TasWeekend: Claudio Alcorso was cut from a different cloth

Italian immigrant Claudio Alcorso is best known for establishing Moorilla Estate Winery. Now, a new biography allows us to appreciate the full scope of his influence on Tasmanian society.

Lifestyle

Don't miss out on the headlines from Lifestyle. Followed categories will be added to My News.

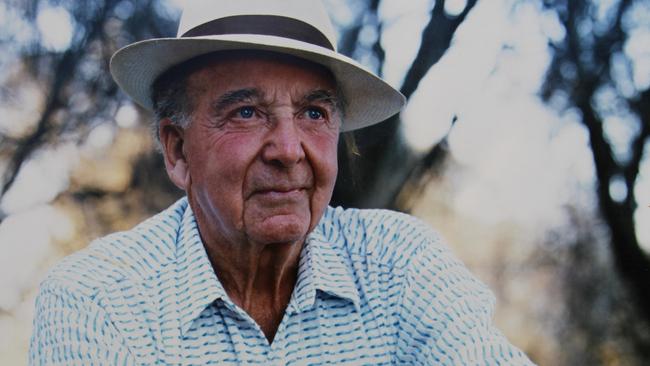

THE name Claudio Alcorso is one that a lot of Tasmanians will recognise, and while he is most often associated with the Moorilla Estate Winery, which he founded in the 1950s, there is still a long list of achievements on his resume that might surprise you. And while Alcorso’s biography is well recorded and certainly no great secret, what is surprising is how often he is overlooked as one of the state’s greatest movers and shakers. Hobart author and cultural historian Stephenie Cahalan first realised this strange collective oversight when her daughter was given a history assignment for school.

“She was given a history assignment about legacies and was given a list to pick from of Tasmanians who had made a lasting contribution to the state. And it was a pretty standard roll call all the usual names you’d expect to see on that kind of list.

“But I said no, let’s think of someone else who’s not on that list, and write about them instead. I had always had an interest in Claudio Alcorso and I noticed he wasn’t included, so I contacted his daughter and said my daughter wanted to research her father, and could she help us?

“She sent me a copy of his memoir, which was published in 1993, and when I read it I thought, ‘wow, this guy is amazing, why don’t we know more about him?’.”

Not only did Cahalan’s daughter get a highly commended mark for that assignment, it also planted the seed in Cahalan’s mind for a book about the man in question: Colour and Movement: The life of Claudio Alcorso.

Colour and Movement is not a biography, as his life story was already well recorded. Rather, she wanted to explore Alcorso’s legacy, his myriad contributions to Tasmania and the lasting impact his life has had on the state’s culture and lifestyle.

And that legacy is a sweeping one, spanning the wine industry, manufacturing, the arts and even fashion.

“One thing that a lot of people might not know is that Sheridan textiles was started by Claudio Alcorso,” Cahalan says. Yes, that’s right, Sheridan, as in towels and bedsheets. That was him. But more on that later.

Claudio Alcorso was born in Rome, Italy, in 1913, the son of a textile industrialist, and as a boy he started working in the family’s textile printing business.

But his family had a Jewish background and, just before the outbreak of World War II, as Italy started heading down a fascist path like Germany, Alcorso’s father realised it might be dangerous to remain in Rome.

“Claudio’s father knew Benito Mussolini,” Cahalan says, “and as things started looking bad, he asked him ‘do I need to get my family out of Rome?’ And Benito said, ‘yes, get your kids out.’.

“Claudio’s father was a very canny businessman, so he made sure the family didn’t leave penniless, they were very well appointed.

“So the first thing Claudio did was to go to London, where he studied economics and researched ways of starting up a business. Then he looked at Australia and realised nobody was printing colourful fabrics in-situ at the time.”

Alcorso migrated to Australia in 1938 and soon established a textile printing operation at Rushcutters Bay in Sydney, printing French and Italian designs onto fabric.

