TasWeekend: Businesswoman Jan Cameron plays the long game

SHE’S the animal-loving “deal junkie” who wants to halt the sale of Australia’s largest dairy enterprise to a Chinese bidder. But not everyone wants Jan Cameron to succeed, writes SALLY GLAETZER.

Lifestyle

Don't miss out on the headlines from Lifestyle. Followed categories will be added to My News.

I HALF expect Jan Cameron not to turn up to our planned interview at Hobart’s Blue Eye restaurant, given her tendency not to return calls or respond to messages. But there she is, a glass of wine in hand and an enormous, lethargic boxer-cross sprawled on a dog bed beside the table. Tszyu (named after Australian boxer Kostya Tszyu) and her owner are welcome regulars, judging by the friendly familiarity of the waitress at the waterside seafood restaurant near Cameron’s apartment.

I shake off my preconception, based on Cameron’s reputation for reclusiveness, of someone prickly and unapproachable as she greets me jovially and pours me a glass of the Native Point pinot gris she is drinking.

“I find wine sort of lubricates my brain,” she says, which is music to the ears of a journalist hoping to get an insight into the mind of one of Tasmania’s most polarising business figures.

To further break the ice, I ask Cameron how she came to be Tszyu’s “human companion”, as she calls herself. She was changing a flat tyre on the Tasman Highway near the Lake Leake turn-off when Tszyu, a scrawny neglected pup, wandered out of the bush.

“She’s coming on 14 and she’s a grumpy old bag like I am,” Cameron says.

At the time of our interview, the Kathmandu adventure-wear founder is in the midst of a bid for Australia’s largest dairy enterprise, Tasmania’s Van Diemen’s Land Company. The farm sale has been bogged down in legal wrangling for months and has just turned political. A number of independent federal MPs have jumped on board, arguing the company should be sold to locals, rather than the leading Chinese bidder, despite it having always been foreign-owned.

Given Cameron’s reputation for buying up and mothballing properties elsewhere in the state, locals in the North-West are alarmed by her interest in the prized dairy company, which includes 25 farms, a stud and 13 dairies. They have heard how she bought the Silver Sands Resort at Bicheno 14 years ago and let it and other properties languish. There is also some resentment about Cameron’s purchase, along with fellow entrepreneur Graeme Wood, of Gunns’ old Triabunna woodchip mill.

Cameron, 63, is unfazed by the way she is perceived and has little desire to defend herself, although she does object to suggestions she “shut down” the Triabunna mill.

“Something that is really misconstrued is that I shut down the Triabunna woodchip operation. It is just not true,” she says. “Gunns closed that down. Gunns failed. Why? Because they were trying to sell a commodity product into the world market with dropping prices.”

Cameron and Wood bought the mill for $10 million in 2011, after Gunns had ceased operations at the site because of a collapsing woodchip market. Gunns’ decision to sell to a pair of environmentally minded multimillionaires was ill-received by many because it dashed hopes the region’s woodchipping industry would be revived.

Wood and Cameron are both nouveau Tasmanians, having fallen in love with the state after making their millions elsewhere. Wood’s initial fortune was made with travel booking website wotif.com.

A keen sailor, he divides his time between Sydney and Battery Point.

Cameron, who grew up in Melbourne, splits her time between Bicheno and Hobart, with regular trips interstate and overseas. Their business partnership, set up purely to buy the Triabunna mill, ended in late 2014 after a brief legal dispute, which resulted in Wood buying out Cameron’s stake.

Cameron says she was uncomfortable with Wood’s grand plans for gardens, a conference centre, education institute and accommodation at Triabunna. She would rather have “sat on” the site, as she has so controversially done with her assets further up the coast.

“I probably would have had the same approach as I’ve had in Bicheno, which would have frustrated local people,” she says. “But waiting five or 10 years is insignificant in terms of creating something special and long-lasting.

“My approach is to sit on something, wait for the right timing and then, when you feel the planets align, you do something.”

