TasWeekend: Fashion designer’s journey to Hill and back

FASHION designer Alannah Hill overcame a traumatic childhood by reinventing herself through clothes, and now she is reinventing herself again and sharing the story of her darkest days.

Lifestyle

Don't miss out on the headlines from Lifestyle. Followed categories will be added to My News.

“IT’S like I’m a movie star,” says Alannah Hill. The dethroned fashion designer and freshly minted author is sitting pretty at a swish Sydney hotel suite on a promotional tour for her memoir. And she’s feeling a bit spoilt and chuffed about it. She is dressed for the occasion, of course – Alannah Hill is always dressed for the occasion – in a floral-print silk dress with lace trim, sequined cardigan, jewelled platform shoes worn with black ankle socks sporting cream love hearts and a big pink pansy in her teased hair.

“I’m not, though, I’m not a movie star,” she adds. “I’m a little mongrel bastard.”

She’s joking, sort of. That’s the way conversation rolls with Hill, who ran away to Melbourne with eight suitcases of costumes as a traumatised Tasmanian teenager in 1979 and went on to become one of the country’s most celebrated fashion designers.

She would pluck names for her ultra-feminine and theatrical creations from the litany of her mother’s withering put-downs – “Nobody likes you, dear”, “You can’t sew”, “Edward is walking all over you, dear” and so on. She flew first class to London, Paris, New York and Tokyo selling her label, which was stocked in big-name department stores and a string of stand-alone boutiques. She lived in plush homes and her sherbet-coloured diary was full of dinner invitations, VIP tickets and fancy openings. She kept coming back to Tasmania twice a year, though, throughout the glory days, to see if she could finally win her father’s attention and her mother’s approval.

Now, after a tumultuous period in which she lost her job and the right to use her name on designs, she is back. This time, she may not have to climb and climb and climb, but this time, she hopes, her incarnation as a writer of astonishing candour will bring her some peace.

We have been talking for only a few minutes when Hill, 55, begins to weep, saying her brother Mark died three weeks ago and she did not attend his send-off on the North-West Coast. “I was advised it would be better for everyone if I didn’t attend my brother’s funeral and wake at Heybridge,” she says, blaming her decision to write the memoir for her exclusion. Though gutted, she stands by her right to tell her story. She says she was writing it in her head for 30 years and waited until both her parents were dead to put it on paper. “It came to a point where I couldn’t hold this back any longer.”

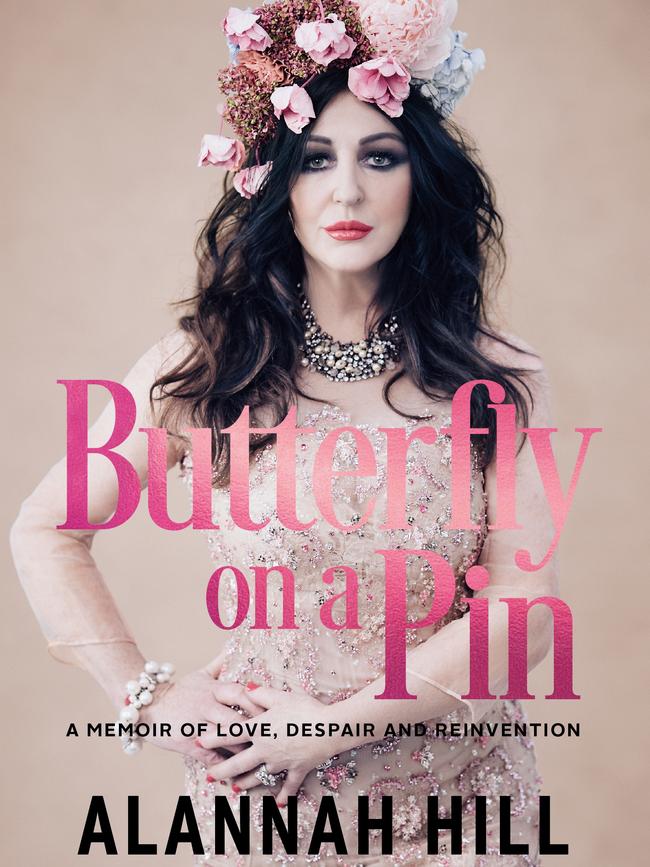

Butterfly on a Pin: A Memoir of Love, Despair and Reinvention has been out for a week when we speak. Hill is shocked when she sees it on bookstore shelves. “It’s confronting and alarming, and I have thought, ‘What have I done?’” she says. “It takes a lot of nerve to write a memoir. But it’s out of my control now.” She is trying not to fret and instead embrace the love coming her way from readers, particularly women at launch events and readings. “When I’ve been doing readings from the book, it gives me such validation,” she says. “No one listened to me when I was small. It is the comfort of strangers that has pulled me through, people coming up and telling me they love my clothing and they love my book. Many of the girls at a signing yesterday were like me – struggling, paddling beneath the surface, keeping secrets. They were crying. I was crying.”

