The mystery of ‘Rack Man’, tied to a crucifix and dumped in the Hawkesbury River

MARK Peterson felt a huge tug on his fishing net, but what he reeled in was no monster. It was the body of a man tied to a metal cross.

Lifestyle

Don't miss out on the headlines from Lifestyle. Followed categories will be added to My News.

JOURNALIST and author Justine Ford has spent years investigating Australia’s most baffling homicides and mysterious missing persons’ cases.

One of those cases, published in her new book Unsolved Australia, is that of ‘Rack Man’, a body found tied to a crucifix in Sydney’s Hawkesbury river in 1994. Twenty one years later police are still asking for your help to solve the mystery.

News.com.au has been given this exclusive extract.

***

It promised to be a bumper day at the market when an experienced fisherman felt a heavy tug on his net — enough to pull him back towards port.

But rather than a bounty of prawns or squid, the fisherman hauled in a most macabre catch of the day — the remains of a human body, tied to a rusting steel crucifix. It was a killer trawl.

On Thursday, 11 August 1994, Mark Peterson’s workday began like any other. He’d cruised up the Hawkesbury River, north of Sydney, until his boat the Lady Marion was bobbing calmly in the water just past Challenger Head.

But Mark’s peaceful day took its bizarre turn around midday when he dragged the cumbersome steel frame onto his deck. Attached to the frame were several plastic bags, and out of one poked a bone. Surely it was from an animal, he thought. But when Mark looked closer, he could see even more bones and realised his catch was even fishier than usual.

Immediately, Mark called the Broken Bay Water Police, who arrived just before lunchtime — not that anyone was feeling peckish. The Water Police escorted the Lady Marion back to Patonga Wharf, where an officer from the Gosford Physical Evidence Section made a preliminary examination of the remains, which she classified as human, not animal.

The next day, forensic pathologist Dr Chris Lawrence examined the remains more closely at the New South Wales Institute of Forensic Medicine in Glebe, better known as the city morgue. Dr Lawrence noted that the set of bones on the steel slab before him were ‘roughly anatomically arranged’.

He also inspected a quantity of soft tissue and adipocere, sometimes known as grave wax, a substance which forms underwater and preserves a person’s shape or features. He observed that the bony and soft tissue were wrapped in a long sheet of black plastic, and that two plastic bags had been used to cover the person’s head. Orange rope had been tied around the neck in a non-slip knot.

From the skull, Dr Lawrence determined that the remains belonged to a dark-haired caucasian man between twenty-one and forty-six years old who’d died from blunt force injuries to the head. The length of the dead man’s bones showed he was fairly short, about 163 centimetres tall, give or take three centimetres.

Dr Lawrence couldn’t tell, however, whether or not the man was dead before he was attached to the ghastly steel frame, which was made from a 1.82-metre length of flat metal onto which someone had welded two cylindrical solid metal bars. Between the bars, two pieces of reinforcing rod had been attached and bent into a restrictive L shape over the man’s body.

After wrapping him in plastic, the creator of this monstrosity — or a like-minded associate — had bound him with rope. If the embattled victim was still alive, any notion of escaping was dashed when his captor wrapped wire around his neck and torso.

“I would say as an investigator that it’s an unusual way to dispose of a person,” says Detective Chief Inspector John Lehmann from the New South Wales Unsolved Homicide Team. “And was this person attached to the frame and tortured before he was thrown in?” he wonders. It is a possibility that horrifies the veteran detective.

Identifying Rack Man has been the number one problem ever since the rusty steel frame and its grisly human cargo were hauled out of the water. “Until you identify the victim, you haven’t got a starting point,” John explains. “At least with a victim who has been identified you can look at who the person was and ask questions like: What was he doing? Who were his associates? Was he in trouble? Was he known to police, and if so, for what reasons?”

Victimology — the study of a victim and their associations — is crucial to the success of a homicide investigation. “The background of a person will tell you so much,” John reveals. “In this case, for example, was he a drug dealer? Did he owe people money? Knowing those things would open so many doors.”

At least science offered some clues. Forensic odontologist Dr Chris Griffiths examined the victim’s skull and teeth and concluded that his face might have been slightly misshapen. The man had no fillings and his first lower right molar had been removed, probably when he was very young.

Unfortunately, the water had washed away the dead man’s fingerprints, and his DNA sample was of such poor quality it couldn’t identify him either. But police don’t rule out that, with advances in technology, DNA will eventually name him.