Cameron says the planets have finally aligned for action on the dilapidated Silver Sands at Bicheno, which occupies a prime waterfront site but has been closed since last year. She has engaged Hobart architects Poppy Taylor and Mat Hinds to design the refurbishment in collaboration with a European architect, whom she refuses to name.

“I have been a little bit distracted in the past 14 years since I bought that site. But it’s in the past couple of years I’ve actually come up with a vision for that redevelopment. We hope to start building in … aaaah … 12 months,” she says, her vagueness sure to do little to placate her critics in the coastal tourist village.

I ask Cameron if she hopes locals will forgive her tardiness in developing the Silver Sands once construction work starts. After a lengthy pause, she replies: “I’m not looking for forgiveness.”

Later I leave a message on Wood’s mobile, seeking his response to some of Cameron’s comments about Triabunna. When he phones back he is fired up, not so much by what Cameron has said but by what he calls the political interference with his Triabunna plans.

“Jan and I get on just fine,” he says. “We had a bit of a falling out but we get on. We’re both realistic, we both have a history of making commercial ventures work. The Government of Tasmania has a history of f---ing things up.”

His fury is over the parliamentary inquiry into the sale of the Triabunna mill, which was the State Government’s indignant response to the once-key forestry asset falling into the hands of environmentalists. After summoning witnesses, including Wood, the inquiry committee concluded the Government should get on and support his plans.

“I do not engage in political discussion in Tasmania anymore,” he says, revealing the time-consuming inquiry was enough to make him consider walking away from the state. “I believe in the long term and I ignore politics in Tasmania because it’s so inane and stupid and inbred. Politicians come and go ... I’ve got such little regard for them I can’t be bothered talking to them.”

His distaste for politicians aside, Wood says he is committed to the Spring Bay Mill development, although he is downsizing from the original ambitious plans. Ironically, given his disagreement with Cameron on the need to press on with the development, he admits construction work is still a long way off, perhaps even years.

“I’m revisiting it in the hope we can find a scaled-down version we can start work on,” Wood says. “It’s become more realistic. It’s a beautiful place so I just want to make it work, even if I have to wait a year or two or five.”

When Cameron left home in the early ’70s, her mother told her: “Don’t ever take up smoking and don’t get married.”

“Funny, ay?” Cameron says, her decades in New Zealand bubbling to the surface.

The non-smoker would have abided by both pieces of advice had her Swiss boyfriend several years later not needed a visa.

Cameron’s parents, who have passed away, were both born in 1913. Her mother was a teacher and her father a businessman. Both were deeply affected by the Depression.

“My parents were really very frugal,” Cameron says. “They were Presbyterian teetotallers. The Depression very much impacted on their lives. My brother and sister got married when I was quite young so I got to sit around listening to them.”

Her parents’ marriage was unhappy. Although they conformed to what Cameron calls the “father knows best convention” during her childhood, there was an underlying antagonism. “In terms of my father, my mother was very passive-aggressive,” Cameron says. “He was just straight-out aggressive. They became separated in their 60s. It was a very dysfunctional family. It left me with no desire to have children or get married.”

It was her mother in particular who impressed on Cameron the importance of financial security. “And even more so the importance of a woman to control her own financial destiny,” Cameron says.

It seems apt her private investment company, The Elsie Cameron Foundation, which donates many tens of millions of dollars to conservation and animal welfare projects, bears her mother’s name.

It was a very dysfunctional family. It left me with no desire to have children or get married.

As a teenager in the ’60s, Cameron itched for a freer way of life than her parents’. “In that era there was a big cultural gap between parents and kids, and we all just wanted to leave home,” Cameron says. “We wanted freedom to do all sorts of things our parents disapproved of. Not that I was a party person – I wasn’t, not at all – it was more about freedom of thought and movement.”

After two years of studying medicine in Melbourne, she left for New Zealand in 1972, pursuing her passion for bushwalking and rock-climbing. In 1980, she married fellow rock-climber Bernard Wicht, who had come out from Switzerland with very little English.