The book is already creating a buzz, and not just because of Hill’s celebrity status. There is nothing shiny or superficial about this book. Her allegations of family violence, incest and other sexual abuse are harrowing. The first section, which paints a bleak picture of her childhood in Tasmania, is unforgettably powerful, with a voice and energy all of its own. She can really write (… and write – she says her editors had to cull 250,000 words from her manuscript).

Hill says, again possibly joking (it can be hard to tell), she hopes she will appear on the front page of the Mercury with our interview. Her mother, she says, never missed an opportunity to tell her when the Mercury had allegedly ignored her, so prominent coverage would be a bittersweet little victory. Like many of Hill’s fast-flowing stories and the book itself, the anecdote has a tragi-comedic dimension and her “apocalyptically negative” mother and their fraught relationship at its heart.

“The day my mother attempted to kill herself was not like any other day I’d known.” With these opening words, Butterfly’s painful flight is launched. “I was five years old. I remember the darkening clouds gathering in the foothills of the small ghost town, a ghost town where my family lived, a ghost town in Tasmania called Geeveston.

“I was desperately frightened … All we could do was rock back and forth, eating our honey sandwiches, waiting for the gigantic stranger, who was often seen glowering from corners or hurling raging aggression after drinking in the local pub. The stranger was my father… “[As my mother lay there] I wanted to die. I wanted the whole world to die. My eyes were blurred from tears and I heard him shouting at my mum. ‘For God’s sake, Aileen. This again! Jesus, Mary and Joseph, Aileen, what the f--- do you want?’

“I knew even then what my mother wanted. I knew it and I never spoke up. I wondered why my father couldn’t see it for himself. The truth is that my mother, over a period of 45 years, was almost sent mad by my father’s dismissal of her, and his own unhappiness, which, like the plague, spread death of one kind or another at a rate of a mile or more a day.”

Later, on her visits to Tasmania, Hill’s mother would often bring up the suicide attempt.

“You do realise I was almost DEAD, don’t you, Lan? What a dreadful man I married – a heathen, a philandering liar with insipid eyes. NO, I don’t know why he didn’t want you, Lan, I don’t know why he wouldn’t look at you. You were such a plain little thing. No personality, dear, you didn’t have a speck of personality. Not a SPECK!”

Now, that’s an ear for dialogue. Again and again in conversation, Hill breaks into mimicking her dry-witted, drawling mother and you can almost see the two cigarettes simultaneously aglow in the older woman’s hands as she engages in what was apparently her favourite sport, dragging others down. It’s wickedly funny as Hill takes her off, but there were terrible days with no light.

One of these was on a June morning in 1968. Six-year-old Hill and her seven-year-old sister were fighting over a rag doll the author had found in a puddle a few days earlier. She had not yet named the doll – neither Velvet, Chenille, Gypsy Girl Doll Dead nor her own name felt right – but she was prepared to fight hard to keep Shadow Doll, as she had dubbed the grubby toy until the perfect name landed. It was as if neither sister “could live unless we held that doll” and they yanked it apart in their tussle as their mother yelled at them to stop. Then their father appeared.

“‘Get those mongrel bastards out of my sight, Aileen. I told you to keep them quiet’,” she writes. “My mother flew through the air and threw both of us against the wall of the kitchen. Mum slipped on Shadow Doll and severed its head. My sister’s arm cracked as she hit the wall … Her little wrist flopped, her arm stopped moving. I saw her pain so clearly, her face tight with an indescribable look of fear …

“I spied my broken Shadow Doll lying on the ground, the cottonwool stuffing spilling out of its cloth belly. A tear ran down my face and tumbled on to my stained hand-me-down tartan skirt. I murmured, ‘Oh Mum, what have you done to Bernadette’s arm, Mum? It’s like my doll, it’s just hanging there all loose …’

“My mother and I were quick to blame each other.

