TasWeekend: Promises broken and myths busted

Artist Julie Gough is on a quest to bring Tasmania’s hidden history of the colonial frontier to light in the biggest exhibition of her career.

Lifestyle

Don't miss out on the headlines from Lifestyle. Followed categories will be added to My News.

JULIE Gough is an important artist. Don’t run and hide when you hear that. Leave that to Gough, who literally runs and hides sometimes. She’s not here to ram anything down your throat; she understands the power of suggestion and impact of quiet repetition. For many reasons — and heartbreak outweighs quirkiness 100 to 1 — there is no turning away from Gough’s work as she wades the murky shallows of white settlement on this ancient island to resurface stories of loss and atrocity.

The photography and video works in which she runs — We ran/I am, 2007 — and for which she hid — Observance, 2012 — are two pieces in a major exhibition of Gough’s artwork that will open at the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery next weekend.

It will span four galleries and a five-month run. Mona’s Dark Lab, the show’s major partner, will raise an ephemeral work on the Domain over Dark Mofo this month.

The TMAG show will include new site-specific works, key work from the artist’s 25-year, multi-disciplinary practice, and artworks and artefacts from the museum and gallery collections. Major institutions loaning works include the National Gallery of Australia. A public and educational program is in development. The exhibition is not only a career milestone for Gough, it comes at a time of reckoning in Tasmania.

Dr Mary Knights of TMAG is the curator of Julie Gough: Tense Past. She nominated Gough for the gallery’s biennial focus on a major Tasmanian artist.

“Julie is a very courageous artist whose work is powerful, conceptually and aesthetically, as she interrogates colonial history,” says Knights. “Her way of looking back to the early 19th century is so potent.

“It’s the history that we need to acknowledge, comprehend and come to terms with in order to work out how we should live well in this place. I think Tasmanian people are ready to listen.

“There have been a lot of very narrow colonial stories expressed through the collections in this museum over the last 180 years. It’s so important to have people like Julie come in, research the collections, look at the objects, read between the lines and describe, discuss and contextualise the artefacts and artworks from very different perspectives.

“Julie brings to bear a perspective of Tasmanian Aboriginal people. The overarching curatorial premise reflects Julie’s focus on uncovering and re-presenting subsumed and often conflicting histories, often referring to her own family’s experience as Tasmanian Aboriginal people.”

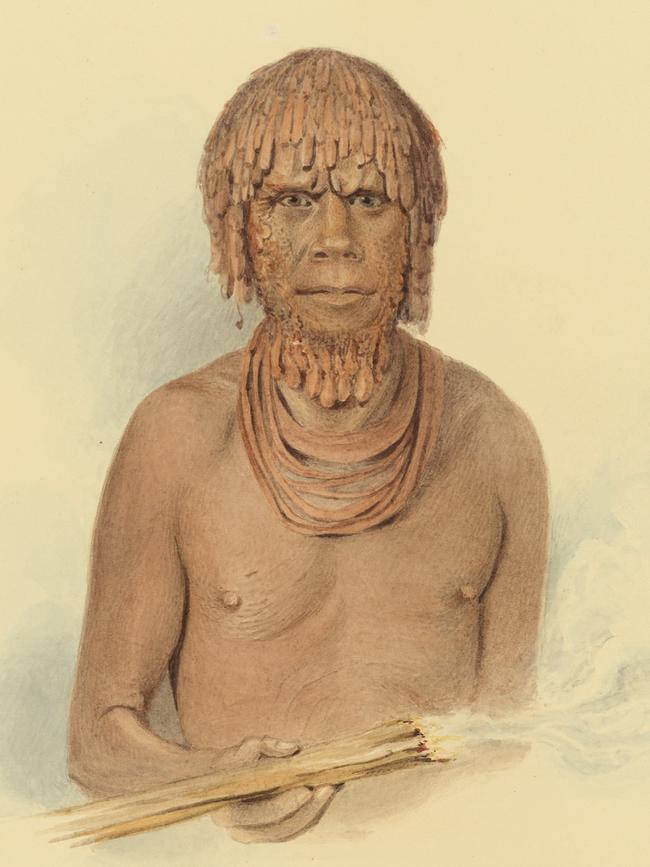

Gough is descended from Dalrymple Briggs, a granddaughter of revered clan leader and warrior Mannalargenna, from whom many Tasmanian Aborigines can trace their lineage. Dalrymple’s mother was Woretemoeteyenner, who was kidnapped from the North-East in her early teens and became a “wife” of sealer George Briggs, with whom she lived on various Bass Strait islands and had at least four children.

Dalrymple lived part of her childhood with a white couple in northern Tasmania. After they died, she lived on the colonial frontier at Quamby Bluff, with a convict partner and two children. She went on to have at least 13 children in total, spending most of her life around Latrobe near Devonport. Like quite a few Tasmanian Aboriginal people, Gough’s maternal grandmother moved to Victoria in the Great Depression seeking work.

