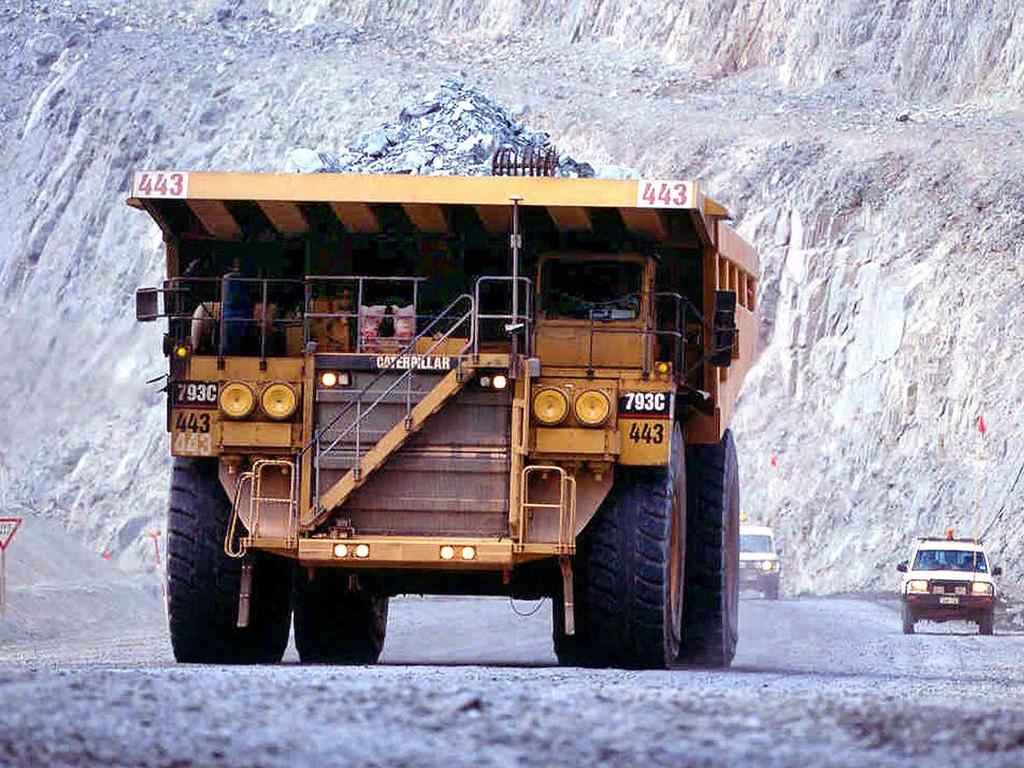

Australia on the brink as iron ore, nickel, lithium prices collapse

The collapse of three of Australia’s biggest money spinners leaves the country very vulnerable to China’s every move.

Australia prides itself in being the world’s quarry. But China is its biggest buyer. Now the collapse of the nickel industry reveals a supermarket-style price manipulation scandal is being played out on a grand scale.

Competition is great. Until you get a winner. And that winner’s been taking performance enhancers …

Canberra is having to fork out billions of dollars in emergency corporate aid and surrender royalty income after a slump in global nickel prices. They have fallen more than two-thirds – from a high of $US50,000 per metric ton in 2022 to about $US16,500 this week.

Thousands of jobs are on the line as big multinational mining companies urgently review the viability of their operations across Australia.

But the nickel industry isn’t the only mineral facing massive market disruption.

Steel and iron ore prices have collapsed. As has lithium.

The cause is the same across the board: China’s dumping huge quantities on already depressed markets.

And that makes it unviable for competitors to continue competing.

“Far from a hypothetical, Beijing has already used its near-monopolistic global supply-chain control of (rare earth elements) to strategic advantage against the US and Japan,” warns the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI).

“We should expect it to do so again.”

Market force

Nickel is not just any mineral.

It’s critical for producing high-capacity batteries, stainless steel and many other advanced alloys.

It’s one of a host of difficult-to-mine and expensive-to-refine materials (generally classified as rare earth elements and critical minerals) that play central roles in modern electronics and high-performance technology.

These are central to the global race to combat climate change – and rebuild militaries in the face of the territorial ambitions of Russia and China.

But Beijing’s willingness to subsidise every step of production and bear the environmental fallout of chemical and energy-intensive processes means it’s now the source of about 80 per cent of the rare earths processed worldwide. That includes 90 per cent of lithium, 70 per cent of gallium, and 70 per cent of germanium.

China refines about 35 per cent of all nickel output.

And last year, it took control of a further 15 per cent once new Chinese-owned-and-operated plants in Indonesia came online.

“Its incredibly low cost of processing and competitive labour market gives it an almost unassailable advantage, turning suppliers into price takers rather than price makers,” says Monash University critical minerals analyst Associate Professor Mohan Yellishetty.

