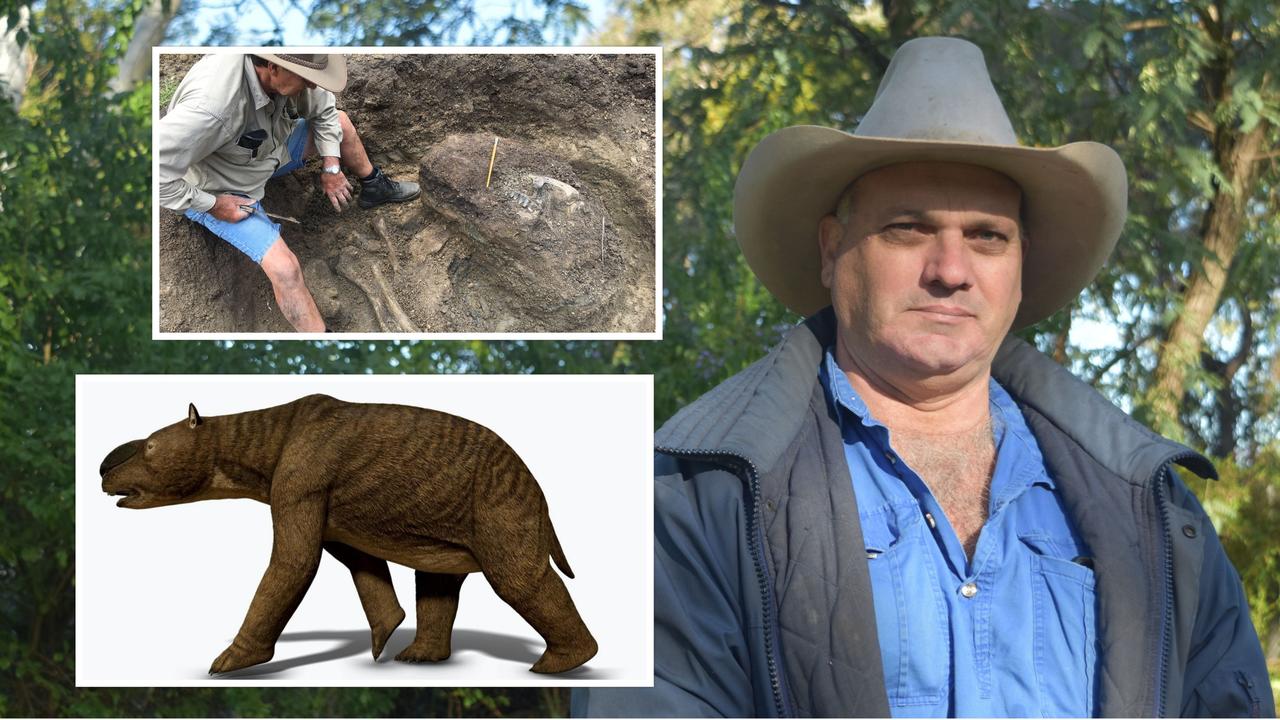

Meat producer Brett Grant and avocational palaeontologists discover ancient marsupial in Dalby

A meat producer and two palaeontologists are fighting to hold onto the remains of an ancient creature the size of a Nissan X-Trail found on the Western Downs, saying losing the history would be a huge blow.

Community News

Don't miss out on the headlines from Community News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

A Dalby beef producer and two palaeontologists are on a mission to retain for future generations the bones of the world’s largest ever marsupial on the Western Downs.

Brett Grant’s first interaction with the ancient bones was in October 2020, when he met with a group of researchers conducting an excavation near his property in Dalby.