“I’ve got to ‘fess up and say yes, we were happy living together and having a relationship. But had it not been for the inconvenience of residency, we wouldn’t have got married,” she says.

Cameron famously started sewing sleeping bags for herself and friends while living in Melbourne, before setting up shop in New Zealand and eventually expanding what became the Kathmandu empire into Australia. Her early business partners were Wicht and New Zealander John Pawson, who years later died in a rock-climbing accident. When a private equity consortium bought Kathmandu in 2006, Cameron netted a reported $247 million.

She and Wicht split in 1987 but remain business colleagues and close friends. In fact, Cameron is preparing to fly to Italy to meet him and his family for a European food and wine vacation. “He’s doing a little cultural tour with his wife and kids in Italy for a week and I’ve demanded to join them,” Cameron laughs. “I seem to collect exes … some people might call me a hoarder.”

I ask if she has succeeded in achieving the freedom she desired as a young adult. “Absolutely,” she says. “Personally, I have freedom because I don’t have a partner. That means a lot. And I’m not aligned to any political group. I don’t have any responsibilities to other people, I don’t have kids, I don’t have to hold down a job.”

While she is investing considerable time and funds in her attempt to snatch VDL from the hands of a Chinese investor, Cameron says she is not losing any sleep over it.

“I’m passionate about it but it’s not my decision,” she says. “It’s the Australian public’s decision, really, whether they’re going to support Australian ownership of critical agricultural land.”

In the windswept North-West corner of Tasmania is Woolnorth Station, the jewel in the VDL crown, where wind turbines dot the coastline and the dairy cows breathe in the cleanest air on Earth. The 17,000ha property is a refuge for threatened species including one of the largest remaining populations of disease-free Tasmanian devils.

The site’s history is rich and bloodstained. The VDL company was formed in London in 1825 and Woolnorth was part of the land it was granted by King George IV for wool production. In 1828, white settlers massacred 30 Aborigines on the property, throwing some of their bodies from a cliff into the sea.

VDL remained in British hands until 1993 when it was bought by a New Zealand company. It was taken over by the New Plymouth District Council of New Zealand in 2007. The 100 million litres of milk produced each year is supplied to Fonterra, the world’s largest dairy exporter, making products such as Bega and Mainland cheese, Western Star butter and Nestle yoghurt.

Chinese billionaire Lu Xianfeng, whose successful $280 million bid for VDL is subject only to Foreign Investment Review Board approval, plans to maintain the existing arrangement with Fonterra but boost production with nine new dairy farms.

Australian company TasFoods Ltd, headed by Tasmanian Rob Woolley, was previously announced as the successful bidder for VDL with a $250 million offer. Cameron, an investment colleague of Woolley, was to put in $50 million as part of the deal. When New Plymouth Council instead accepted Lu’s bid, TasFoods took the council to court, eventually accepting a $1.25 million compensation settlement.

While her colleagues at TasFoods were caught up in the court proceedings Cameron launched a third, last-ditch attempt to bring VDL into Australian hands. Since last month, she has been trying to lobby the Federal Government to block the sale to Lu, although Treasurer Scott Morrison will not meet her. Cameron is rallying Australian investors to put together an offer similar to Lu’s, which she would underwrite. She has also launched a website called Save the Farm, promoting the idea Australia’s prime agricultural land should not be sold off to foreigners.

The fight to bring VDL under Australian ownership has been taken up by the likes of businessman Dick Smith, Tasmanian MP Andrew Wilkie and South Australian senator Nick Xenophon. It is reminiscent of the tussle to stop the sale of the Kidman cattle properties to foreigners, with one glaring difference: unlike S. Kidman & Co, VDL has never been owned by Australians.

Billionaire trucking magnate Lindsay Fox is making a similarly belated bid to keep Kidman & Co in Australian hands, making a counter offer to rival a $300 million Chinese bid.

