There’s something about Port Davey in Tasmania’s deep south that keeps drawing you back. Just ask Peter Marmion who arrived at Melaleuca as a 16-year-old back in the early ’70s and came across a stooped old man carrying a load along a track near the airstrip. “We stopped and started to chat. He could see it was going to take a little while so he put down his load — which consisted of two sacks. After a while he invited us in for a cup of tea and my mate and I offered to carry his bags.

“There was flicker of a smile and he slowly said: ‘Yeah, that’d be nice’. Well, we reached down to lift the bags and it was as if they were bolted to the ground … we couldn’t budge them an inch.”

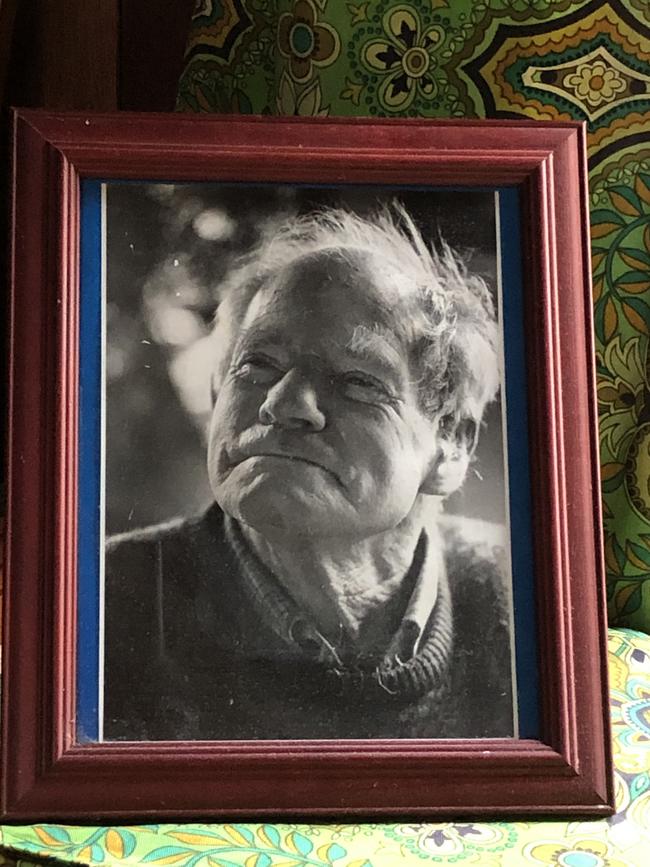

The bags were filled with tin ore and weighed about 50kg each, and this was Peter’s first encounter with the legendary wilderness naturalist and tin miner Deny King.

It was a memorable introduction. Like those bags of tin, there’s an immovable force about this ancient part of Tassie which weighs on your mind long after you’ve left.

Peter has been returning to Melaleuca — the landing base to explore Bathurst Harbour and Port Davey in Tasmania’s remote South West National Park — for 50 years, and his vast knowledge of the area is a key part of a two-night, three-day wilderness experience run by Tasmanian company Par Avion.

Peter is joined by fellow guide Greg Wells, another veteran of tourism in the region, who has been taking groups into the ancient wilderness for more than 25 years. Our trip has been delayed by the tail end of a south-westerly storm, which are pretty common along a coastline which cops the worst of the Roaring Forties.

“It’s kind of appropriate that Mother Nature decides when you can come and go,” Greg says. His comment highlights a respect for the elements which have shaped the landscape for thousands of years. It’s a privilege to be there. It’s not to be taken for granted.

What Greg and Peter don’t know about Port Davey isn’t worth knowing. And what a pair of great storytellers — their admiration and passion for the World Heritage area is clear from the yarns they weave filled with warmth, humour and an encyclopaedic knowledge of the flora and fauna.

From the moment we touch down on the 450m quartzite airstrip Deny built at Melaleuca in 1957, the rich oral history lesson begins. It seems every landmark carries a tale — often involving hardship, tragedy or acts of endurance. Over the next three days they lead an exploration of the coves and landmarks within Bathurst Harbour, Port Davey and Melaleuca.

We visit TV Hill and, of course, there’s a yarn attached. The hill is a short climb up from the former home of Clyde and Win Clayton, tucked inside the entrance to Bathurst Harbour. The story goes that Clyde was putting up a TV antenna on the hill to catch the faint ABC TV signal and kept calling down to Win in the house below.

“Is this it?” he called. “No nothing there, try somewhere else,” came the reply. “What about here?” No, still no good.” An increasingly frustrated Clyde tried repositioning the wire for a good hour until he threw down the antenna in disgust and announced he was coming down for a cup of tea. “That’s it … you’ve got it!” an excited Win yelled back.