Gough was born in Victoria in 1965. She grew up in Melbourne and Western Australia, moving to Tasmania to live in 1993. Her parents and brother followed her to the state one by one. They have lots of extended family still around Latrobe.

Colonial frontier history has consumed Gough for more than 20 years. A curator, writer, university lecturer and Doctor of Philosophy in visual arts, she says it was the desire to understand the lives of her ancestors that brought her to art. “I grew up with a history of being absent from Tasmania, this mythical homeland we’d never lived in on Mum’s side, and also a whole exiled from Scotland thing, too, as my Dad’s Scottish.

“Growing up in Melbourne we were isolated from the Tasmanian Aboriginal community, as part of a diaspora on the mainland. Coming back as a person that grew up elsewhere leaves me in a space that I don’t mind, but it took a while to get used to, which is as an outsider looking in. That’s my reality.

“When I moved here in late 1993, at that point I felt ‘I’m home’, but it’s not as easy as that. I missed two decades of really important political activity, so this in a sense is my political activity, creating these artworks.”

Final show preparations are getting under way when we meet in an upstairs office at TMAG. Questions hover about the suitability of the setting, for not just our interview but the show itself, as the sliding doors at the waterfront staff entrance on Davey St seal us into the vast old colonial bastion.

Gough gets it, of course, the wild incongruity. In that sense, TMAG is an ideal venue for her show. This intersection of colonial and Aboriginal Tasmania is the heart of her work. What better place than from within to challenge the dominant colonial narrative? This show continues the institution’s recent support for the critical examination of recorded history through insightfully curated shows. These include last year’s The National Picture: The Art of Tasmania’s Black War curated by academics Tim Bonyhady and Greg Lehman, which was first shown in Canberra. Julie Gough: Tense Past will be the biggest such solo exhibition TMAG has mounted on these themes.

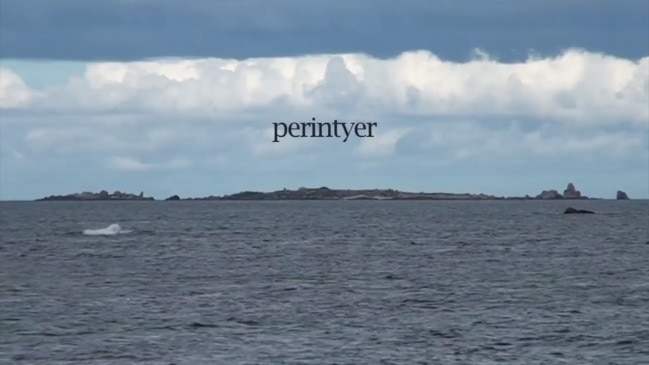

Revisiting specific places and events that her ancestors experienced offers Gough “a sense of return”, she wrote in an introduction to the book Fugitive History: The Art of Julie Gough (which will be available for purchase). One of these was Friendly Mission leader George Augustus Robinson’s August 1831 promise to Mannalargenna, pledged near Swan Island in the North-East, that if the Aboriginal people put down their spears and surrendered, they could stay on their traditional lands and be protected by “a good white man”. Instead, they were sent to Flinders Island. Mannalargenna spent the rest of his life there in captivity.

“Making art about the promise to my ancestor Mannalargenna by George Augustus Robinson, following my stay at the place where the promise occurred, was critical to the direction my work has taken,” Gough says.

“I am obsessed with bringing hidden histories to light. It’s a lifetime’s work to really understand those first 50 years.”

She combs over historical documents as she tries to piece together the life histories of individual people. This biographical accumulation is especially poignant in the Dark Mofo element of the exhibition, in which posters of 185 children will be tied to trees in a grove in the Queen’s Domain. She describes Missing or Dead as a genocidal constellation of children.

It is the result of 20 years’ ongoing research into the lives of Aboriginal children who were living with colonists. “I am trying to work out what happened to them all,” says Gough, who once considered becoming a librarian, before studying archaeology and art. “One boy had three names. They moved them around, like ‘send them back to the dogs’ home’. It is a complete exercise of accounting for what is missing. Everything is a bit like that: What the hell happened at a particular place?”

Tying the posters to trees recalls Governor Arthur’s 1828-1830 distribution of the Proclamation to the Aborigines, which attempted to explain in pictures the idea of equality in punishment for violence under the law. Some picture boards were fixed to trees and only seven are known to have survived around the world, one of which will be in the TMAG exhibition.

Missing or Dead will be mounted in a forest grove near the old Beaumaris Zoo, opening by night for torchlit viewing as well as by day.

Gough has drawn on imagery from the Proclamation panel in previous work, including Missing, 2011, in which she responds to a well-known Midland Highway steel sculpture project by two local artists.

