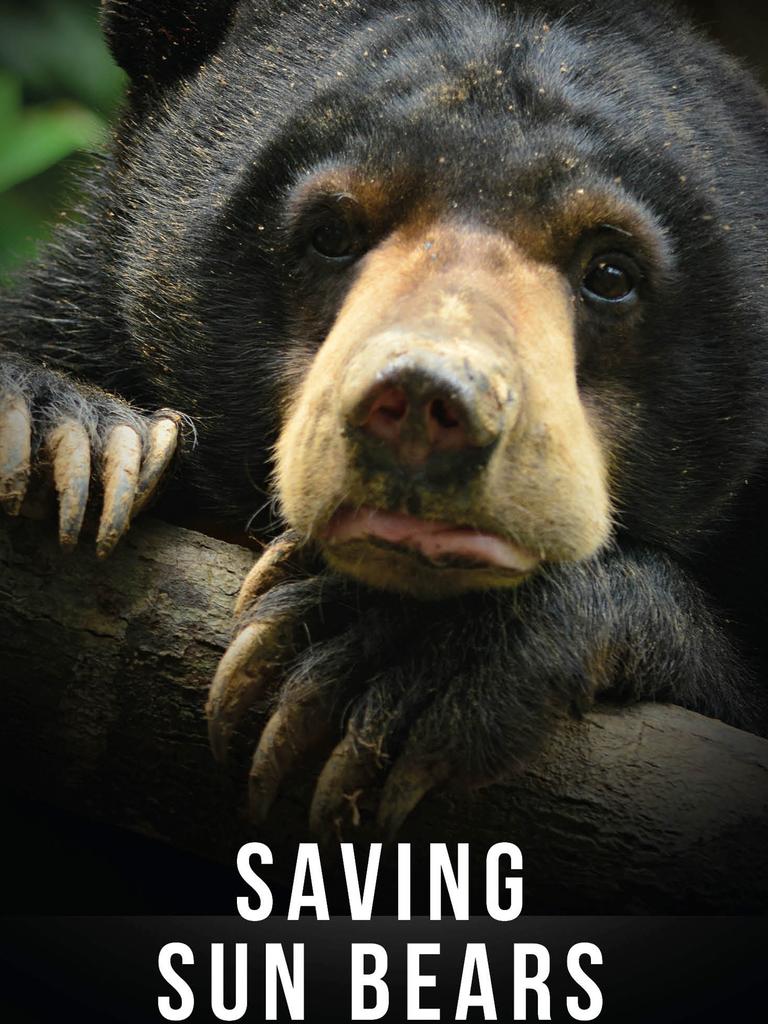

One person really can make a difference

Time is ticking for the sun bear and, unless we halt habitat destruction, it’s likely they won’t be around for my grandchildren.

Opinion

Don't miss out on the headlines from Opinion. Followed categories will be added to My News.

“DO WHAT you do best,” Malaysian ecologist Dr Wong Siew Te said to me when I asked what I could do to help him save sun bears from extinction.

That was way back in 2012.

I had gone to Borneo to tick orang-utans off my bucket list, not knowing a completely different species would become my focus.

Those five powerful words led me on a seven-year journey. I introduced Wong to the University of the Sunshine Coast, which led to collaborative research projects and design projects.

In 2014, I led a student team to create a sun bear adoption program which was launched at Australia Zoo and in Malaysia.

Then in 2016, I asked Wong if I could write his story and the past four years have been spent doing just that as part of my doctorate. The resulting biography, Saving Sun Bears, was launched globally as part of the Sunshine Coast World Environment Day program on June 5.

So, what was it about this charismatic scientist and the sun bears in his care that held my interest for the past seven years?

From the moment I saw sun bears 40m in the trees, swinging from vines, I was captivated. There are far fewer sun bears than orang-utans, themselves classified as critically endangered. Time is ticking for this characterful creature and, unless we halt habitat destruction, it’s likely they won’t be around for my grandchildren.

That’s no idle threat. During the short time I’ve been writing this book, the Sumatran rhino, which shared the same forest, was declared extinct in the wild.

All the 15,000 species of flowering plants, 3000 species of trees, 221 mammals and 420 birds in Borneo rely on each other for survival.

Take the tiny fig wasp, for instance. Without it, there are no figs. No figs, no food. No food, no bears.

This interconnectivity of living things is not unique to Borneo, and if there is something we should take from the COVID-19 pandemic, it is that humans are not above nature.

As the well-worn COVID catchphrase says: “We are all in this together”.

Sun bears are killed for their gall bladders, as the bile is a sought-after ingredient in Chinese medicine.

Orphaned cubs are sold into the illegal pet trade, often in wet markets alongside the quartered bodies of their mothers, and crammed into tight cages close to species they never meet in the wild.

Such mistreatment of wildlife, and the transference of viruses between, probably created the predicament in which we find ourselves.

This virus is not unique and if we don’t stop such practices, who knows how severe the next virus will be.

Even with such alarming topics, Saving Sun Bears is not an apocalyptic narrative.

This is a story of hope. It proves that one person can make a difference — be it Borneo and bears, or the Coast and koalas.

No-one had ever studied sun bears when Wong started researching them in the 1990s. He spent years trekking through dense undergrowth, trying to trap and collar bears to advance human knowledge of the species.

Along the way, Wong came face-to-face with angry grizzly bears in Montana; his car was overturned by disgruntled elephants in Borneo; his field assistant tragically drowned in flood waters; he created the world-class Bornean Sun Bear Conservation Centre; and he was eventually acknowledged as a CNN world wildlife hero.

Wong’s goal is to rehabilitate as many bears as possible, and in 2018, I was invited to become part of a release team.

Under the cool cloak of darkness, we drove two bears to the edge of Tabin Wildlife Reserve: a protected area twice the size of Singapore. As I climbed into the helicopter, a translocation cage was swaddled in a cargo net and hitched below.

The pilot concentrated with every sinew as we flew above the broccoli-like canopy and the bear swung below us. We landed on the only bald patch – a mineral-rich mud volcano cratered by elephant footprints in the middle of the reserve.

Before he pulled the rope to release the trap door on Debbie’s cage, I watched Wong kneel down beside her, fingering the scar she gave him as a cub. “You are back where you belong, Debbie,” he said, “I kept my promise.”

If you would like a copy of Saving Sun Bears, support your neighbourhood bookshop by purchasing through them. Alternatively, order a hard copy, e-book or audio book using major online retailers.

To support BSBCC and sun bear rehabilitation, visit www.BSBCC.org.my or contact author Sarah Pye via www.savingsunbears.com