‘Not that simple’: What’s really causing Australia’s housing and rental crisis

Aussies have been hit hard by the Reserve Bank’s brutal interest rate hikes – and now, a very weird pattern has started to emerge.

National

Don't miss out on the headlines from National. Followed categories will be added to My News.

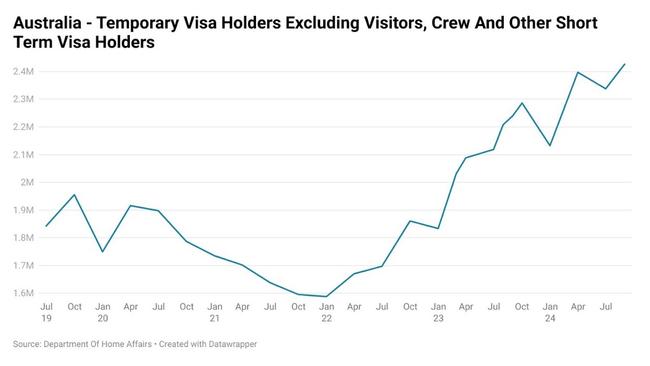

For much of the little over two and a half years since Australia reopened its international borders in early 2022, the issue of the impact of migration on housing has been a hotly debated issue.

Arguably, part of the issue with the debate is how broadly it is approached.

While it can be debated that it’s a matter of perspective, it is effectively two at times separate issues: the housing market as measured by housing prices, and the rental market as measured by rents and vacancy rates.

It could be easy for a casual observer to conclude that migration has no impact on housing. During the pandemic, net migration was in reverse a sizeable proportion of time, and despite hundreds of thousands fewer people in the country, housing prices rose extremely strongly.

But as one might expect, it’s not that simple.

The pandemic and the rental market

In reality, the reversal of net migration and the pandemic had an almost immediate effect on rental markets throughout the nation, but in very different ways.

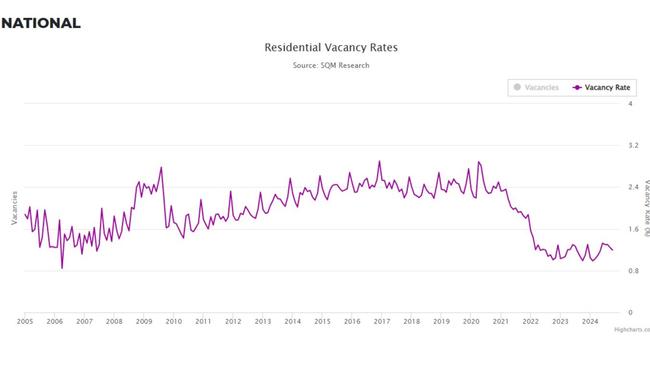

In Sydney and Melbourne, rental vacancy rates surged to the highest level in at least 15 years amid an exodus of temporary visa holders and renters returning home to weather the pandemic with family.

The epicentre of the rise in vacancy rates was in locales with high numbers of temporary visa holders, such as the nation’s CBDs.

If we use the last non-lockdown impacted month, February 2020, as our benchmark, asking rents in Sydney in aggregate fell by 12.1 per cent, bottoming out in October that year. In Melbourne, rents also fell by 12.1 per cent, but didn’t bottom out until May 2021.

But at a national level, there was no such fall – quite the opposite. By the middle of 2020, the impact of people moving out of the nation’s cities and into the regions had already seen the national average asking rent begin to take off.

As 2021 dawned, Australia’s rental market was primed for a collapse in vacancy rates that would ultimately result in the current rental crisis across much of the nation.

Housing market

While there will always be a proportion of migrants who have the means to buy a home shortly after arriving in Australia, they are a relatively slim minority. The overwhelming majority of the impact on the housing market from migrants occurs over time.

According to figures from the Australian Bureau of Statistics, for migrants who have been in Australia for up to five years as of the latest census, 27.9 per cent own their own home either outright or with a mortgage.

For migrants who have been in Australia for five to 10 years, 55.6 per cent own a home outright or with a mortgage.

If we assume permanent migrants have roughly an average household size, those who arrived in the last 10 years as of the last census owned a total of 307,600 homes. To put this into perspective, this is roughly 30 per cent of all first homebuyer finance commitments that occurred during the decade covered by the data.

Migration after the pandemic

When the nation reopened its international borders in February 2022, an acute shortage of rental accommodation was already in full swing. Despite the exodus of hundreds of thousands of temporary visa holders during the pandemic, the changing way Australians lived demanded more and more homes in places where there simply wasn’t enough.

The surge in migration that followed did not create the rental crisis, but it has played a major role in it becoming entrenched and remaining acute.

According to figures from property data firm SQM Research, the national rental vacancy rate remains at a level unseen at this time of year, in the almost 20 years of data SQM has collected.

To put the current state of rental vacancy rates in perspective, in October 2019, 2.3 per cent of rental properties were vacant. Today, the figure is 1.2 per cent.