This series of larger than life-size silhouettes placed either side of the highway on denuded farm hillsides between Kempton and Tunbridge will be familiar to many readers. The 16 Shadows of the Past sculptures show early white settlers in a range of activities. There’s a bushranger, surveyor, hangman, shepherd with his flock and dog, policeman wheeling a drunk man in a barrow and so on. The extinct native emu and thylacine get a look in, but the first people of the island do not.

A Southern Midlands Council interpretation document for the series describes Van Diemen’s Land as “first and foremost a British military outpost”. A research footnote adds: “This material is drawn from records kept meticulously by the colonial authorities. There is no such comprehensive record of Aboriginal voices of the time. We can try to imagine the Aboriginal peoples’ experiences. It is likely they would tell a very different story of these events.”

Cultural appropriation is a legitimate concern that scares off plenty of non-indigenous artists from referencing Aboriginal Australia, but the result can be further historical obscurity. It can come across as casual erasure of more than 50,000 years of previous occupancy. It feels wrong to Gough. “I don’t want to be rude to the person who’s done all those animals and convicts, but it’s weird.”

In 2011, Gough made plywood prototypes of two panels she wanted to add to the series, and exhibited them at Bett Gallery, her long-time Tasmanian gallery. One silhouette drawn from the Proclamation panel showed an Aboriginal man spearing a male white settler and the other showed a white settler shooting an Aboriginal man. Gough’s prototypes were sold to an American collector before she had a chance to have them made in metal. Missing will be missing from this show, but she still thinks about the incomplete project. Watch this space.

Over four decades to the 1830s, most of the Tasmanian Aboriginal population, believed to be about 5000 men, women and children, disappeared, mostly unaccounted for, with the remaining people mostly living on exile in Bass Strait islands.

Julie Gough: Tense Past addresses that absence. The Gathering, a multi-media installation, is a major piece. A film element of it shows colonial property gates filmed on slow drives-by (with Gough’s husband, Koenraad Goossens, sometimes on driving duty while she holds the camera).

In front of the projection sits a large colonial table laid with 28 small crosses, each with a small stone. The room is carpeted in a specially commissioned design, plush and subversive. As viewers sit on antique chairs around the table, lulled by the room’s classic ambience, the slow burn begins and a fuller story dawns. Each stone was collected from the gateway of a colonial property whose then-owners participated in the Black Line campaign, an all-out assault in 1830 that aimed to force Aboriginal people off their homelands and onto the Tasman Peninsula. The film finishes with a roll call of land grantees who signed letters of thanks to Governor Arthur for his removal of Aborigines.

“I am passionate about the possibility of what may appear initially benign or without potential [for artistic expression],” says Gough. “What do all these names of colonial properties mean? Put a series of them together and you come up with an understanding of the enormity of the exile of Aboriginal people and the removal of Aboriginal people from country. “These names that were put there in the 1820s or 1830 may look like an appealing name on a fencepost, but they are the colonial project, and they are still there and it’s still strong.

“How do you have the conversation [with landholders] about what those 3000 acres meant to an aboriginal family or band or tribe? How do we navigate that space now?”

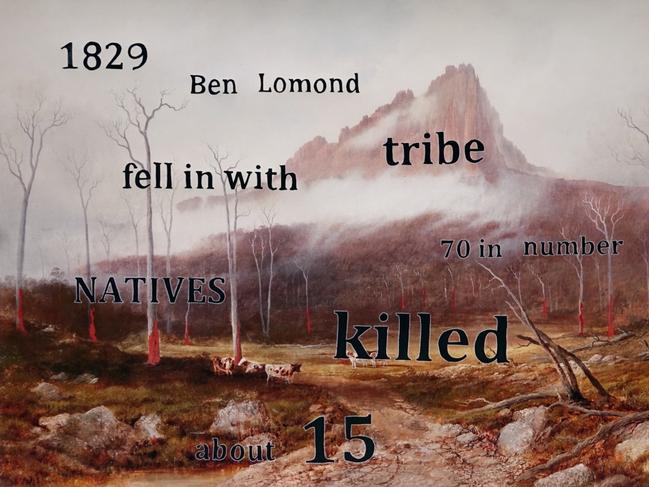

The Black Line is the focus of one gallery. In another, Gough brings to light unpublished, untranscribed official records full of details of life at the time. This space also holds The Impossible Return, a still-life composition of remnant objects, the title alluding to her pursuit of an elusive past. In Hunting Ground (Pastoral), 2016-2017, Gough records sites of indigenous massacre. In the 2008 piece Some Tasmanian Aboriginal Children living with non-Aboriginal people before 1840, Gough has poker-worked children’s names onto unfinished spears.

Gough spent her first decade in Tasmania mostly working inside, obsessively following a paper trail and then letting the imaginative process happen. Then she moved some of her practice outdoors, experimenting with stills photography.

