Elaine Reeves gets to grips with the ‘newest’ taste sensation, umami

It’s all about taste. Nothing is nutritious unless you put it in your mouth and swallow it, writes ELAINE REEVES in an exploration of umami.

Taste Tasmania

Don't miss out on the headlines from Taste Tasmania. Followed categories will be added to My News.

A SYMPOSIUM on colloids and interfaces is an unlikely place to find me, but at the end of a day of talks that included “universal nano-lithographic technique for different shaped functional anisotropic nanoparticles” Ole Mouritsen stepped up to speak on the science of taste, and there I was for the plenary session at the Hotel Grand Chancellor.

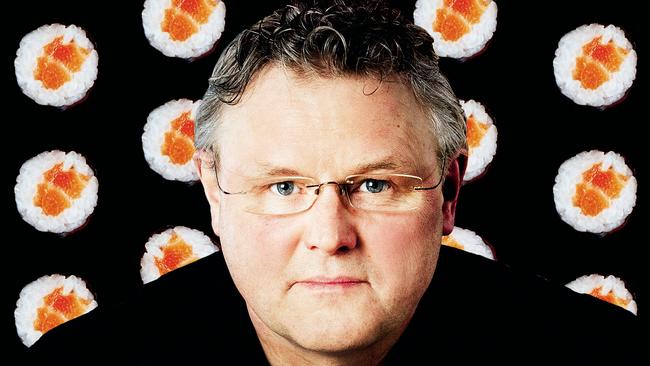

The professor of gastrophysics at the University of Copenhagen says this new science is to gastronomy what biophysics is to biology.

Whatever the science of nutrition may have to tell us, taste comes first. After all, nothing is nutritious unless you put it in your mouth and swallow it.

Much of Ole’s talk addressed the “newest” taste, umami. Sour, salty, sweet and bitter were well-established when in 1908 Japanese chemist Kikunae Ikeda called for recognition of a fifth primary taste that “was quite distinct from the other tastes and could not be produced by any combination of other qualities”.

He combined the Japanese word for deliciousness, umai, with that for taste, mi, and called it “umami”.

The chemical basis of umami is glutamic acid. A few years later, one Akira Kuninaka worked out that combining the glutamate-rich foods with others containing chemicals called nucleotides greatly enhanced the umami taste. He called this second stream of foods synergistic umami.

What might be regarded as the oomph of a taste has little bearing on the level of umami. In the basal stream, asparagus has more than caviar but green peas beat them both.

Worcestershire sauce is a low six, soy sauce is number 19. Fourth from top in the basal stream is parmesan cheese, then fish sauce, Vegemite and top, dried seaweed (konbu).

Fourth from top in the synergistic stream is chicken, then mackerel, anchovy paste and at the top, katsuobushi, or bonito flakes.

Ikeda was eating dashi soup, which includes both konbu and bonito flakes, when he was inspired to investigate such deliciousness.

Few foods are in both streams. Exceptions include asparagus and tomatoes. Some of our favourite pairings represent basal (first mentioned) and synergistic (second mentioned) umami — egg and bacon, cheese and ham, tomatoes and beef and tomato sauce and a burger.

Although umami won’t appear on any label nutrition list, its presence can be very important in making food attractive.

A little taste of konbu that had been soaked in soy sauce proved that umami gets the saliva going. The presence of umami increases the appetite, which can be very important for the elderly or those on chemo treatment.

Ole said desserts that have umami can be 30 per cent lower in sugar and still be satisfying.

Umami comes to fore when we simmer, fry, grill, dry, ripen, age, preserve, and especially, ferment food. Katsuobushi (bonito flakes) come from tuna that has been dried, fermented and smoked — no wonder it is the essence of umami.

Or you might want to simply sprinkle in some MSG … I remember when Tasmanian truffle agriculture was in its infancy, a grower begged me not to mention the identical glutamic acid component in truffles and in monosodium glutamate (MSG), lest his luxury product be tainted by the association.

Both truffles and MSG famously enhance the flavour of what they are cooked with.

Kikunae Ikeda, the man who coined the name umami, founded an MSG company that continues to manufacture “delicious flavour” to this day.

In answer to a question after his talk, Ole Mouritsen said he was a chemist by training and he could not “tell the difference if a glutamate ion comes from a chemical factory or the inside of a tomato”.

He said the prejudice against MSG arose in 1968 when a US doctor coined term “Chinese restaurant syndrome” for claimed bad reactions to MSG.

Today, MSG is “the most well studied food compound of all” and studies of people who claim to have an allergic reaction to it showed only 1 or 2 per cent actually did — the same proportion of people who have adverse reactions to any food compound.

“A scientist has no way of understanding why one should be scared of MSG,” he said. Except perhaps: “You could have concerns that the food industry is using MSG to disguise poor raw ingredients, but that is a different matter, nothing to do with the chemistry.”

elaine.reeves@antmail.com.au