SUICIDE EPICENTRE: Data reveals Burnett‘s dark problem

AFTER 16 months, a South Burnett family is still searching for answers after losing their 12-year-old to suicide. They‘re just one of many families dealing with the shockwave of grief living in Queensland’s suicide capital.

South Burnett

Don't miss out on the headlines from South Burnett. Followed categories will be added to My News.

SIX young Wondai girls have been left heartbroken, confused and unable to process the grief of losing their big brother Tyson Christensen who took his own life at just 12 years old.

Anna-Maree, 12, Jesika, 7, Sarah 5, Hailey 3, Tayla, 2 and Mikayla, 4 months, are still coming to terms with the tragic loss of Tyson on July 28, 2019.

Just as Tyson's death did, cases of suicide send ripples of grief and confusion through families, friends and the wider community.

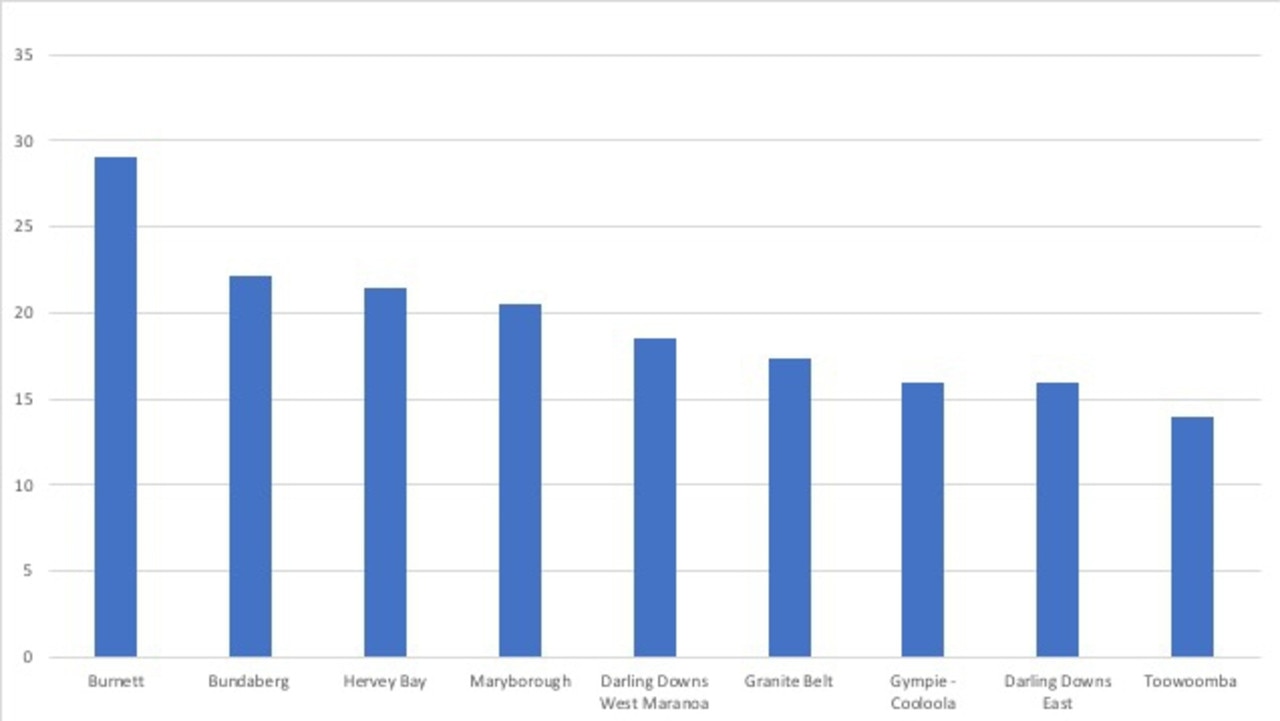

New data has revealed the Burnett is experiencing a constant tidal wave of grief - with the region named in a report by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare as having the highest rate of suicide in Queensland.