“‘YOU did this, Alannah.’

“You did this, Mum, I thought.”

Not long afterwards, the family of six – which included two elder brothers – left their rundown timber house in Scotts Rd, Geeveston, and abandoned their commercial apple orchard for the North-West Coast, where little brother Martin was born. For several years, the family ran a milk bar in Penguin.

“Our milk bar was known as ‘That Shocking Milk Bar’, run by ‘That Hill Family,” writes Hill. “We gained an appalling reputation within two weeks of taking over the milk bar on Ironcliffe Rd. Our pastries were never hot enough, our drinks never cold enough and our meat pies a constant disappointment … Half a mile away, our opposition milk bar was doing a roaring trade.”

Throughout her childhood and teens, when the family lived in Ulverstone, Hill says she struggled to make friends. Even her elder brothers were a mystery to her, moving “stealthily through our smoked-filled house, never speaking, never interacting with anyone, silent as ghosts and yet larger than life”.

Her world darkened when she was 12 , after she was allegedly sexually abused on a train by a relative on her way to visit her grandmother for a week’s holiday in Hobart.

“The guilt and shame that followed this event shattered my faith and trust in people,” she says. “Whatever was left of my childhood disappeared. It was almost the next day after what happened to me on the train that I began to reinvent myself. I couldn’t look back at that abused girl any longer.”

About three years ago, Hill came to Hobart to visit Mona with her musician partner Hugo Race, who was once a guitarist with Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds. They stayed in the same room at the guesthouse once known as Tantallon Boarding House she had moved to as a 16-year-old, the same age her son Edward, from a previous relationship, is now. “I did find it a bit haunting being back there,” she says, but she may stay again when she visits Hobart next week to promote the book.

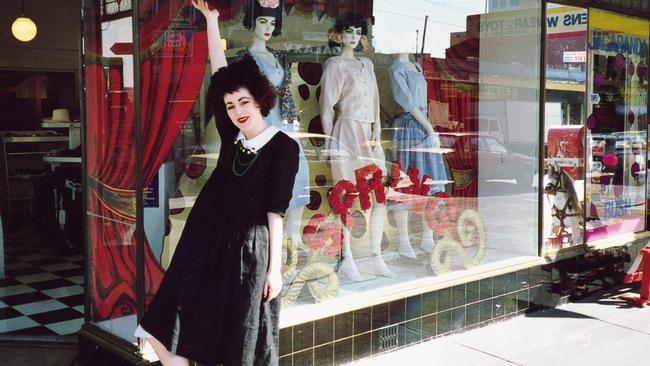

Hill arrived at the boarding house in 1977 carrying an old suitcase held shut with a black stocking. She had cut her hair into a black bob and smeared it with hot-pink cooking jelly on one side. She says she told her landlady “I am Alannah. Alannah Hill. I’ve come to Hobart to make my fortune!”

She was fired from her first job at a takeaway chain and struggled to hold down steady work. Her main outlet, apart from developing her eccentric wardrobe and dramatic make-up techniques, was to go out dancing at the ballroom of Hadley’s Orient Hotel, which held Extravaganza nights each Wednesday evening. By now living at another Battery Point rental, she was hanging out with two other unconventional girls. Decorated garbage bags were her wardrobe staple. She did not smoke and her drink of choice was red cordial.

For a while, it was fun. Then one night, she alleges, she was unknowingly given LSD by a policeman who was drinking with a colleague at the bar of the hotel, followed home by the men and raped. This time, she says she fought back, but to no avail.

“My head was a slaughterhouse of raging anger and sorrow,” she writes. “I remember wondering if I should kill myself as soon as the pain left my body or, alternatively, simply wash myself, fix my hair and dress up in my Sunday best and keep going. I didn’t leave the flat for two weeks.” She says she never reported the rape because she thought she would be blamed.

Within a year, she was on her way to Melbourne with all those suitcases of crazy clothes, including the sailor-girl outfit she wore on what was the first plane ride of her life, her habit of wearing a full face of make-up at all times, including to bed and swimming, already established. “I was lonely in Melbourne,” she says, “but I was not depressed. I was full of vim. I had a mantra in my head – ‘I’ll show you, I’ll show you all’.”

