Opinion: What determines if a country is prone to violence

A nation’s penchant for violence is most likely found in the mindset of its people, writes Paul Williams.

Opinion

Don't miss out on the headlines from Opinion. Followed categories will be added to My News.

The attempted assassination of once and possibly future president Donald Trump is yet another ugly stain on the long-bloodied fabric of a violent American political history.

Regardless of partisan politics, any decent person can only condemn this horrific event. The image of a bleeding Trump was shocking to say the least. If he’d been murdered America could have easily plunged into something akin to civil war.

Sadly, though, the United States – born in revolution in 1776 with the firearm as its midwife – is no stranger to (especially gun) violence. Last year alone there were more than 600 mass shootings.

Already damaged by a civil war that killed hundreds of thousands over the issue of states’ rights, American history bears the assassination of more than 50 politicians. Four have been sitting presidents: Abraham Lincoln in 1865, James Garfield in 1881, William McKinley in 1901 and John F. Kennedy in 1963.

There have been many more unsuccessful attempts, including Teddy Roosevelt, shot in 1912, and Ronald Reagan, shot in 1981 – not to mention the numerous occasions when plots were foiled and guns misfired.

But these terrible moments of extreme political violence overseas can be opportunities for Australians. We should take these opportunities to be grateful we live in a country where political violence is exceedingly rare. Indeed, if there’s so much as a scuffle between party workers at a polling booth on election day, it’s likely to be reported on that night’s television news.

But we have, of course, had our own shameful moments. In 1868, an Irish republican shot and wounded Queen Victoria’s son Prince Alfred, and in 1966 a mentally ill man shot and wounded Labor Opposition leader Arthur Calwell. We’ve also seen MPs bashed, and one, New South Wales MP John Newman, murdered in 1994.