In We ran/I am, 2007 she was photographed running as fast as she could in places of significance in the Black Line campaign. It was not a re-enactment as such, she says, though she wore a pair of trousers custom-made to resemble the original pants dispensed to Aboriginal men.

“It is me alive, saying ‘we got through this, you bastards, we can run here now’. So there’s a kind of joy in that work for me, as well as the oppression, as well as the ridiculousness ... I don’t run, I’m unfit, all that.”

Discovering video was a breakthrough. “I love video so much because it gets me out of my house,” she says. “And that’s when the ideas come for the works, rather than in the lounge room.

“The video could also be connected to the fact I’ve filled my house with so much stuff I don’t have any space to make art anymore. So I make video. The back of my van is my studio, with my tools and my mattress.”

Lately, feeling a bit flush, she has spent some of her artist fees on accommodation. She enjoys the comfort, but she’s not about to stop sleeping in the van.

“In the van, you feel vulnerable, and that takes you more into the place of history, so it’s better. What’s going to creep in through this window from the essence of this place that’s not going to creep into a cottage five kilometres away? The truth is out there, isn’t it.”

Gough is not into heavy-handed messaging. Intrusive interpretation panels in nature are a bugbear. On a recent trip to Mt Field National Park, she took the short Tall Trees Walk. “Along it there were all these completely inane and entirely annoying interpretation panels that say things like ‘Look at the tall trees. Immerse yourself and enjoy’. Giant panels. I was like, ‘Oh my God, Parks need to stop doing this’.

“This stuff reinforces to me to be really careful. There’s a really fine line. I like evidence, I like information, I like to share something that brings us a step closer to understanding, but not for the sake of littering.

“That’s what happens out there in this world of interpretation. I try to think of different ways to express. It’s tricky.

“When I was in art school, there was always this didactic conversation: how close can you go without going over the edge and ruining it.

“The works that haven’t gone too far are the works that have survived. The others evaporate or you rework them. The longer you make art, the more you don’t miss the mark.”

Repetition, with its cumulative and hypnotic power, is one of her devices. Observance, the concluding video, is about trespass, says Gough. She made the film over four years of occasional camping at Tebrikunna, her maternal country in the North-East. Again and again, she secretly filmed eco-tourists walking the Bay of Fires. One day she was found hiding in the dunes by a group. “That was pretty embarrassing,” she says.

She describes her film as a frustrated response to get back to the essence on country while being frequently interrupted by tourists. In their clockwork procession along the beaches, she says they “remind and re-enact the original invasion”.

“People are sleepwalking along the beach,” she says. “I find it interesting. It’s not a bushwalk, it’s this liminal zone. It’s not land or sea, it’s a way of being safe in nature, on that hard sand. I think about what a crazy world it is we live in now for people to spend thousands of dollars to walk on sand for a few days.

“In my film is one bit from the last day where people start running up and down this high dune and doing this thing like a joy dance. I realised, zooming, zooming, ‘Oh my God, they are trying to get reception on their phones’.”

She admits she’s done “weird” things there, too. “I’ve gone out at night and stood on my car bonnet to phone the husband in Hobart. I’ve got to be careful it’s not too ‘them and us’, because we are all in it together nowadays.”

This brings us to National Reconciliation Week, which finishes on Monday. Its theme this year is “Grounded in Truth. Walk Together With Courage”. In some way, Gough is not quite ready to walk the walk. She says we need to come to terms with our history before we can reconcile.

“There is much left to be uncovered and shared. I am not in the space of reconciliation until we ‘concile’. The middle ground hasn’t been reached yet between the cultures in Tasmania. The last 200 years were silent.

“People have leapt into this ‘oh, let’s reconcile’ and I’ve gone ‘wait a minute, nobody knows what needs to be reconciled, what needs to be forgiven’.

“The majority of people want to jump to the end, to the last songs in the album. No, we haven’t done the hard work together. We don’t know who’s missing, who’s dead, who did what or who needs to apologise on behalf of their family, even though they don’t want to.

“Stories and bringing objects from places and recreating a narrative about them can go a long way in helping us all understand our place here on this island and what our ancestors were responsible for, good and bad.

“For me, this work is about linking the history — oral history, recorded archival history — with the living population and with place. And right now they are very segregated from each other.

“I want us to find each other, but not so we can hold hands yet. There are people who just want to walk the bridge of joy together straightaway.

“I don’t want to have to spear them, but I do want to talk it through first.”

Julie Gough: Tense Past opens at the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery in Hobart on June 7. The exhibition will run until November 3. A new ephemeral work, Missing or Dead, will be shown on the Queen’s Domain over Dark Mofo from Friday June 14 to Sunday June 16 (5–10pm) and Wednesday June 19 to Sunday June 23 (5–10pm).