Inspired by the late, great Jim Stynes, former AFL player Fergus Watts is now Reach CEO

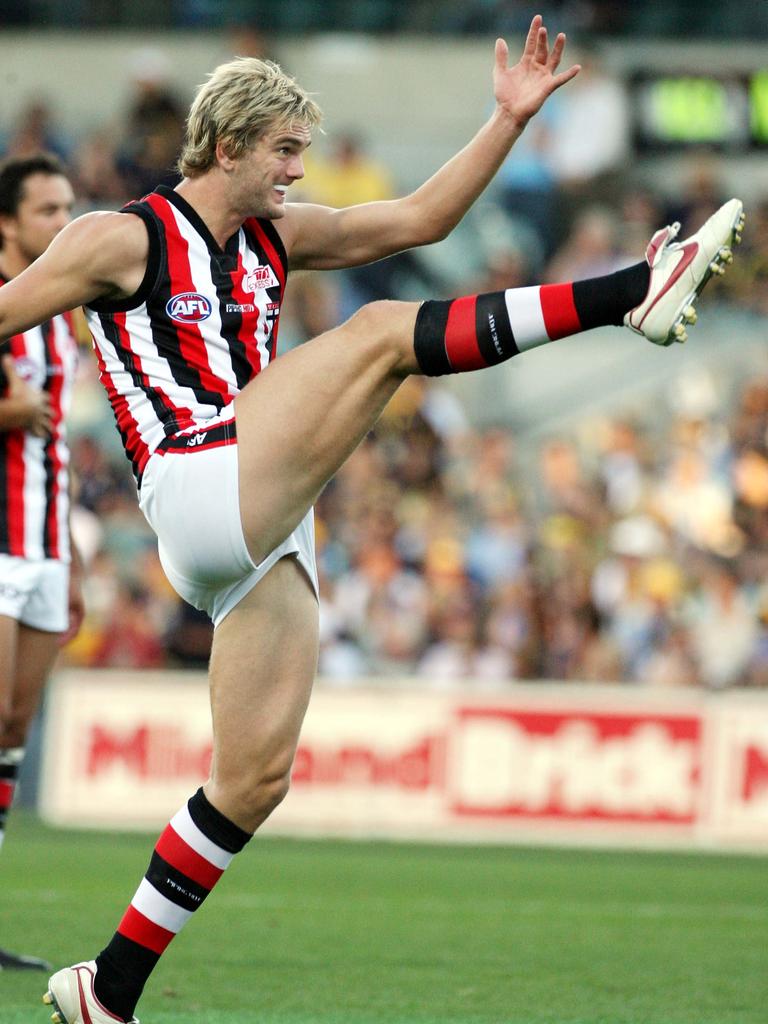

Humiliated by his short-lived AFL career and subjected to booing and abuse from fans, wounded former Crows and St Kilda player Fergus Watts found salvation in Jim Stynes.

Victoria

Don't miss out on the headlines from Victoria. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Fergus Watts was selected at 14 for the Adelaide Crows in the 2013 draft. He played just five games for the Crows over two years, and then one for St. Kilda. And then his career was over. He battled with a career that fell short of his, and others expectations. He recently left his executive role at the marketing agency he founded and has been looking for what is next. He has just been appointed CEO of Reach, hoping to make a difference in the lives of young Australians.

HM: How did you first experience Reach?

FW: As a 15-year-old. I was at Leonda By The Yarra, for a Reach Heroes Day and 400 young people were there as guests. Jim Stynes and Jules Lund were facilitating the day. I fell in love with it from there.

HM: What did you learn?

FW: Firstly, understanding myself better, and secondly, learning through interaction, both personally and through observation.

HM: How?