It took years, but show them she did. Her lucky break, seemingly the first of her life, came after about a year, when she spilt a coffee over the hands of a customer at the restaurant where she was waitressing. The customer was Jill Gould, who owned hippie boutique Indigo opposite Spaghetti Graffiti in Chapel St. Impressed by the punky young waitress’s bold personality and friendliness, she asked Hill if she had ever worked in retail. Hill replied “I’ve worked in retail my entire life! My entire life, Jill!”

It turned out Hill could sell the clothes off her very back. She stayed at the boutique for years and it was there that Jill and her business partner gave her the chance to design under her own name.

Later, she moved to a fashion company called Dialogue, producing her first full Alannah Hill collection, working 100-hour weeks in a cupboard-like space under the stairs. When Dialogue folded, she moved to Factory X, which opened the first Alannah Hill boutique, on Chapel, St, in 1997. Ever the longing daughter, she flew her parents over for the opening. “Now you listen to me, Lan, you LISTEN to me,” her mother warned her on the glittering night. “This does NOT feel RIGHT, I smell a rat and I just don’t like it! Now tell me again, why IS your name on all of the clothing? WHY?”

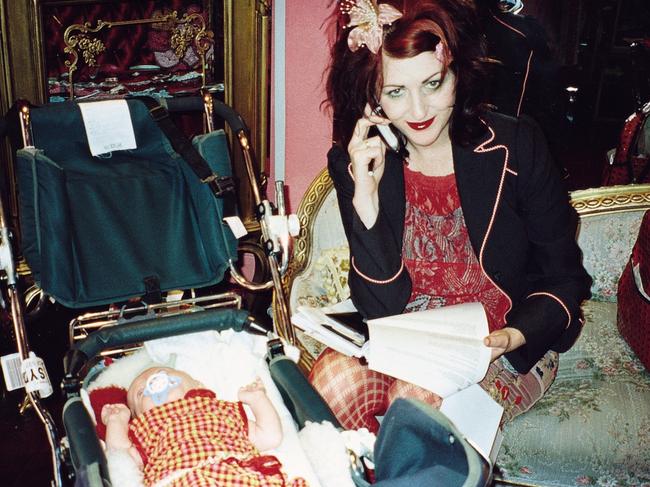

Alannah Hill had arrived. “Before I knew it, my fantastical girl dream became a business machine. It had everybody talking, including me,” she says. Over the next decade, she had a dream run with her label. She was her own best advertisement, with her elaborately feminine get-up and a phalanx of copycat shop girls delivering her coveted brand through her boudoir-style boutiques. Personally, there were highs, including the birth of son Edward in 2001, and lows, including her breakup with the newborn’s father a week after his birth. Business was buoyant for years and she made enough money to buy a $5 million home in Melbourne’s South Yarra in 2010.

But cracks were starting to appear. She was exhausted and feeling stretched in all directions. Then her mother died, her tricky, difficult, beloved mother, with whom she had only recently had a profound emotional breakthrough, and she was devastated. There was major conflict at work, too, with creative differences causing her to leave Factory X and the brand that bore her name. By August 2013, she was out and has had no further input into the brand. Everything belonged to Factory X. The posh home in South Yarra was sold and her Lady Muck dreams shattered.

“My identity was split between a brand I no longer had anything to do with and my personal sense of self,” she says. “‘Alannah Hill’ had been my greatest invention, my secret weapon against the forces of the world, and so without my name, I didn’t know how to go forward.”

She was 51, unemployed and scared, when she started the rebuilding process four years ago, launching the Louise Love label, this time as boss rather than employee. She sold the first range to David Jones and launched an online store. She says the clothes flew out the door. Then she had a change of heart. And stopped. She wanted to spend more time at home in her St Kilda apartment and to experience normal, everyday life as a mother including, to her son’s horror, volunteering at his school canteen.

The time had also come to tell her story. She knows the timing of publication is right, not just for her, but culturally. She only has to think of all the women coming up to her at readings to thank her and say #MeToo.

She is not sure what will come next. Perhaps the memoir will become a movie. She has been mulling over this possibility. Why not? There’s nothing to stop a “little mongrel bastard” from Tasmania from big-picture thinking.

Alannah Hill is already glorious proof of that.

If you or someone you know is in need of crisis or suicide-prevention support, please call Lifeline on 13 11 14 or visit lifeline.org. au/gethelp

Butterfly on a Pin, Hardie Grant, $33, is out now. Alannah Hill will be at Fullers Bookshop, 131 Collins St, Hobart, on Tuesday at 5.30pm. Tickets are free but booking is essential. Phone 6234 3800