He found it disheartening that all the vibrant and athletic Australians he saw were wearing the sort of dull and dour colours common in English fashion, as was the trend at the time.

He wanted to see people wearing bright colours, floral designs, the same kind of beautiful textiles he knew from back home. But not long after starting his business, Italy formally entered the war, and Alcorso and his brother were detained as enemy aliens for four years in an internment camp as a result.

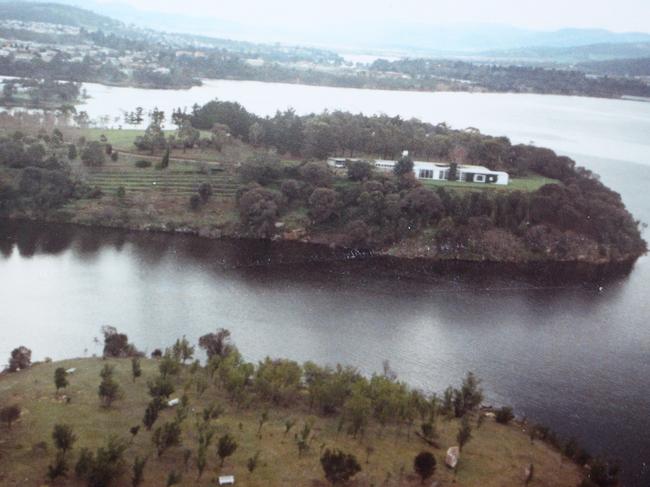

After being released, he relocated to Derwent Park in Tasmania, establishing a new textiles factory in Tasmania and putting down roots. In 1948, he purchased a 19ha plot of land on the banks of the Derwent, a site that would go on to become Moorilla Estate.

TASWEEKEND: TOP DROPS MAKE A SPLASH ON WORLD STAGE

In 1957, he commissioned renowned architect Sir Roy Grounds to build two homes on the property, one for his wife and children and one for his parents.

Both still stand. His family home is now the main entry for the Museum of Old and New Art (Mona) and his parents’ house, known as the Round House, is now Mona’s library. In 1958, he planted the first riesling grapes on his property, which marked the beginning of a winemaking legacy which continues to this day.

When the winery went into receivership in the 1990s, Mona founder David Walsh bought the property, but Alcorso and his wife Lesley continued to live on-site in the Round House.

Alcorso died in 2000, Mona opened to enormous fanfare in 2011, and the rest is, well, history.

But there was so much more to Alcorso’s life, and much of it is not widely known. His textile business eventually became Sheridan in 1967, and is now literally a household name, present in countless households in the form of bed linen, towels, children’s clothing and more.

“In doing my research for this book, I was most surprised by the breadth of his influence,” Cahalan says. “He was a true industrialist with textiles, and bold and ambitious in terms of wine. He was bold in pursuing ideas and progressing his vision and completely unapologetic about trying to achieve the outcomes he was chasing.

“People told him he could never grow grapes for wine in Tasmania but he said, ‘well, I’m from Italy, and there are plenty of cool climate wines there!’ And he just did it.

“Also, he wasn’t doing things on his own, he was a ferocious networker. That’s how he got things done. He wasn’t afraid to make calls and ask for favours, which is not the English way of doing things, and Australia was very English, in terms of the way people did things at the time.”