Dick Smith fronts a TV advertisement promoting the Save the Farm campaign, although he reveals to TasWeekend he has only met Cameron once and has declined to personally invest with her in VDL because he already has a stake in an agricultural company.

“I think Jan Cameron is very capable,” Smith says. “She says she can get the money and she should be given the chance. If you sell it off overseas, all the profits will end up in overseas hands.”

In Cameron’s sky-high apartment, she shows me a set of speculative branding images for high-end dairy products bearing a proposed Van Diemen’s Land Company label. The marketing is impressive, with simple, sophisticated packaging for products such as brie, double cream and glass-bottled milk. Cameron believes there is more money to be made by focusing on VDL’s 190-year history and pristine location than supplying the milk anonymously to a multinational such as Fonterra.

“Tasmanians really need to understand the power of branding. I can only use Bellamy’s as a prime example of that,” Cameron says.

Last year, Tasmanian baby food manufacturer Bellamy’s became a billion-dollar company on the back of soaring demand from Asia. Cameron invested $5 million in the company and walked away with $36 million when it listed on the ASX in the middle of 2014.

“Bellamy’s is now worth $1.3 billion,” Cameron says. “I’m not saying VDL can rise to such stratospheric heights but Tasmanians have to look at something like that. They’ve got to look at the strengths of what a brand can do.”

Last May, the Australian Financial Review speculated Cameron reinvested in Bellamy’s via Singapore-based entity The Black Prince Foundation, which is now the company’s biggest shareholder with about 15 per cent. Cameron tells TasWeekend The Black Prince is not hers, but says the Elsie Cameron Foundation owns a small stake in Bellamy’s.

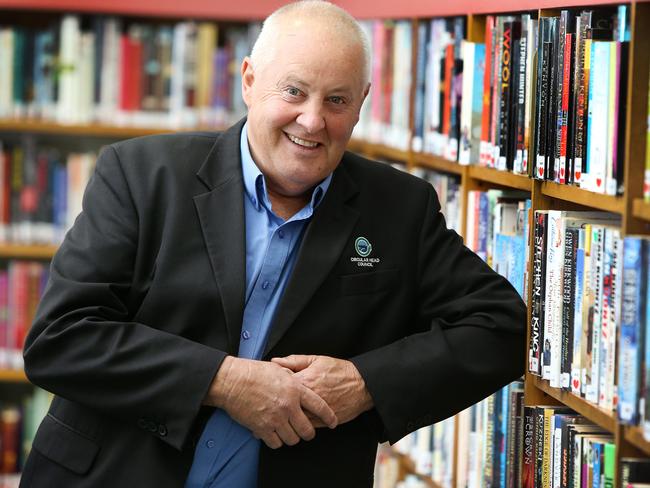

Up in Circular Head, local mayor Daryl Quilliam knows the VDL farms like the back of his hand, having supplied them with agricultural products for the past 15 years. He is miffed politicians such as Wilkie and Xenophon have jumped on the Save the Farm bandwagon without even bothering to talk to him.

“I know the company extremely well and I know the importance of it for the local community, and these politicians haven’t spoken to me at all about it. Jan Cameron hasn’t talked to me, either. Mr Lu has,” Quilliam says.

Quilliam is impressed by Lu’s promise to maintain the status quo at VDL but increase job opportunities by expanding production. He is sceptical of Cameron’s ability and desire to invest in the company in the same way, given her dealings in Triabunna and Bicheno. He says locals are also disturbed by Cameron’s desire to hand back part of the Woolnorth property to Aborigines and conserve vegetation earmarked for clearance. The worry is she is more concerned about Tasmanian devils and Aboriginal reconciliation than job creation.

“We would rather it be in Tasmanian ownership if they had the ability to spend the money on it that Mr Lu is prepared to spend on it,” Quilliam says. “We’re sceptical about her involvement and her ability to be able to spend the money that’s necessary to give a lot more work to people in our area.”