No aerial remains on the hill but it offers our first vista of Bathurst Harbour — a huge expanse of water which, combined with Port Davey, is three times the size of Sydney Harbour.

It becomes clear that this magical place is dominated by mountains and water and to make the most of a trip here a boat is a must.

Fortunately Greg is an excellent skipper and he manoeuvres the flat-bottomed Wilderness Explorer I expertly over the coming days. He’s ably assisted by Peter, a veteran of Sydney-Hobart yacht races, whose seafaring skills are demonstrated in the way he effortlessly knots a bowline without thinking.

Bathurst Harbour forms part of the Port Davey Marine Reserve, which contains a rare collection of plants and animals. The tannin-stained freshwater leached through the peaty soils of the surrounding land overlays salt water carried in from the Southern Ocean, creating an extremely dark environment. This allows for a colourful variety of plants and animals, normally found in the deepest and darkest parts of the ocean, to thrive.

Delicate invertebrates, including sea fans, sea pens and sea whips, live alongside soft corals.

We settle in at Par Avion’s standing camp which provides plush low-impact accommodation in the wilderness. The brochures describe it as a luxury camp, which may be overstating it a little, but the hexagonal canvas yurts are clean with wooden floors and warm, comfortable doona-covered beds and a hot-water bottle available at bedtime. Hot showers in a shared toilet block means this is a far cry from serious camping. All the meals are cooked for you with delicious Tasmanian produce and wines. Pre-dinner drinks with cheese platter and nibbles all combine to make it a memorable part of the trip. The itinerary is dictated by the weather and there is ample opportunity to capture the history and highlights of the pristine and ancient environment.

On the second day we set out beneath overcast, showery skies and shelter from towering Southern Ocean swells behind the aptly named Breaksea Islands in Port Davey. Within a couple of hours and a few kilometres, we are drifting along the Old River off Bathurst Harbour where the water offers millpond reflections in the warm autumn sunshine. Such are the rapidly changing moods of this amazing wilderness.

The Old River cruise leads to a short walk and a patch of ancient rainforest dominated by a 1500-year-old Huon pine. A nursery of younger Huon pines thrives in this sheltered twist in the river which provides wet feet for these remarkable trees.

Highlights of the day include a visit to the grave of Critchley Parker, the 31-year-old son of a wealthy Melbourne family who had a dream of establishing the “new Jerusalem” at Port Davey. It was to be a new homeland for 50,000 Jewish refugees displaced during World War II. He set out to survey the shores under Mt Mackenzie but died in his sleeping bag about 54 days later, having run out of food.

The crew of five from the wreck of the 80-tonne three-masted schooner Lourah were a little luckier, thanks to the quick thinking of a young passenger named Harry Risby. Harry wrapped a loaf of bread and bag of oats in a blanket during their dramatic departure from the wreck.

The Lourah was on her maiden voyage, bound for Strahan with a load of timber, but ran into rocks during a wild storm at Mud Island in Port Davey on January 3, 1900. The four crew and Harry managed to escape in a small boat and find shelter in a cave which had been excavated for ochre by the local needwonnee people just inside Bathurst Channel. There they huddled for four days until a fishing vessel came to their rescue. Young Harry, whose descendants still live in Tasmania, was hailed a hero. A report in the Mercury on January 15, 1900, said: “This wreck again emphasises the need for telephonic communication with Port Davey.”

Thankfully, while the advent of satellite phones allows locals to communicate more freely, telephonic communication doesn’t extend to mobile coverage. It’s one of the true attractions of a visit there. It provides a rare reprieve from the hustle and bustle. You can’t help but relax, breathe in the fresh air and soak in the landscape.

Later in the trip we scale Mt Beattie, and the steady climb to the 267m summit is rewarded by amazing vistas south to Port Davey and north across Bathurst Harbour to the Western Arthur Ranges beyond. It’s a breathtaking sight.

It is this Port Davey landscape which has crept under the skin of award-winning artist Jennifer Riddle. She too keeps coming back. In particular she is attracted by the fascinating forms of the Celery Top Islands just inside the entrance to Bathurst Harbour. Untouched by fire, which has shaped the landscape of much of Tasmania’s southernmost wilderness, the small, heavily wooded islands are home to ancient trees and shrubs atop the rugged quartzite base.

“I’m a bit obsessed with the place,” says Riddle. “There’s something almost haunting about the islands and the story they tell in the landscape. The bonsaied trees, shaped by the wind, cling on for survival in the harsh but beautiful environment.”