Between 2015 and 2019, 67 lives were lost to suicide in the South, Central and North Burnett, more per capita than any other Queensland region.

Residents across the Burnett fight an uphill battle, the small number of mental health facilities that are available are either underfunded or overrun with patients seeking help.

When Tyson passed, child services became involved to help his sisters deal with the grief, however the girls are yet to receive grief counselling despite Anna-Maree and Sarah being the ones who found their brother.

Tyson's mother Lutece Maree Christensen said her daughters have witnessed a lot more than any child ever should.

"They struggle a lot, one has become very emotional and cries a lot. My five-year-old, Sarah and Tyson were like best friends, they did everything together and now she has separation anxiety," she said.

"When I had just had the new baby, her separation anxiety was that bad she was staying with an aunt and they had to call me to reassure her I was still coming home.

"Once I went away in an ambulance and she thought I wasn't coming home like Tyson.

"My 12-year-old is very distant, she is isolating herself. It's been really hard on all of them, more so the three older ones because they know and understand to a certain extent but the younger ones know they miss their brother and don't understand how or what or why."

Mrs Christensen remembers Tyson as a caring, compassionate and adventurous young boy who proudly wore the Wondai Wolves jersey and loved his sisters more than anything else in the world.

Tyson's preventable death added to the tragic statistics, where between 2015-2019 the Burnett region had 29 deaths per 100,000 people compared to surrounding regions like Bundaberg who had 22.1 deaths, Hervey Bay 21.5 deaths, Maryborough 20.5, Darling Downs West 18.5, Granite Belt 17.3, Gympie 16, Darling Downs East 16 and Toowoomba 14.

More than 15,500 people died from suicide across the country during that time period and 3824 of those deaths were Queenslanders.

January and February are the deadliest months for suicides, according to the AIHW, with the most common contributing factors to suicide including a history of self-harm, disruption of family by separation and divorce, relationship problems, the disappearance and death of a family member and legal problems.

Mrs Christensen said Tyson was not taken seriously by mental health professionals and it took months to get help.

"When I took Tyson to the doctors, he said he was having these thoughts about himself and they didn't do anything, it was just a private conversation where the doctor let him know he's got more to live for then how he feels right now," Mrs Christensen said.

"They didn't take him seriously, it took months before we could get him help and I had to just keep taking him back."

It's the lack of access to quality mental health programs in rural Queensland that leads to a spike in suicides, according to Dr Geoffrey Woolcock, a researcher in the University of Southern Queensland's Rural Economies Centre of Excellence and head researcher at Head Yakka.

"We empirically know that there is a severe lack of mental health services in regional Queensland, particularly at the acute end with ongoing stories of mentally unwell patients waiting up to months for telehealth appointments with SEQld-based specialists," Dr Woolcock said.

Associate Professor Gavin Beccaria from the University of Southern Queensland's School of Psychology and Counselling agreed, saying attracting suitably qualified mental health staff in regional Queensland has always been a challenge.

"Issues such as drought, isolation, lack of or unstable work and lack of access to mental health services are just some of the key factors that may contribute to these statistics," Prof Beccaria said.

"There is also a large Indigenous population, unfortunately, suicide rates among Indigenous Australians is tragically too high."

For Mrs Christensen, the loss of her only son has her urging parents to make their children's mental health a priority, especially those living in the Burnett.

"They are just kids and they don't understand what's going on or how they feel but it's not a joke to them they take it seriously.

"For kids they need to talk, find someone they trust and just talk, parents can't help if the child can't tell us what's going on."

Sixteen months on, Mrs Christensen and her family continue to try and cope with the preventable loss of their beloved Tyson.

"His birthdays are obviously always going to be the hardest for us, we are very family-oriented and there wasn't a lot we didn't celebrate," she said.

"When we celebrate the kids were always happy and spoiled so I think the hardest thing would be doing things as a family and missing a family member."

If you would like to contribute and support the family, visit the GoFundMe page here.

If this story has raised any issues for you, contact Lifeline on 13 11 14 or The Kids Helpline on 1800 55 1800.

For a full list of local contacts click here.