Quilliam’s concerns about Cameron’s finances spring from her business failure in 2012 with discount chain store company Retail Adventures. The collapse of the company, which resulted in the closure of Tasmania’s Chickenfeed stores, is believed to have cost Cameron most of her Kathmandu fortune. The retail “misadventure”, as she has dubbed it, stripped Cameron of the title of Australia’s fourth-richest woman. Cameron says she is capable of underwriting a $280 million bid for VDL but refuses to put a figure on her worth. However, media reports say she recently earned a tidy sum by selling her stake in outdoor gear retailer Macpac.

I may sound like a raving ratbag greenie but I’m actually not, I’m a very hard-headed commercial person.

“I may sound like a raving ratbag greenie but I’m actually not, I’m a very hard-headed commercial person,” Cameron says. “If you follow my business career it’s been all about making money. I’ve had successes with Kathmandu, Macpac, Bellamy’s. They have earned me an incredible amount of money. I have had a very, very significant failure in Retail Adventures and I attribute that to a number of things: poor decision-making on my part and really losing sight of, in retail, that brand is everything.

“Every failure is a huge learning experience, provided you’re willing to critically examine your responsibility in that failure.”

It is hard to think of a person, outside politics, who polarises the Tasmanian community in the same way as Cameron. She is a woman of infinite contradictions. On one hand, she is accused of holding back Bicheno’s tourism potential by failing to develop many of the properties she owns there. On the other, she helps fund local health and childcare centres, animal hospitals and conservation projects.

She wants to save the environment, but invests in discount retail chains peddling mass-produced – and mostly plastic – products from Asia. In another twist, she donated the profits from Tasmania’s Chickenfeed stores, close to $10 million a year, to charity.

In 2010, when Chickenfeed was still operating, she announced she was closing the company’s service centre at Cambridge and sacking 60 workers. It was an unpopular move, but the same day she handed over the warehouse for the establishment of Foodbank, a charity that distributes donated supermarket food to welfare groups.

Former Tasmanian Woolworths boss Michael Kent was the founding chairman of Foodbank. Now he is the mayor of the Glamorgan Spring Bay municipality, which takes in Triabunna and Bicheno.

“I would see myself as a business colleague and friend of Jan Cameron but I don’t necessarily agree with everything she does,” Kent says. “When I was chairman of the RSPCA, I reckon conservatively she gave $3.5 million or thereabouts. That was more or less to build a veterinary surgery for desexing and all that sort of business. She helped me immensely when I introduced Foodbank to Tasmania and she expected nothing in return.”

Although he appreciates her willingness to dig deep for the causes she champions, Kent shakes his head at some of Cameron’s business and real estate dealings. But he is confident there is method to her madness.

“On one hand, there are people in Bicheno concerned some of the things she’s bought she’s just let other people run or lets them run down. On the other hand, I know Silver Sands is going to be pulled down to become European-designed units,” Kent says. “That will cost her about $10 million. Whatever she hasn’t done in Bicheno will be turned around in five minutes once she does that.”

After the demise of Retail Adventures, Cameron says she is done with discount retailing in Australia. But not, it seems, overseas. “I’m looking at an investment,” she says cagily, refusing to give details. “There are always opportunities.”

In her words, Cameron is a “deal junkie”. If she manages to snare VDL, or otherwise establish her high-end dairy brand, the profits will be pumped back into her private foundation for philanthropy and further investments.

After our interview, as the VDL foreign ownership debate heats up, I call Cameron for an update. Eventually she calls back, sleep-groggy, from London. While she remains as committed to the VDL bid as ever, Cameron says she has received no update or word of encouragement from the Federal Government.

True to form it is clear Cameron is not wasting any time waiting around for the FIRB or Scott Morrison to make a decision on the Chinese bid for the dairy company. As well as wining and dining her way through Italy with her ex-husband and his family, she has been using her trip to Europe to investigate yet another business deal.

The Foreign Investment Review Board decision on the sale of the Van Diemen’s Land Dairy Company to a Chinese buyer is expected by the end of the month

For more great lifestyle reads, pick up a copy of TasWeekend in your Saturday Mercury.