The rental crisis broke the housing market

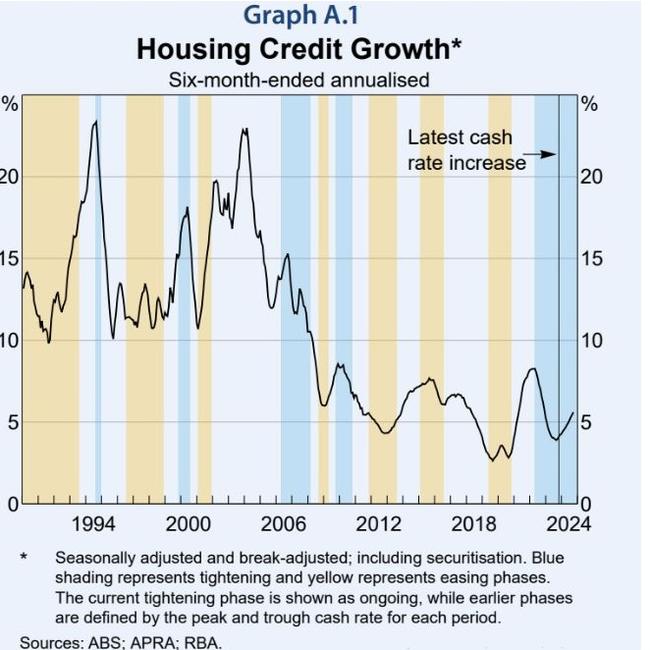

Historically, housing credit growth has generally slowed significantly following Reserve Bank of Australia rate rise cycles, as illustrated by this chart from the RBA’s recent Statement on Monetary Policy.

Yet in the current rate rise cycle, an abnormal trend has emerged – housing credit growth has re-accelerated, without being provided with the traditional catalyst of lower interest rates.

One would think at first glance that one of the hardest-hit cohorts by the record high rise in relative mortgage rates would be first home buyers. This was the case following the 1994 and 2009 rate rise cycles, with the rolling annual number of first homebuyer finance commitments falling by 22.5 per cent and 51.5 per cent respectively over the following 18 months.

Unlike previous cycles, which saw the number of new mortgages flowing to first home buyers continue to dwindle over time as higher rates continued to bite, the current cycle saw the number of new loans bottom out in just 10 months, and then begin to grow again.

Amid the extremely challenging environment of the rental crisis, many recent first home buyers did everything they could to escape those conditions and get into their own home.

According to figures from investment and advisory group Jarden, up to 75 per cent received family assistance to purchase and roughly a third used various federal government support programs such as the First Home Guarantee to get into the housing market.

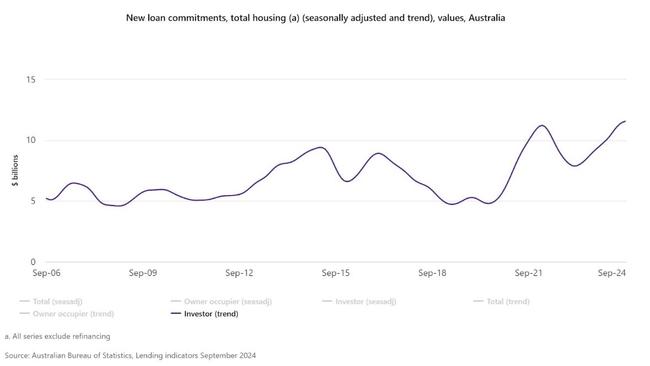

The rental crisis also supported the housing market through another mechanism – property investors.

Rather than investors being forced to come to terms with a sizeable rate rise cycle in an environment of average rental price growth, the expansion of demand for rental accommodation driven by migration at a time when the rental crisis was already underway drove rental price growth even higher.

In time, the surge in rental returns and the resumption of price growth incentivised more property investors into the market, supporting housing prices. According to the latest figures from the ABS, the amount of housing credit flowing to property investors is at an all-time record high in trend terms.

The balance

When it comes to the rental market, migration levels are generally the most influential demand side factor. With the exception of the closed border era of the pandemic, net migration has been the largest driver of population growth for the rest of the last 19 years.

But the market to purchase homes is another matter.

While migrants are a significant factor in overall demand, the number of homes purchased by migrant first home buyers each year is less than a quarter of those purchased by property investors, as of the latest figures.

However, in the current economic cycle the rental crisis, which has been exacerbated and prolonged by the record high level of migration, has played a significant role in supporting housing prices.

Ultimately, the interaction between migration and the rental and home purchase markets is a complex and nuanced one. Its impact can vary in the two respective markets depending on the circumstances, but it nonetheless remains a key consideration in determining the balance of supply and demand.

Tarric Brooker is a freelance journalist and social commentator | @AvidCommentator

Originally published as ‘Not that simple’: What’s really causing Australia’s housing and rental crisis