Other clues to his identity were his clothes. He wore a medium sized polo shirt with the label ‘Everything Australian’. His large, dark-coloured tracksuit pants were branded ‘No Sweat’, and there was a packet of Benson & Hedges cigarettes and a pink lighter in his left pocket. He also wore a pair of ‘Sparrow’ brand blue and white striped underpants which were designed to fit an eighty-five centimetre waist.

The original investigators tracked down the shirt’s manufacturer, who gave them a general idea where the garment might have been purchased. “Police showed the shirt to the operations manager from “Everything Australian”, who indicated that the company used the logo on the shirt tag between 1982 and 1987,” John says. “She also indicated that during that period of time, the company had around twenty-three stores throughout Australia, mainly in New South Wales and Queensland.”

Determined to identify the man somehow, detectives travelled to Adelaide’s Forensic Science Centre where forensic biologist and specialist hair examiner Silvana Tridico put Rack Man’s dark strands under the microscope. She agreed that the hair appeared to have belonged to a caucasian man, and was able to add that he was possibly Mediterranean.

Forensic science was again used to tell the dead man’s story when police lugged the steel frame over to Emeritus Professor Donald Anderson at the University of Sydney. The professor removed two barnacles in order to assess their growth rate and thus determine how long the frame had been submerged in the water.

“It’s like entomology,” John explains. “You’re able to tell how a long a body has been there.” Professor Anderson concluded it had been underwater for less than a year, although he couldn’t entirely rule out a longer immersion time. The investigators’ next step was to try to find out what Rack Man had looked like before someone mercilessly bashed in his head and threw him in the river.

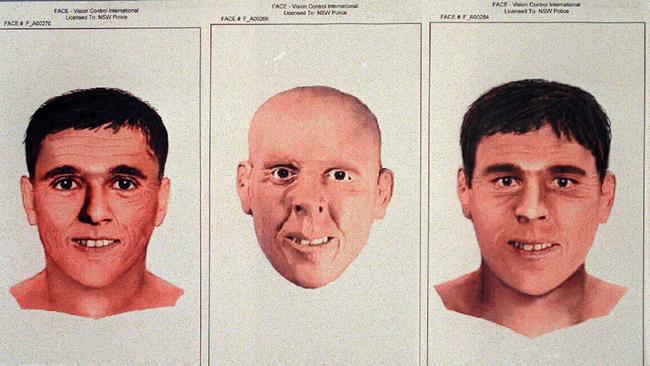

Sydney-based forensic anatomist Meiya Sutisno carried out a facial reconstruction of the victim’s skull when she was a student, under the supervision of forensic anthropologist Dr Denise Donlon.

Detective Senior Constable Phil Redman from the Physical Evidence Section then provided the investigators with a variety of computer-enhanced pictures of what Rack Man might have looked like. The facial reconstruction and the computer-enhanced images were broadcast on the news, in the papers, and on the TV crime show Australia’s Most Wanted.

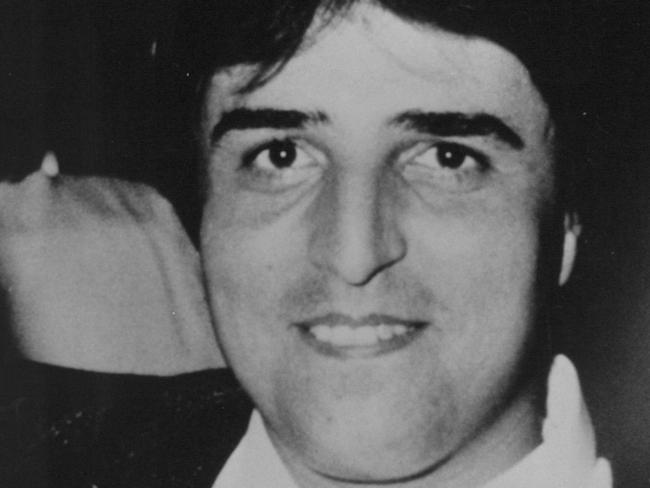

The public responded right away and names came in thick and fast. One member of the public said the victim could have been convicted drug dealer Joe Biviano, who was born in 1963 and had gone missing from the Sydney suburb of Drummoyne in December 1993. On face value, Joe fitted the bill: he was the right age, had dark hair, was of Mediterranean appearance, and 165 centimetres tall.

“Information was also received that he was similar in description to the facial reconstruction,” John says. Unfortunately, Joe’s dental records couldn’t be found, so the police, hoping Rack Man’s weak DNA sample might eventually provide them with an answer, asked Joe’s family for their help.