FW: At the start of the day, I was sitting down, and everyone was very boisterous and carrying on. Jim singled me out of the crowd and got me to stand on my chair. He asked, ‘who are you?’ I really fumbled around for an answer and was embarrassed to say too much, and just top-lined it and sat down. Later in the day he asked me again. ‘Who are you?’ I spoke from the heart and opened up. Jim then made a comment to the room and said ‘do you see what difference a day can bring to a person, and to their life?’ I started off a very defensive, protective, macho man, and by the end of the day, was a more sensitive, giving, empathetic, vulnerable person. The key learning out of that for me was that it was okay to be all of that, and it was much easier to be.

HM: Jim was a visionary and pioneer. What did he hope to do all those years ago?

FW: He wanted Reach to build emotional and social resilience skills in young people through transformative experiences. He wanted it to have the ability to develop emotional and social resilience through a better sense of self, a better understanding of who you are as an individual, and how the decisions that you make in your life come about through acting from ego, or your spirit. That is primarily the work that we do now, 28 years on.

HM: He seemed ahead of his time as a thinker and ‘carer’ of people.

FW: He was. Jim and Paul Currie founded Reach, and pioneered the work. He made it easier for a young person that needed to have a real conversation, to have one, and allow them to understand how and why they are feeling the way they are. And however they were feeling, that it’s OK, and that there are ways to deal with those emotions. That was Jim and Paul’s vision for the place. They were very passionate in making sure that Reach was facilitated in a room of young people before they were considered high risk.

HM: Do you think you would have decided to go back and try to help the youth of today, if you hadn’t had what you described as ‘a big failure, and a public one’, as a football career?

FW: I don’t think so. I think my time, and what I learnt and how it shaped me, particularly after the footy ended, was so important to me. I describe my time at Reach, and my time in AFL football, as ‘the two best university degrees I never had’, having never gone to university. Whether it be getting drafted and dealing with everything that goes with getting drafted as a first-round pick comes wit hits issues, but Reach helped me set my emotional boundariesto help me manage the highs and lows better. I thought it was going to be a 15-year career, but it was an uneventful and disappointing four years. Being able to understand why I felt all the negative emotions I felt was a crucial component in being able to get myself through those incredibly hard times. And because I did, I just felt a bit of an urge to help others now given how much it helped me.

HM: When your career fell apart and ended at St Kilda, who did you have to support you?

FW: My family, and good friends were around me.

HM: Were you able to talk to them?

FW: I was, but I didn’t want to talk about it for a while. I didn’t talk about it. I shut it out.

HM: Too embarrassed?

FW: Yep. And to be honest, I went back to that macho, bravado personality, that doesn’t talk openly as I did when I was standing on the chair in front of Jim Stynes the first time.

HM: The game you love, hurt you?

FW: It certainly didn’t give me what I was hoping it would. I fell out of love with football very hard, and it took me half a decade to watch a football game again. They were incredibly difficult periods for me, dark times, but because of the work I’d done with Jim, I knew I couldn’t let them define me. They have shaped me; it’s helped me learn and grow.

HM: If you went through a career as an AFL footballer a year from now, having gone through all the programs and having understood more, would you be better equipped to have that short AFL career again, and then respond from it? Is that what you’re trying to give people?

FW: Yeah, much better. I’m older, built a business and managed the ups and downs of that, lived overseas, I’m more mature. A mixture of Reach, and having lived through one AFL career, and time since and learnings since, would make another AFL career, or any career, and any career with troubles, much easier.

HM: You really battled at the Adelaide Crows?

FW: I did. I was front page news in Adelaide when drafted, and then getting abused when I was playing poorly or not living up to expectation, and then being sledged on the street because I was leaving the Crows and going back to a Victorian club, I was 19-years-old. I was a kid. The maturity level required to deal with those sorts of things in the moment is beyond the years that these young guys have.

HM: Any positives from your AFL career?

FW: I don’t think I’d be in the position that I’m in my life now, with some skills to be a CEO and having the potential to make an impact on shaping the next generation of young people through the Reach Foundation. I think I am a more understanding leader, because of the difficult times I had in my footy career. Those times haven’t defined me, but they’ve helped shape me.

