Wife tells of how botched cancer surgery turned her husband into a complete stranger

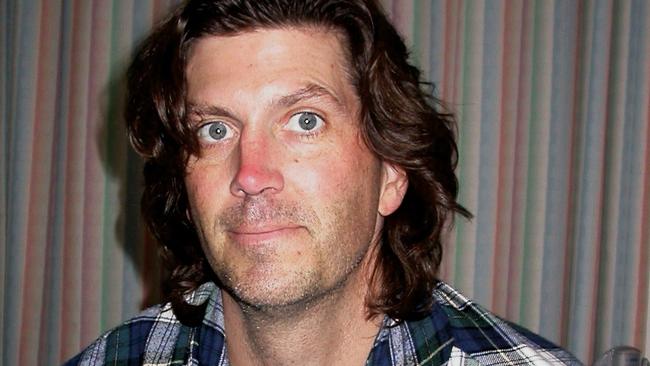

THE 10-hour operation is called ‘the mother of all surgeries’. It saved Richard Bandy’s body, but he woke up a completely different person.

Lifestyle

Don't miss out on the headlines from Lifestyle. Followed categories will be added to My News.

SONYA Lea, just shy of 17, spotted a bear of a young man across the floor at her high-school dance in Ontario, Canada. He was tall, beautiful, verbose and entirely at ease.

Richard Bandy introduced himself, and before she knew it, they were dancing, bodies swaying to the Beatles’ Penny Lane. He impressed her with news that he had won a debate contest that earned him a trip to the United Nations.

“I was drawn to him instantly. We bonded over a shared love of language,” Sonya says, her voice softening as she conjures up the meeting. “He was a force to be reckoned with.”

When he asked for her number, she didn’t hesitate. He called the next day, and they have been together ever since, celebrating their 32nd anniversary this summer.

They faced struggles. Two children and a move to Seattle took their toll. He worked too hard, running 21 physical-therapy clinics while seeing patients, and struggled with anger issues; she wrestled with alcoholism. But they loved each other and love conquered all, they thought.

In 2000, Richard, 42, was diagnosed with a rare form of cancer called pseudomyxoma peritonei, which occurs when cancer cells invade the mucus surrounding the body’s internal organs. The couple attacked this scare like any other: He went into surgery, underwent treatment, and they went back to their lives.

Three years later, it came back. This time, a more dangerous experimental surgery, colloquially called “the mother of all surgeries,” was required.

It saved his body. He lost his life.

A CHANGED MAN

Sonya Lea’s new memoir, Wondering Who You Are, describes the remaking of a marriage after the man she fell in love with became a stranger. A mistake during the cancer surgery robbed him of his personality and many of his memories.

“I had to say goodbye to the former man,” Sonya says. “I had to come to terms with the reality that the old man cannot be rebuilt.”

In the 10-hour surgery, called cytoreduction hyperthermia intraperitoneal chemotherapy, doctors cut Richard from pelvis to sternum to access his organs, removed his organs and scraped them clean of any cancer-containing mucus. Then a chemotherapy solution heated to 107 degrees was poured into his abdomen to kill any remaining cancer cells.

The surgery went as planned — with one complication. The surgeon nicked one of Richard’s organs, causing him to bleed internally.

The clock ticked in the ICU as Richard’s blood pressure dropped and three pitchers of blood pooled in his abdomen. Because of a false normal test after the surgery, the hospital waited precious moments before ordering blood and calling in the surgeon. Without proper oxygenation, it takes four minutes for brain-cell death to occur. Richard went without for at least 10 minutes.

When he awoke the next day after the second surgery, Sonya immediately knew something was amiss. Even though he was still intubated and could communicate only through writing, she noticed he was flat and detached, and she didn’t recognise his slanted, messy handwriting.

The doctors attributed his altered behaviour to the surgeries and the drugs. But days later, as the morphine tapered off, he remained changed.

He could recall basic facts — his name, his wife’s name, the president’s name, semantic memories — but memories involving more complex and deeper emotional resonance, called episodic memories, were blank.

His demeanour, once commanding, was now apathetic and submissive. When she instinctively handed him a list of questions for the doctors, “which was something he would normally do — he was the kind of guy who liked to direct traffic,” he stared at her blankly.

“That’s when I started to realise something was fundamentally different about this man,” she says.

The doctors noted it, too, and during one interaction with the surgeon, he the surgeon suggested Richard suffered from a “hypoxia anoxic insult,” or a brain injury caused by loss of oxygen.

Richard’s behaviours were typical following a loss of oxygen, explains Dr. Barry Gordon, a Johns Hopkins behavioural neurologist and cognitive neuroscientist.

“The areas of the brain that require lots of oxygen and blood get damaged more than others,” he says. “The hippocampus is one of these areas … and the other area that often gets damaged is often the cortex of the frontal lobes.”

Gordon speculates that the damage to Richard’s brain may have altered or destroyed the circuits involved in storing memories, not only those involved in organising and retrieving them.

