TasWeekend: Manuscript sheds light on Tasmanian career criminal’s run-ins with Ned Kelly and others

A newly published manuscript sheds light on the fascinating life of a career criminal of the 1800s, James Mitchell, who crossed paths with Ned Kelly and saw Sir William and Lady Don perform on stage at the Theatre Royal.

Lifestyle

Don't miss out on the headlines from Lifestyle. Followed categories will be added to My News.

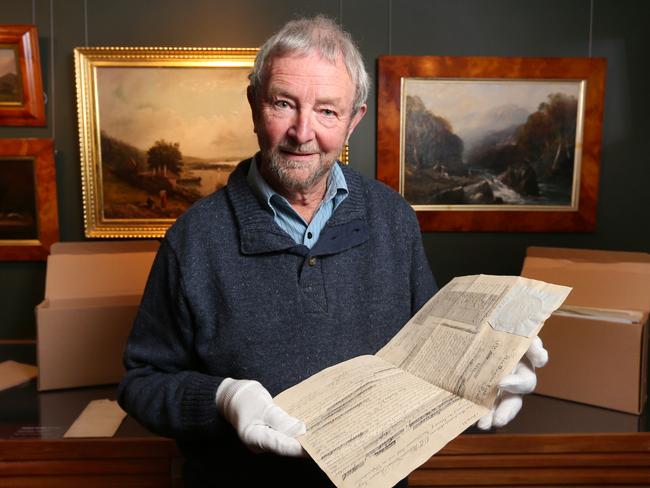

HISTORICAL researcher Brian Rieusset could not believe his eyes when he first read the 100-year-old transcript of the life of habitual criminal James Mitchell. The account given by the then-79-year-old prisoner, dictated to the superintendent of the old Launceston Gaol in 1919, was replete with such amazing tales and run-ins with prominent figures that Rieusset initially deemed it too good to possibly be true.

But upon further research of his own, Rieusset realised that while some of the details were muddled, much of this elderly criminal’s story appeared to match actual historical events and records. If James Mitchell’s account is to be believed, he might be Tasmania’s equivalent of Forrest Gump, finding himself somehow present at some of the most interesting points in our region’s history.

He recounts crossing paths with Ned Kelly, serving in the Royal Navy at one of the most humiliating British defeats of the New Zealand Wars, being flogged by the man who hanged Ned Kelly, seeing Sir William and Lady Don on stage at the Theatre Royal, and growing up surrounded by convicts in the streets of Hobart Town, finally dying in Tasmania in 1933.

Perhaps more surprising is that Rieusset, a former curator of Hobart’s Penitentiary Chapel Historic Site and a seasoned authority on all things convict-related around Hobart, had never come across Mitchell’s name before.

“I’d never heard of him. It was so strange,” 77-year-old Rieusset says. “When my friend gave me the manuscript I thought it must have been made up. I waited a while and I read through it again and it started to become clear to me that while he had a few names and dates mixed up, which is unsurprising for a bloke his age, a lot of it actually checked out.

“One of the tales he told was about a murder that took place at New Norfolk and the only witness was, as he described it, a black boy up a tree.

“As it so happened, I recognised the description of this incident as I’d written something about it myself. I knew that there was a murder that took place in 1845 where the witness was a 12-year-old Hawaiian boy who was up a tree at the time.”

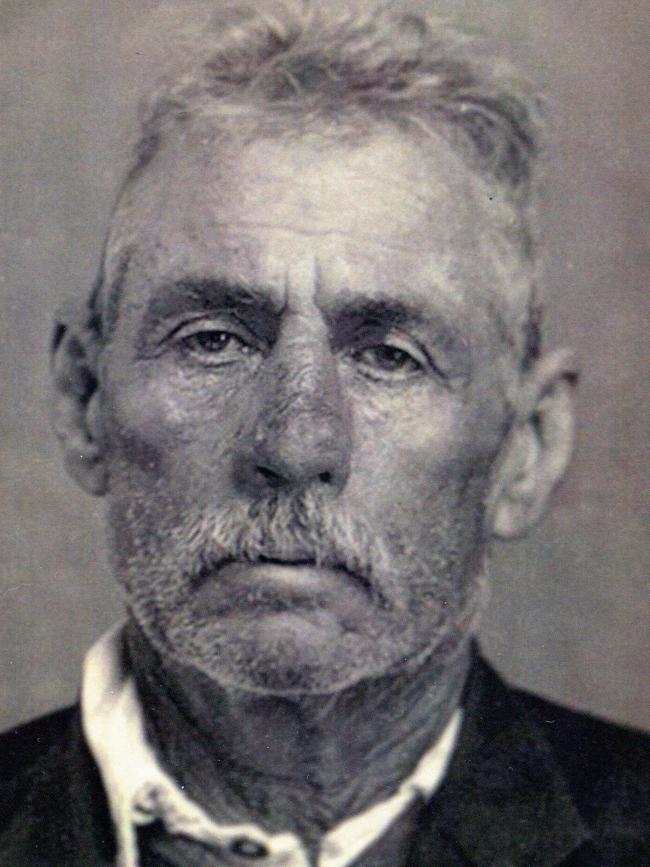

Excited that Mitchell’s story might hold water after all, Rieusset started cross-referencing it with every historical source he could find and, sure enough, a full and rich picture of James Mitchell began to materialise out of the muddle of aliases, mugshots and newspaper reports.