Her impressive 1.8m x 1.8m entry in this year’s Glover Prize won the people’s choice award for the Mornington Peninsula-based painter. It’s the second time she’s won the people’s choice, picking up the same honour in 2017. So what is it about this isolated outpost that first caught her soul in 2015?

“My family and I had been coming to Tasmania and visiting wilderness areas for years, but I had never been to this pocket before. It’s a land locked by mountains and it’s like a window into another time. I feel like I have so much passion for the place and it translates into my work.”

The passion for Port Davey is shared by many, and none more so than those that live or have lived there. People like the legendary Charles Denison (Deny) King who lived at Melaleuca for 55 years until he “ran out of horsepower”, as the man himself put it shortly before his death in 1991. Peter and Greg have arranged a visit to Deny’s former home where he brought up two daughters, Mary and Janet, with wife Margaret. The home provides a glimpse into the past and has been immaculately maintained by his family.

Handcrafted chairs and a bed demonstrate Deny’s resourcefulness and skills. A cloud chart still hangs on the wall — used by Deny for 45 years as a volunteer observer for the Bureau of Meteorology. A cherished piano saved from bushfire and painstakingly brought to Port Davey in a boat, sits in the bedroom. The propeller from a plane (which nosedived into the Melaleuca mud while trying to take off in the days before the airstrip) forms a dramatic centrepiece on the mantle.

Peter recalls visiting Deny and sharing a cuppa. “You had to be careful where you put your feet, because there would be wrens and other small birds gathered around Deny as he sat at the table. While you were sitting there, yellow-throated honeyeaters would fly in and take a sample from the sugar bowl,” he says. “It has been such an honour to meet and spend time with him. Even back then I knew he was such a special person and held in such high regard.”

Deny was an enthusiastic naturalist and spent many years studying Port Davey’s plants, birds and animals. He is credited with identifying one of the world’s oldest and rarest plants — Lomatia tasmanica or King’s lomatia, also known as Kings holly. It only grows in South West Tasmania with 300 plants growing in a 1.2km stretch of wilderness from rootstock dating back 43,000 years. There is a small sample of the plant growing in the garden, which is still maintained by the family.

The wilderness is home to many animals, with Bennetts wallabies, wombats and spotted-tail quolls common in the area. There also is an abundance of birdlife from graceful black swans to tiny scrub tits and fairy wrens and large colonies of shearwaters. At one stage during our cruise out to the Breaksea Islands we spot a pair of sea eagles rising into the air. They are quickly joined by two, and then three others. The site of five of these majestic raptors is amazing, and an encouragement to bird watchers everywhere. Well, almost. There is a group of dedicated volunteers at Melaleuca who may not be so heartened by the sight.

Marg Cranney is one such volunteer who, for the past 14 years, has been returning to the far South-West with Wildcare to monitor the critically endangered orange-bellied parrot. Only about 300 birds exist on the planet, most in aviaries, with about 20 wild birds returning to Melaleuca to breed this summer and 36 baby OBPs now in the wild after a successful breeding season. We are lucky enough to enter one of the Melaleuca hides and watch as 11 juvenile parrots feed. They are expected to leave within days on their mighty migration north for the winter.

They’ll be drawn back again … along with the mutton birds, the tour guides, bushwalkers, birdwatchers, boaties and artists. And so will we.

Because when you leave this place of such peaceful isolation and rugged beauty you’re somehow changed. And as you fly back to Hobart and look down on the vastness of Port Davey, you yearn to get back there to be refreshed, delighted and inspired all over again.

Par Avion offers three-day, two-night Wilderness Camp experience includes flights, all meals and tours for $2495 per person. Six-hour day trips including lunch and flights start at $599 per person.

A seven-day yacht cruises including meals is offered by Hobart Yachts starting at $4950 per person.

Tasmanian Boat Charters offers 4, 5 and 7-day expeditions around Port Davy aboard the Odalisque which includes, flights to and from Melaleuca on-board chef and guides. From January-May. Trips range from $5000-$8800 per person.

Port Davey 7-day kayaking trips by Tasmanian Expeditions includes flights, meals and camping accommodation from $3295 per person.

Trek Tasmania offers seven-day guided walking tours to Port Davey covers 71km for $2495 per person. It also offers a nine-day South Coast hike covering 91km for $2695 per person.

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

Step back in time with modern comforts at hidden New Norfolk gem

Marking the 200th anniversary of its construction, the Woodbridge property has been restored into a small luxury hotel offering a five-star experience that cannot be missed.

Is this Hobart’s cutest historic property?

Lovingly restored from its 1857 origins, this South Hobart cottage oozes character and charm. Thanks to the retention of many original features guests are transported to 19th century Hobart