HM: When you were at the Crows, before you’d even decided to go back home to Victoria, you were being hurled abused at for being an overvalued pick, by the fans of the club you played for, is it true you were spat at?

FW: All of those things started once I decided to leave the Crows. I was spat at on the street, and I used to cop a fair bit of abuse. I remember playing in the SANFL grand final for the Woodville – West Torrens Eagles against Central Districts. There would have been 30,000 people there. I remember being on the ground, and it dawned on me that I was being booed by the entire crowd. The Central fans, and Woodville fans, all together, because I’d announced I was leaving the Crows a couple of weeks before.

HM: Harsh …

FW: Unusual, if nothing else! After the game, we went back to the club, like teams do after grand finals, and we were announced on stage one by one. Everyone applauds the players as they come up. My name was announced by my own club, in front of our supporters, and I was booed there too. I had an old lady come up to me and yell at me in a cafe. I was a 19-year-old kid. At the time, I didn’t really know what to think. I laughed it off, but it has stuck with me ever since. I can pretend it hasn’t, but it has. It hits you deeply emotionally, and it stays around.

HM: You fell out of love with an industry and a game you loved as a kid. How do you get to a point where you are at ease with all the things that were so complicated?

FW: By defining what really mattered. The ability to operate from a deep emotional understanding is important. That’s what gets you through those things. What’s interesting about failing as an AFL footballer is you are deemed ‘no good at football’. I was a first-round draft pick twice, an all Australian under 18, I was in the AFL system, I was a good SANFL footballer and a good VFL footballer. That is confronting, because for your whole life you have been deemed a good footballer, and people know you as that. Then suddenly, because you are at the elite level, and you’re not in the elite of the elite level, you are seen as not up to it. No good. Not quick. Not agile. They are very hard things to get your head around, if you are operating from a position of ego, which we all do. It’s just a question of whether it drives us or not.

HM: Do you watch the footy now?

FW: It took me a long time to, bit by bit, break that ego down, to a point where it wasn’t painful to go to a football game anymore. I remember going to the footy to watch Robert Harvey break the games record for St Kilda, two years after I’d left the Saints. I was so embarrassed walking into the stadium. I thought people would recognise me, which they did. People made remarks as I walked to my seat. I was out of the system then, but I was embarrassed. At the end of the day, that’s all ego, and once I came to terms with that, then football was just another part of my life.

HM: You left football after stints at two clubs, had the time at Reach, and decided to start an advertising agency, which has been successful, and then stepped away as the CEO. To look for more … nourishment, for want of a better world.

FW: That’s a good word actually. I’d been trying to figure out what’s next for me, and there were plenty of things that had come up, plenty of opportunities, but nothing that looked like they’d feed my soul. It makes me feel proud. I feel I have a renewed purpose, that is now focused on giving the next generation of young people tools to go forward. It’s a great reason to get out of bed every morning. I have been involved with this place for 21 years. It’s a special place, with a special place in my heart, because of the people involved in it, the work it does, and the opportunity ahead of us to do it at such a significantly greater scale. I am extremely excited about it.

HM: Who are the people that Reach helps every day?

FW: Most of our work sits between year 9 and year 11 kids. We do some year 5s and year 6s and some young corporates through our program called Wake. That’s our target market of people that we work with.

HM: The needs of the kids are variable?

FW: Absolutely. Young people from high risk environments. Or they might be people like me, who went to a private school, grew up in a great family, and seemed to have it all. Reach is not about solving an immediate problem, it’s about getting young people to better understand themselves. We get them to understand why they are feeling the way they are, to help them make better decisions, to take them from a negative position to a neutral position, or from a neutral position to a more positive position.

HM: If over the next five years you’ve achieved what you wanted to, what does Reach look like, and how is it different?

FW: It’s more diverse, and we are impacting more young people in more diverse ways. We run workshops here, whether they be hero days, school workshops, community-based workshops. Reach will be continually evolving, and continually getting better. That’s one of the core elements of how to impact 500,000 young people a year. That’s our aim.