‘Dig it and ship it’

Australia is notorious for selling off the farm and failing to value-add its food and mineral produce.

China, however, has for decades had a single-minded focus on building market dominance.

It’s invested heavily in building advanced industries, such as silicon chip and clean energy technologies.

As a result, it’s now the world leader in the entire lithium extraction, refining and production chain – among others.

“It has paid substantial environmental costs through trial-and-error innovation and has now developed dominant advantages in not just the scale of mass production, but also green technologies used in lithium processing,” Dr Marina Yue Zhang of the Australia-China Relations Institute argues in the Lowy Institute’s Interpreter. “It is debatable whether that cost should be repeated by other countries.”

Likewise, Indonesia moved to value-add its nickel production in 2014. It went so far as to restrict exports – triggering a global price spike – while comprehensive new Chinese-owned and operated facilities were being built.

“China also financed supporting infrastructure needed for nickel processing. Many coal-fired power plants, on which nickel smelting depends, were set up in Indonesia through China’s “Belt and Road Initiative” (BRI),” policy analyst Dr Teesta Prakash says in the Australian Institute of International Affairs’ Australian Outlook.

“Before the ban, Indonesia only supplied raw nickel ore, valued at US$6 billion in 2013. By 2022, this figure increased to US$30 billion due to refinement.”

Competitive chokehold

“We should strengthen the production and supply of food and strategic mineral resources, and build a strategic base to guarantee the supply of important primary products for the country,” Chairman Xi Jinping proclaimed shortly before restricting refined gallium and germanium exports in July last year.

Trade restrictions, embargoes and sanctions are nothing new on the world stage.

But China seems especially willing to use its new-found economic superpower status to coerce its customers.

Australian exports of coal, barley, wine and seafood were banned after Canberra suggested an international inquiry be conducted into the source of the Covid-19 pandemic.

In October last year, Beijing imposed export restrictions on graphite. And that followed similar restrictions on gallium and germanium earlier in the year.

It’s just part of an ongoing tit-for-tat trade war with the United States and the European Union. They’ve been steadily increasing restrictions on the export of advanced semiconductors – one last technological weakness China is determined to overcome.

“Together, these announcements have been met with alarm given the dominant role China plays in the production of these minerals, as well as the minerals’ important role in the semiconductor industry and the clean energy economy,” says Atlantic Council think-tank analyst Reed Blakemore.

Left in the dust

“Perhaps the most pressing of these challenges is the global crash in lithium value,” ASPI warns. “Prices of lithium — Australia’s second largest commodity in committed capital expenditure through to 2030, surpassing even iron ore — collapsed in the last 12 months.”

Australian governments have leapt at the prospect of becoming the Western world’s quarry in response to growing concerns over China’s reliability.

Last year, Canberra committed an additional $2 billion in subsidies for miners – and processors – of critical minerals to set up shop here.

The stated goal was to reduce reliance on China and support US attempts to revive its own neglected processing facilities.

But the unfolding metals market price collapse is casting a long shadow over the economic viability of this strategy – without further heavy subsidisation by Western governments.

“Judging from the supply side, Australia enjoys a powerful position in lithium,” adds Dr Zhang. “On the demand side, however, because power is concentrated in a single large buyer – China – this is a vulnerability for Australia.”

That vulnerability is being seen in regional Australia.

The Finniss lithium mine in the Northern Territory suspended operations in January. Other closures are expected to follow.

BHP has written off its Nickel West division in WA as worthless. It’s preparing to suspend operations.

Australian billionaire Andrew Forrest is also shutting down all his WA nickel mines.

Meanwhile, Australian lithium producers and steel refineries are also reviewing their economic viability.

Sovereign tales

“Australia is a leading producer of critical minerals, supplying all ten of the elements needed for lithium-ion batteries, and has the advantage of better environmental, social, and governance (ESG) standards that make it an attractive destination for investment,” argues Monash University Associate Professor Mohan Yellishetty.

But one crucial ingredient is lacking: A homegrown market.

The demise of Australia’s vehicle manufacturing industry and the slow rollout of the green energy transition means poor local demand. And that means multinational manufacturers aren’t interested in building production facilities here.

Another option is to underwrite the construction of large national processing facilities for the likes of nickel, lithium and the other rare earth elements Australia has in abundance.

And these can be “sold” to environmentally conscious markets – such as the European Union – as being far cleaner than their competitors.

But Canberra has, in recent decades, instead been heavily focused on privatising national assets instead of investing in them.

“Policies enacted under President Xi Jinping underwrite China’s undue influence and continue to blur the lines between the private sector and the government in China,” ASPI warns. “It is a political risk compounding the economic issue of overreliance on a single market.”

Jamie Seidel is a freelance writer | @JamieSeidel