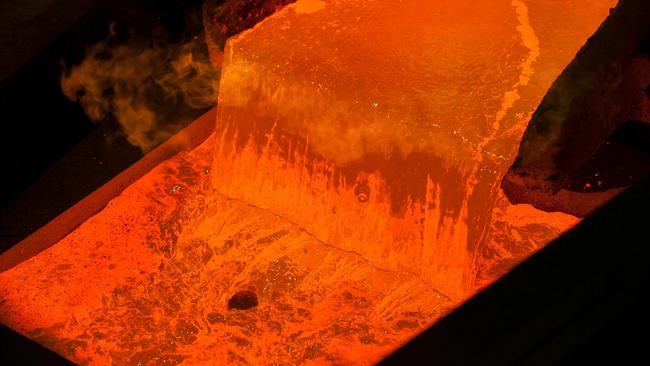

Australian miners nervous as copper ore profits collapse

Australian miners are watching nervously as China’s next move determines their future – and Australia’s.

Mining

Don't miss out on the headlines from Mining. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Australian miners are watching nervously as China’s biggest copper smelters meet in Beijing this week to discuss a response to collapsing profits.

Copper ore processing fees – essentially the value added for smelting ore into pure copper – have fallen to their lowest level since the Great Financial Crisis of 2013.

That’s not due to an oversupply of copper ore. In fact, several unexpected mine closures have occurred around the world.

It’s because of a dramatic expansion of China’s capacity to smelt it.

And a global fall in demand as the clean energy transition stalls.

Now they’re having to cut their fees to compete with India and Indonesia, which have also increased their copper smelting capacity.

With most of China’s copper industry now state-owned, representatives of the 15 major smelters have been called to Beijing this week to discuss a co-ordinated response – including potential production cuts.

While the future of copper as a critical component of new industries such as electric vehicles, wind turbines, and electrified industries is not in doubt, economic analysts say global supply chains are.

China’s state-owned critical minerals corporations are not beholden to shareholder interests or balance sheets.

And once internationally regulated corporations retreat from a financially unviable sector, close mines, and liquidate processing infrastructure, China’s state-owned operations can step back in and capture a much greater portion of the global market.

Price shock

Global demand for copper has choked as consumers cut back their spending in the face of soaring living costs. But increased energy (mostly gas) costs — a central part of any smelting process — are also unsettling the equation.

As a result, an expected surge in global electric vehicle sales is yet to arise.

And an anticipated electrification of the global economy has slowed.

China’s economy is in a particularly dark place. And it’s responsible for more than half the world’s copper consumption.

The copper slump first emerged in January with a sharp downturn in manufacturing orders. That’s now flowing through to all sectors of the supply chain.

China’s copper smelters last week reported a 90 per cent fall in spot market prices over the past six months.

Bloomberg reports this has resulted in BHP recently selling them copper concentrate from its Chilean Escondida mine at $US12 metric tonne “and at $US3 and 0.3 cents to at least one trader, according to people familiar with the deals”.

Meanwhile, Beijing continues to invest heavily in securing metal and mineral supplies from more “friendly” nations than Australia.

It is investing $A1.5 billion in upgrading an old railway network linking Zambia’s copper belt and the Democratic Republic of Congo with the Tanzanian Indian Ocean port of Dar es Salaam.

It’s part of Chairman Xi Jinping’s “Belt and Road” strategy to secure supplies of critical resources in the face of increased global disruption.

According to the state-controlled South China Morning Post, the upgraded rail line “will compete directly with a (new) railroad backed by the US and EU” seeking to link Zambia’s copper and DRC minerals to Angola’s Lobito port on the Atlantic.

“Most of these minerals are now exported to China for processing,” the SCMP states.

Critical copper

“Digging it and shipping it” represents two-thirds of Australian export income. In the last financial year, that was a record $A455 billion — up 10 per cent from the previous record set a year earlier.

Coal was worth $128 billion. Iron ore was $125 billion. And copper was in fifth place at $12.5 billion.

But a Department of Industry, Science and Resources report published in April last year says coal has peaked, with foreign markets already on a path to slash consumption by about one third over the next four to five years. By 2028, Australian coal revenue is forecast to be about $19 billion.

The Federal Government has placed its hopes on soaring demand for critical minerals.

Geoscience Australia defines a critical mineral as essential for the function of modern technologies, economies, or national security. However, it must also be at risk of supply chain disruption or manipulation.

Lithium, nickel, cobalt, and rare earth metals exports are expected to grow significantly, but volumes are likely to remain comparatively low.

Meanwhile, market analysts are highly optimistic about the future of bulk copper, with some projecting annual earnings growth of 70 per cent over the next five years. And that’s needed to help make up the national accounts shortfall generated by the collapse of coal.

Australia has the world’s second-largest copper reserves, representing 10 per cent of known deposits. However, it is listed as only the world’s eighth largest producer, digging up 810,000 metric tonnes last year.

Canberra has not designated copper as a critical mineral. The US, EU and China have.

Industry analysts – keenly aware of the government subsidies such a designation entails – argue this doesn’t reflect the red metal’s global significance.

Jamie Seidel is a freelance writer | @JamieSeidel

Originally published as Australian miners nervous as copper ore profits collapse