HM: What is the most prevalent issue you see within the demographic?

FW: It’s a very broad question because it’s relative to the demographic we are working with. Our team was in Alice Springs two weeks ago running workshops for a high risk community that loses one young person to suicide a week. We were up there twelve months ago and went up again two weeks ago. Almost 100 per cent of the young people that we worked with 12 months ago are still in school or employed 12 months later. That is in a community that loses one young person a week to suicide.

HM: Hard to fathom those numbers.

FW: That impact is undeniable and is substantial. We had a young guy two weeks ago who was arrested 10 days prior to our group going up there. He smashed up the school, did a few other things, he came to this workshop, and through the facilitation of our team that was up there, he started to open up. He started to open up about how his brother had died a month earlier, how he was really struggling with the death, and how he now understands that he was using his grief as anger and making bad decisions in his life. Now, through this work, he will endeavour to make better decisions on a day-by-day scenario, by understanding that it’s OK to grieve, it’s OK to feel how he feels. From that one defining moment in this young person’s life, he now has a choice. He can make slightly better decisions day by day. Young people are not given the opportunity to be in a room, and to have those conversations, very often.

HM: How has Covid affected the youth, and what are you seeing?

FW: I don’t believe that Covid has created the mental health crisis in this country, but I believe it has showcased it. If I asked you to run a marathon, and you’d never been for a run before, you’d really struggle to get through. What we have asked young people to do over the last few years is deal with a really difficult situation, that is mentally taxing on every human being. We are asking developing minds, that are 13, 16, 18 years old, to deal with that. I don’t think we’ve given them the skills, or educated them, on how to develop these mental muscles over the last half decade. That’s what Covid is showcasing.

HM: You’ve said, “rather than waiting for mental ill health to manifest, we need to focus on the promotion and prevention of mental health in young people earlier on, by giving them the tools to navigate life’s challenges and thrive”.

FW: It’s the only answer. The federal budget gave a large amount of funding to mental health, and a lot of it went to reactive intervention solutions. The state government did the same. Every dollar spent on a preventive solution saves $5 or $10 from an intervention perspective and a reactive solution. We are on a mission to change the view of society, and if we really want to develop the mental position of young people in this country, to be able to deal with the ever-changing world that they grow up in, which is different to the world we grew up in, we need to educate them now on the skills that they’ll need in five or ten year’s time. That’s where society needs to change its view of what’s important. We need to change our position on what we fund, what we donate to, and where we spend our money.

HM: How do you reckon Jim would be looking at Reach in 2022? Pleased with what he started?

FW: I certainly hope so. The workers and facilitators here are as good as they’ve ever been. One of the cool factors of Reach is we are young people that work with young people. Pretty much all our facilitators are under the age of 25. We recruit crew at 15 or 16, we train our young people, and they go out to start working with young people at the age of 19. There is no other organisation that does what we do from that perspective. Most of the other organisations that do similar work to Reach, have been founded by ex-Reach facilitators. They trained at Reach, they’ve done the work at Reach, and then became too old for our model, and have gone on and built their own business. Similar work, but adults facilitating young people. That is what is unique about the Reach model, and I know that’s something Jim and Paul were especially passionate about. I’d like to think Jim is looking down now and is excited about the future of Reach. He would be jumping up and down, saying Reach has never been more needed in this community than what it is now.

HM: What does Reach need right now?

FW: Funding. We have a proposal to run workshops in Lismore, at the schools, in the flood affected regions. We must get that work funded to be able to deliver the work, because of the commercial constraints on our business. We are not as reactive to those real life situations as we’d like to be and we need to be. The extra funding would see the development of the crew and deeper training of our facilitators, but awareness is the big thing. Awareness, and prevention, is the only long-term solution. That’s what will really change the game.

More Coverage

Originally published as Inspired by the late, great Jim Stynes, former AFL player Fergus Watts is now Reach CEO