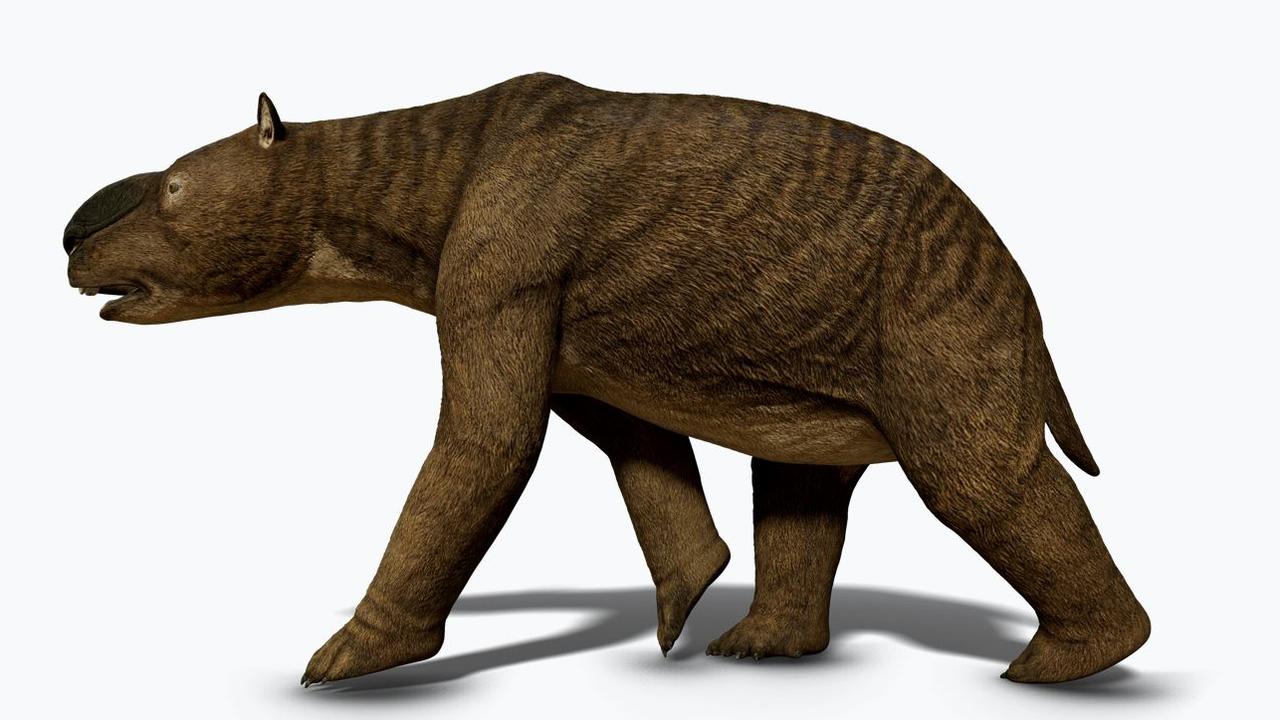

Little did he know, avocational palaeontologists Troy and Skyelar Cox and their colleagues had found the remains of a diprotodon, the largest of all Australian megafauna in history.

“When they told me it was a diprotodon, I had heard of it before, because a friend had actually found a tooth of one in same riverbank several years ago,” Mr Grant said.

Weighing more than two tonnes, the massive marsupial existed from about 1.6 million years ago until its extinction 44,000 years ago.

It resembles a giant wombat, and would’ve stood almost two metres high, or the size of a Nissan X-Trail.

Mr Grant said the marsupial’s skull, neck, shoulder blade, and front leg was exhumed from the dig.

Both parties now want the fossil stay in Dalby instead of going to Brisbane, to inspire the next generation of palaeontologists.

“This could be something good for the local community … something for parents to take their kids to and show them the history of the area,” Mr Grant said.

“It just seems absurd for me for people to have to do a seven-hour round trip to Brisbane to see a fossil that was found 15 minutes from town.”

Mr Grant went to Western Downs Regional Council to see if they would help keep the fossil in town, but was told they didn’t have the capacity to house it.

A council spokeswoman said it was due to the significant and fragile nature of the fossils.

“They require expert handling, assessment, and specialised storage, which is not something council has the expertise or facilities to manage,” she said.

“Council, like Mr Grant, wants to see these fossils preserved correctly to ensure they can be admired and enjoyed for time to come.”

Palaeontologists Mr and Mrs Cox said for the fossil to be properly cared for and researched, it needed to go to the Queensland Museum.

“With dating, it’s quite expensive to do, and they only do it for significant fossils,” Mr Cox said.

“None of that research can happen until it’s in a public institution … it can’t be owned by an individual or a council, it has to be donated.”

Mr Cox said if it was donated, it could be given to Dalby on a long term loan, similar to the finds in Richmond in Northern Queensland.

“The onus then would be on council to prove they could secure and manage the property collections for future generations,” Mrs Cox said.

“Keeping a fossil isn’t just about putting it on the shelf, as it will continue to deteriorate over time and needs maintenance.”

Mr Grant had trepidations towards donating the find, and believed there was a chance if he gave to the Queensland Museum, there was no guarantee it would return to Dalby.

“Once you hand it over, you have no control over it, there’s nothing to say that it won’t just stay in a warehouse,” he said.

“It could possibly be lost to the local area, and stay in a storage box forever.”

The Queensland Museum wouldn’t confirm that a community could retain specimen if it was donated, with palaeontologist Dr Scott Hocknull instead saying they would help them better understand the requirements and “obligations” involved in displaying the find.

“The daily tasks of museum experts include the painstaking process of fossil preparation, conservation, collection management, curation, research and display of fossils as we adhere to international museum standards and scientific codes of practice,” he said.

For Mr Cox and his wife, they wanted the best outcome for the fossil.

“Our side isn’t to send it off to Brisbane and have it stay there, it’s to have everyone happy and a winner,” he said.

“It really is an important find and shouldn’t be lost to science, or the people of Dalby.”

More Coverage

Originally published as Meat producer Brett Grant and avocational palaeontologists discover ancient marsupial in Dalby