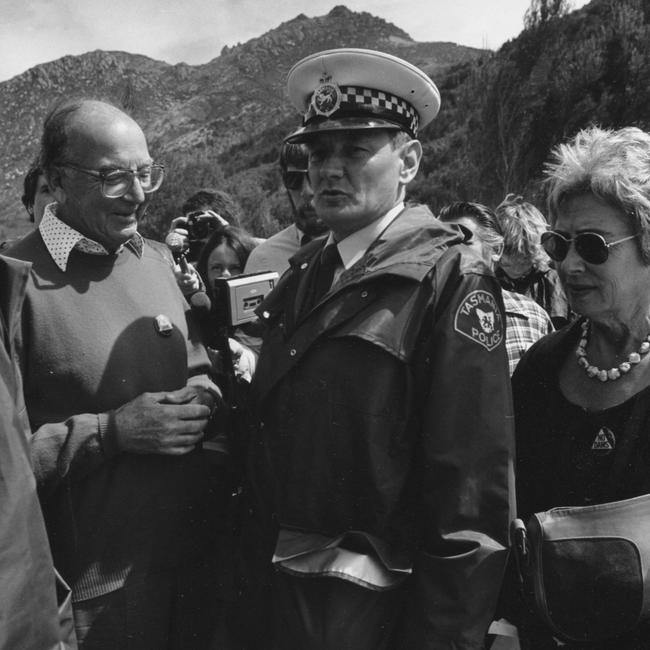

He and Lesley were also passionate about the environment, both being arrested for being part of the blockade during the Franklin River campaign in 1982.

“Protesters came in from all over the place to be part of that action and the Alcorsos even billeted some of them at Moorilla,” Cahalan says.

“Can you imagine how wonderful that would have been, the beautiful location, the artwork, the wine, the Alcorsos’ company. The people billeted there were pretty lucky, I think!”

But even more than his contributions to the wine industry and his endless celebration of art and culture through his patronage of the arts,

Cahalan believes Alcorso’s biggest impact might be the way he helped build Tasmania’s very sense of identity. She says he envisioned an everyday life for Tasmanians — and Australians — in which they would be constantly influenced by beauty, art, culture and humanism.

He was even instrumental in lobbying the State Government to preserve Salamanca Place as an arts and cultural precinct for the city.

“He grew up in Rome, in an everyday environment that was groaning under the weight of its history, evidence of it everywhere,” she says. “Meanwhile, in Australia in the 1950s and 1960s, we were only just starting to recognise our first people and owning up to the countless years of human history that existed here before Europeans arrived, which we had annihilated or ignored.

“He was able to see that, and he tried to bring Aboriginal culture into the light. He was also an outsider, an Italian, a “wog” to a lot of people.

“The people who knew him loved him, but he also got a certain amount of “you’re not from here”, so he was a very interesting and complicated person, very thoughtful, and always trying to help the emerging identity of Australia find and identify itself.”

Alcorso’s Moorilla property is now home to the famed Museum of Old and New Art and, despite the monolithic building that now envelops the site, Cahalan believes Alcorso would be very happy with what Moorilla has become and what it has come to represent.

“Mona is continuing that theme of celebrating art, culture and human creativity. Claudio Alcorso and [Mona founder] David Walsh are both these unapologetic champions of art and creativity who aren’t bogged down by people’s opinions — they just do what they do because they can.

“A lot of people have that capacity to do what they did but don’t do it. If more people were a bit braver, that would be great. Alcorso showed that everybody can be a patron and help in their own capacity, in some way, by supporting somebody who’s getting a venture going. There are so many others that aren’t celebrated, who are making profound positive impacts and deserve to be noted.

“So maybe look a little bit further afield, or even right next door, and see what that person is doing to create a positive impact into the future.

“They don’t need their names up in lights, but you can give them a nod and say ‘nice work!’.”

Perhaps most poignantly, Cahalan believes there is an important message to be found in the way Alcorso was treated during his earliest days in Australia.

Despite being treated as an enemy of the state and locked in an internment camp during World War II, he bore no grudge and still went on to make enormous contributions to his adopted home.

“There might be other Claudios locked inside Australian detention centres and child detention centres right at this very moment, or living in the back blocks of the northern suburbs of Hobart that he loved so much. He deliberately stayed out there when others of his status were moving to places like Sandy Bay. He loved the community where he lived.

“He showed that there is no pathway to success or cookie-cutter for excellence. Those aren’t things you can contrive, you need to have that drive and that spirit.”

Colour and Movement: The Life of Claudio Alcorso, by Stephenie Cahalan, is on sale now for $49.95