasingly obvious that many of our returned men had difficulty coming to terms with the new world to which they returned. Enemies had become friends and old allies had become enemies.

I can remember ageing returned warriors in a Queensland RSL club raging on camera about how the Japanese were, “Invading and buying up the Gold Coast”.

While outside, the car park was packed with Toyotas.

I’ve been to a few wars, not as an intrepid reporter but as a sensibly cautious one.

I have never felt that my mob, the Wooleys, were particularly warlike although we have been in a few stoushes.

The first Wooley I know about was Abraham, an officer from Sheffield in England who served under the Duke of Wellington, at Waterloo, which as the duke conceded, “was a close-run thing.”

I know nothing but somehow doubt my ancestor made much difference.

Another Wooley fought in the Māori Wars and in Africa against the Zulu. Not such good causes, so I move on to my seafaring great grandfather Captain Charles Wooley.

In Fiji he accepted the surrender of the famous World War 1 German raider Felix Graf von Luckner who was credited with sinking 14 Allied ships.

Captain Wooley was so nice to his famous guest that Count Luckner presented his fine German binoculars inscribed as a gift to a friend.

My grandfather, another Charles, was at Anzac Cove, fortunately as a sailor with the Kiwi navy. He told of putting men into wooden boats and seeing them off into a storm of bullets and being, “Very happy I was a sailor and not a soldier.”

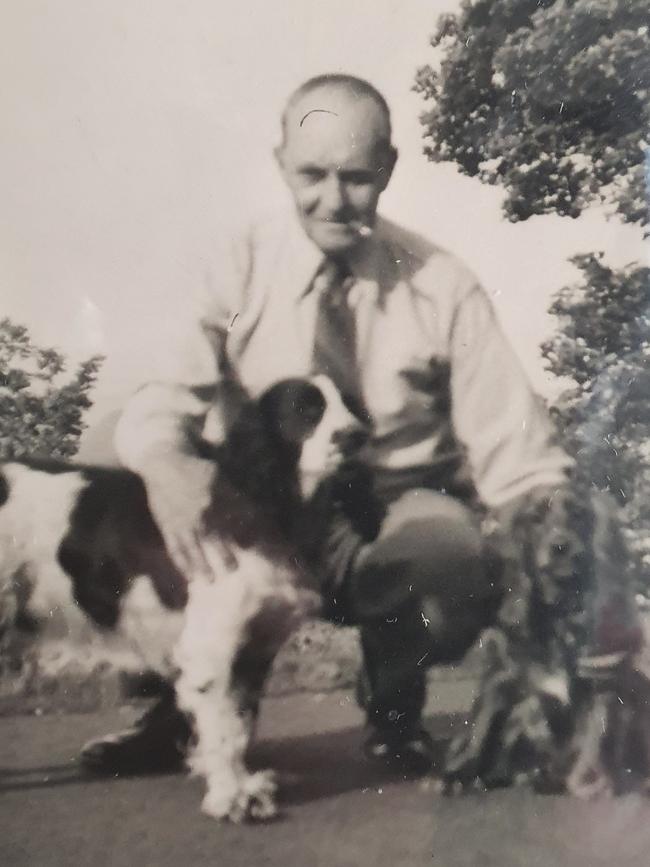

And finally, Charlie, my dad who spent “the last great unpleasantness” as he called it in the Fiji Defence Force.

The Japanese never got to Fiji but that didn’t stop him firing a shot in anger.

One night, the two Fijian battalions each thought the other was the enemy. “We blazed away all night and felt very silly in the morning,” he told me.

“We couldn’t have been very good shots. No one was hurt.”

Since then, none of my mob has ever joined up.

My own enthusiasm for armed combat still remains limited to the consumption of Anzac biscuits. Sadly, they were unavailable at the service I attended this week.

But should Australia ever call upon me, know that do I stand ready to serve my country.

I still have mum’s recipe and the wooden spoon.

Charles Wooley is a Tasmanian journalist and deputy mayor of Sorell.