“In his case, I suspect that his personality was truly changed,” he says. “Your personality is largely made up of your memories.”

A 42-YEAR-OLD ‘VIRGIN’

A month later, Richard was released from the hospital. Cognitive tests showed he was disabled. Short- and long-term memory, as well as global cognition, were severely impaired. Asked to name animals that start with a “C,” he could not conjure up a single example.

Once a loquacious social butterfly, he emerged a quiet, unobtrusive and passive man, who went for hours, if not days, without saying a word. Inhibition replaced self-consciousness. He had to be reminded not to belch in public, to cover himself in front of his daughter, to soften his fixed gaze (common among those with brain injuries) when he was in public. He cried almost every day.

Other personality quirks came later. He started called Sonya “sweetness,” a pet name he never used before. He slept on his side in a foetal position instead of on his back and developed a taste for food he once hated, like brussels sprouts.

Days revolved around eating, sleeping and attending speech and cognitive therapy.

Six weeks after surgery, Richard reached for his wife in the middle of the night, the first time he had expressed desire.

Lea climbed on top of her husband and watched his face as it became “clear to me that he was having a completely fresh experience … Across his face, none of his former gestures. He hadn’t known what you were going to do, what your touch was going to be like,” she writes.

“Honey,” she recalls saying, “I have to ask you. Whatever your answer is, it’s OK.”

He nods.

“Do you remember sex?” she asks.

“I don’t think so,” he says.

It was a soul-crushing moment. Until then, she had secretly harboured the belief that an intimate act like this would bring him back to her in full. Now it was clear: The man who had taught her about sex had become a virgin. Her husband was no longer her husband.

MOURNING A MARRAIGE

Sonya spiralled into a deep depression after this encounter, finding herself crying for weeks on end. She contemplated leaving him and told him she was unsure if she could function as his wife and his caregiver.

“I was grieving not just for him but grief for the former marriage,” she says. “All of those ways that we built our lives with each other, the nuances and flirtations, the shared history. And the sexual experience, because that was important to us, and that was lost.”

Forgotten, yes, but perhaps not lost.

Richard was tenacious in his approach to recovery — his goal was to return to work as a physical therapist — and Sonya was steadfast in her support.

They set up an hour-by-hour calendar for him and set alarms to remind him to take his vitamins or put clothes in the dryer. Sonya placed a list of questions by the phone so when relatives called, he would know what to ask.

He spent hours studying anatomy and physiology textbooks and eventually retained enough information to return to work as a therapist part time.

After their daughter graduated from high school, a year after the surgery, they decided to take an extended trip to France. There, Sonya says, the rekindling began, and it continued after they returned to the States.

“I show him simple things — kissing, touching, the mechanics of moving the body,” she writes. “I demonstrate affection: compliments, rapport, embraces, caresses, calls, catcalls, the French kiss. Every suggestion, forgotten. Every action, forgotten. In order to adopt the behaviour, he needs to be reminded. Not dozens of times. Thousands of times.”

But their sex life remained an unresolved, thorny issue. Sex with Richard, Sonya writes, was like making love to a randy teenager — no finesse, seduction or nuance, and he couldn’t seem to learn how to evolve.

She suggested taking on a lover, and over many conversations, he eventually agreed. She answered personal ads and even developed a relationship with a writer. She did not tell this man she wanted him to teach her husband how to make love to her — but that was the intention.

“I fall in love with all of us, with the sexy soirees, with the effortless communication, with the three of us walking together under streetlights laughing about our unusual alliance,” Sonya writes. “I’m living a Tantric party, an unabashed adventure, a dream … We fall asleep talking, and wake up holding each other.”

A NEW LOVE

It was not to last. Her husband told her he didn’t want her to hang out with the writer alone, but she did anyway.

She discussed going on a beach vacation alone with the writer, and even departed for the trip, only to turn around after the writer told her Richard had been crying on the car ride to the airport. After this, she decided to rededicate herself to the marriage.

It took nearly a decade to get to where they are now, but they have finally found a place of “great sexual maturity.”

She accepts that he will never be the man he was before and that even with all the coaching in the world, most of those memories will never be unlocked, because they might no longer exist.

Richard himself admits that there are still wide swathes of his life that he can’t remember — and that this likely will not change.

But in understanding Richard, Sonya has found a lot to love: a generous, sensitive man, very affectionate, who adores his wife.

Richard has returned to work full time as a physical therapist and runs a clinic. They settled a malpractice suit against the hospital.

Their love now goes beyond “personality and identity,” Sonya says, “his unconditional love and acceptance has taught me how to do that in a way I might never have known if this didn’t happen.”

But would that 16-year-old girl at the high-school dance be attracted to this new, quiet version of Richard?

Lea pauses before answering.

“No, I don’t think so,” she says. “Not as the woman I was before. But I have also changed, and I’m very drawn to this man as the woman I am now.”

Originally published as Wife tells of how botched cancer surgery turned her husband into a complete stranger