“A DNA sample was taken from a relative in 2005 but to this date it has not matched to the remains on hand,” John says.

Others suggested the victim was Greek businessman Peter Mitris, who was last seen on the mean streets of Kings Cross in April 1991. Police had previously received information that Peter had been bashed to death and his body dumped in the ocean off Sydney. But Peter was 182 centimetres tall, far taller than the man whose remains were found strapped to the steel frame and dumped in the Hawkesbury River. And according to his sister, Peter’s crooked teeth didn’t look anything like Rack Man’s.

There was also talk that the bones had belonged to Mr Renta-Kill himself, Christopher Dale Flannery, who’d disappeared in May 1985. But when Dr Chris Griffiths compared the alleged hit man’s dental records with Rack Man’s, they didn’t match.

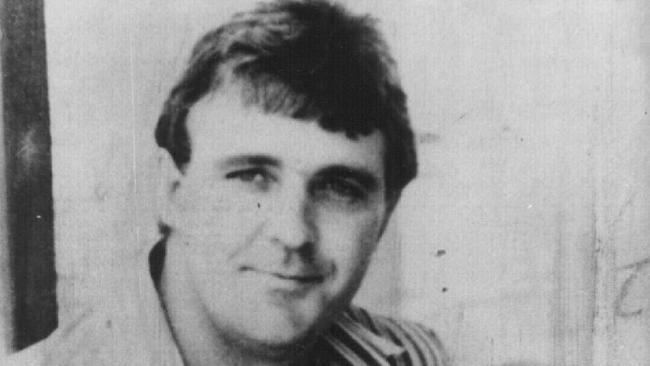

Then there was the possibility that the victim was Stephen Bryant, who told his friends James and Christine Nissen that he’d spend Christmas with them in Tucabia, near Grafton in northern New South Wales, but never turned up. Subsequent inquiries led police to suspect that Stephen may have been involved in a ‘drug rip-off’ which led to his demise.

The final possibility was that the remains were those of heavy gambler Matt Tancevski, whose live-in lover last saw him in January 1993 at Newtown in Sydney’s inner west. At the time of his disappearance, Matt had eighteen hundred dollars in cash on him, but it wasn’t unusual for him to withdraw large sums from the bank. It wasn’t unusual for him to travel to the Gold Coast on a gambling binge either, but he always came home a few days later. Just not this time.

With nothing to prove that Rack Man was Stephen Bryant or Matt Tancevski either, police continued to search for names. “The DNA database is always checking samples,” John says, explaining that it’s the job of the New South Wales Missing Persons Unit to collect DNA samples from the relatives of missing people, to match against unidentified remains. “But that hasn’t been successful with Rack Man to date,” he adds.

All these years later, police are wondering if the metal crucifix itself can help them solve this gruesome case.

“We’re looking for anything that’s identifiable about the components or the metal frame itself that might tell us where the components were manufactured or sold, or what type of industry they might have been used in. That may tell us a bit of information about the victim and possibly about the killer,” John says.

“Is the person involved in the murder or in disposing of the body involved in some sort of welding occupation, or are those materials available to him?” he asks. “Is he a metal worker or a builder, or is the victim possibly connected to that type of thing? You have to look at those kinds of things.”

The gangland-style disposal of the body strongly suggests the victim was involved in something unlawful which led to his nightmarish end. But what? “You do think of organised crime or something the victim may have been involved in,” John says. “A normal person would not expect to meet their demise like this, so we think that the victim was involved in some kind of criminal activity.”

Even so, what a way to go. “Whoever this person is, he’s someone’s son or husband or brother and it’s not just the actual victims of homicide who suffer — it’s their families,” John reminds us. “There is more than one victim.”

Today, the body of Rack Man still lies refrigerated at the morgue, waiting for someone to claim him and give him a proper burial. And even if he was an underworld player, he certainly didn’t deserve to die like this.

More than twenty years after Rack Man was dumped in Davy Jones’ locker, police believe that someone can still identify him, and even name his killer. It’s time to spill.

There is a $100,000 reward for information leading to the identification of Rack Man and the arrest and conviction of those responsible for his murder.

Unsolved Australia by Justine Ford is published by Macmillan, RRP $32.99. For information visit www.panmacmillan.com.au.

This extract was reproduced with permission.

Originally published as The mystery of ‘Rack Man’, tied to a crucifix and dumped in the Hawkesbury River