By the time Mitchell dictated his story to Launceston Gaol Superintendent Charles Leofwyn Willes, he was an old man who had been in and out of prison for petty offences for most of his life. But Willes, who had a penchant for collecting stories and artefacts from Tasmania’s earliest days, recognised there was something remarkable about this recidivist criminal’s life story. The 30 handwritten pages he produced from his chats with Mitchell now provide a fascinating first-hand snapshot of life in Tasmania from the time of convict transportation through to Federation and into the 1920s and 1930s.

That manuscript was passed down to Willes’s grandson, Wilfred Willes, who still lives in Launceston.

“It might be 100 years old, but it is in such amazing condition that it looks like it was written yesterday,” Rieusset says. “Wilf said he wanted me to have it, that it was time for people to see it. And I knew this story had to be written, even if it was the story of a career criminal. It was too important and he was too fascinating a character.”

Rieusset has turned that manuscript into a book, You Can’t Hang Me For It: The Life of James Mitchell.

Right from his birth, mystery and inconsistency starts to swirl around Mitchell’s life. But as near as Rieusset has been able to tell, Mitchell was, somewhat ironically, born in a house just across the road from the main gates of the Hobart Penitentiary, on Campbell St, around 1839.

James Mitchell was almost certainly not his birth name, but Rieusset believes he was born to a Hobart whaler and his wife. Mitchell’s mother died eight months after he was born and, when Mitchell was five, he was adopted, possibly unofficially by an emancipated convict couple living at Longford.

The family later moved to Hobart where Mitchell recalled being a young boy and seeing the convicts walking in chained groups through the streets, and he would occasionally loiter in places where the chain gangs were working, trying to give tobacco to the convicts.

His first job was cleaning at the Theatre Royal, where he saw some of the theatrical luminaries of the time, including Sir William and Lady Don. In 1958 he was employed as a labourer tearing down the old Government House in Macquarie St, which was being replaced with the present building on the Domain.

He also recalled the infamous fire that gutted Cat & Fiddle Alley, describing locals using cradles to sift through the ashes and rubble looking for gold from a jewellery store that was destroyed in the blaze.

In his 20s, around 1862, Mitchell lied about his age and joined the Royal Navy when the HMS Fawn was moored in Hobart taking on supplies and recruiting crew for a surveying mission in local waters. Having kept his nose relatively clean for most of his youth, Mitchell got his first taste of more serious trouble when he was caught and reprimanded for deserting the ship, before it had even left Hobart.

Following its surveying work, HMS Fawn joined a number of other British warships to take part in the New Zealand Wars, an ongoing fight between the native Maori and the colonising British. In 1864 Mitchell was part of the task force that attacked Gate Pa during the Tauranga Campaign.

The Maori were frequently underestimated by the Europeans and, despite having overwhelming numbers in their favour, the British frequently suffered disproportionately high losses at the hands of their resourceful opponents.

At Gate Pa, the Maori had constructed a fortification, or Pa, that was able to withstand an entire day’s artillery bombardment. In the late afternoon, confident that the Maori had been wiped out, a detachment of British soldiers stormed the Pa, led by several of the group’s top-ranking officers. It was a trap and, as the Maori ambushed and quickly dispatched the invaders, the rest of the British force found itself virtually without leadership, and beat a hasty retreat.

“When the British got up the courage to go back in, the Maoris had all gone,” Rieusset says. “The Maori regard Gate Pa as a great victory but the British basically never spoke about it afterwards.”

Following his naval service, Mitchell ended up in Melbourne, where his life of crime suddenly took off, racking up many years in Victorian prisons. During his life in Melbourne he was a real menace,” Rieusset says. “He was involved in several gangs, he was living with prostitutes, and he was in a labour gang with Ned Kelly while he was in gaol there. “At the time prisoners were being put to work splitting stone to help build a gun battery to protect Melbourne, and he and Ned were in the same detail. The way he tells it he became quite close to the Kellys and talks about visiting their family home.

“When he was talking to Willes, he was able to verbally recite a poem written about the Kellys. He still had it in his memory, which is quite surprising. Considering his age he had a brilliant memory for events that happened so long ago.

“For most of his life he was committing strings of really petty crimes but while he was in Melbourne he was a thug. He got an eight-year sentence for being in a fight with a bloke and he got 60 lashes given to him by Elijah Upjohn, also an ex-Tasmanian convict, who also went on to be Ned Kelly’s executioner.”

Somewhere around the mid-1890s, and following many years spent in and out of Victorian prisons, Mitchell found his way back to Tasmania, settling first in Devonport and later in Launceston, where he had a home in Earl St, a wife, Ada, and two children. Naturally enough for Mitchell, trouble followed close behind.

“That Earl St house burnt down under suspicious circumstances and Mitchell was charged with arson,” Rieusset says. “Luckily for him the only vital evidence came from a known drunkard, so the charges were dropped.”

Seemingly unable to control his impulses to steal anything that wasn’t nailed down, Mitchell continued to spend much of his life back in Tasmania in and out of prison, even being transferred between Hobart and Launceston. He was so institutionalised that he almost seemed to be more at home inside the walls of a gaol than out in the free world.

In 1915, aged 75, he was eventually sent to the New Town Infirmary at St John’s Church but, since that facility did not lock him inside, he frequently absconded and spent a lot of his time loitering around the nearby New Town School chasing the children for fun.

His regular escapades outside of the infirmary saw him incarcerated variously in the Launceston and Hobart gaols, and when his behaviour became too much for the New Town infirmary and prison was no longer considered appropriate, an elderly Mitchell was sent to the Mental Diseases Hospital at New Norfolk, where he lived out the rest of his days.

“There are plenty of detailed records from the Asylum,” Rieusset says. “The staff there referred to him as ‘the old dement’ and he had a tendency to fight and kick anyone who came near him. There was a comment in one of the documents along the lines of ‘why is he still alive?’.”

Longevity was certainly one of Mitchell’s gifts. He died in 1933, at the age of 94, and was buried at New Norfolk, although the exact location of his grave is unknown.

Rieusset’s book includes excerpts taken directly from Willes’ manuscript, interspersed with Rieusset’s own interpretations and clarifications, drawn from his own research, to either authenticate or debunk sections of Mitchell’s colourful account.

Comparing Mitchell’s words side-by-side with the established historical facts makes for compelling reading, a kind of case study in how historical truth can lurk behind even the most outlandish of biographies and the honest failings of human memory.

“James was a fascinating character. I feel like I really know him now, and I would love to have met him and asked him more questions,” Rieusset says.

“Basically, when he had a job he was quite OK and lived well. When he was in gaol he also tended to be pretty well behaved, as well. But if he was out of a job and needed money or the kids needed new boots or something, he would just walk through streets of Launceston, where the shops would have their wares on display out front, and grab a pair of boots and keep walking.

“But he never got away with it. He was so well known, and he was so frequently in the paper for crimes he’d committed, that everyone knew him. So he was always spotted, reported, arrested, charged, and then back into gaol for another month.

“He was once caught walking down the street with a goose under his arm just before Christmas. He’d stolen it. And he didn’t even bother hiding it. He was a true recidivist. In total he spent more than 30 years of his life in gaol, around 11,000 days.”

Charles Leofwyn Willes used to write articles for magazines about historical Tasmania and, as a prison superintendent, he also amassed quite a considerable collection of convict memorabilia and artefacts, most of which is now held at the Queen Victoria Museum.

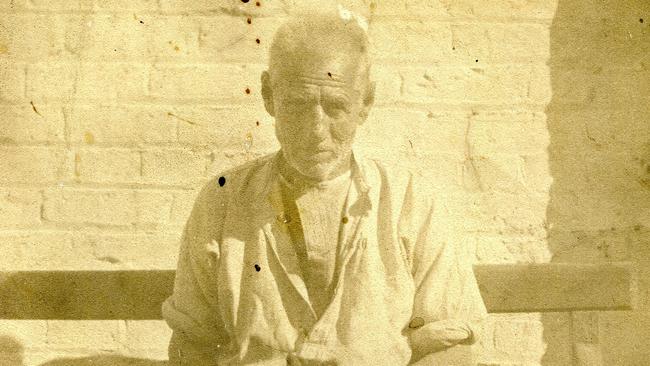

Also in his collection is a photo of James Mitchell, taken in 1919, as the old prisoner sits on a wooden bench in the sun, inside the walls of the Old Launceston Gaol, holding a kitten in his lap. This photo was taken by Willes himself around the same time as he was recording Mitchell’s life story.

“There absolutely are other documents like this out there, family stories that someone wrote down once, hidden away in private collections, and many of them may never see the light of day,” Rieusset says. “But I know of other people who are writing similar stories to this one at the moment. It is surprising how many are out there. Tasmania is so rich in that regard.”

You Can’t Hang Me For It: The Life of James Mitchell, by Brian Rieusset and Charles Leofwyn Willes, is on sale now in bookstores statewide for $29.95