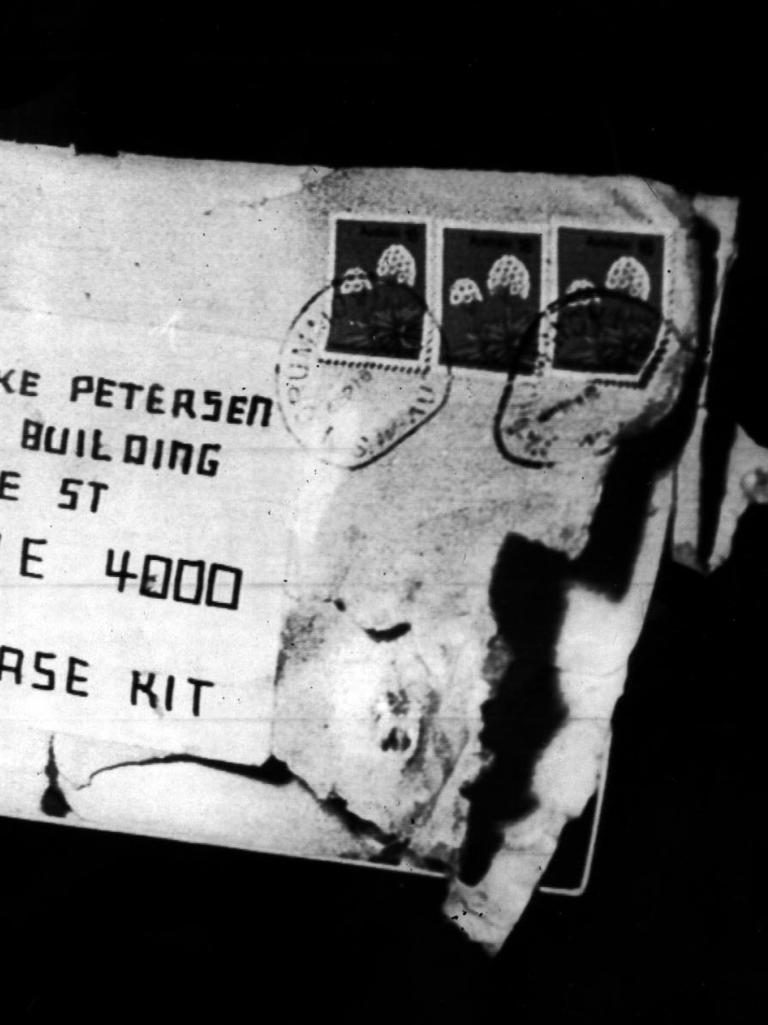

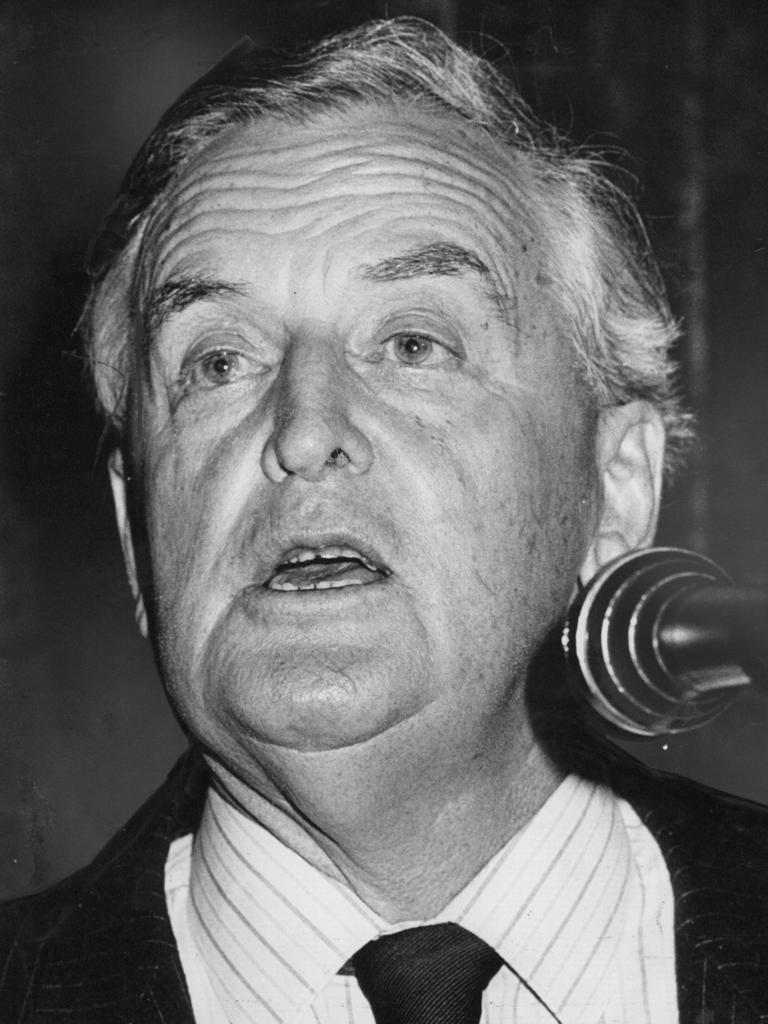

Even in Queensland, a letter-bomb posted to Premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen in 1975 missed its intended target but seriously injured two office workers.

Compare Australia with many a self-described democracy where polling day sees an “election toll” – the number of people killed in political violence – in the same way we publish holiday road tolls. For too many nations, violence has been normalised as part and parcel of a local political culture.

Some historians believe the way a nation is birthed – by peaceful transition of power or via violent revolution – will steer its fate. That would certainly explain the brutality of Russian politics, from Lenin to Putin, since that country’s 1917 revolution. But republican France was also borne of bloodshed in the 1790s, and it suffers little of the violence we see elsewhere.

A nation’s penchant for violence is more likely found in the mindset of its people, even those long exposed to democratic norms and practices. In short, there are three types of “civic” minds: those who believe in power sharing (democracy and pluralism); those who believe in authoritarianism (dictatorship); and those who are apathetic and leave politics to others. Clearly, the second and third varieties are the most dangerous to democracy.

But it also explains why the United States – long held up as a paragon of democracy – is now listed as a flawed democracy where so many Americans embrace the strong, even dictatorial, leader.

And I’m not just talking about Trump. Americans have long supported presidents happy to stretch their constitutional powers. Indeed, Andrew Jackson in the 1830s, Lincoln in the 1860s, Woodrow Wilson in the 1910s, and even Franklin Roosevelt in the 1930s and 1940s, were all accused of being dictators. Lyndon Johnson and Dick Nixon also threw their weight around in the 1960s and 1970s.

In Australia, which received its nationhood on January 1, 1901, not through gunshot but via a simple Act of the British Parliament, too many of us are of the third civic type: the apathetic person who thinks that, no matter who’s elected to parliament or which party forms government, everything will essentially remain the same.

But that’s egregiously false. As former prime minister Paul Keating reminded us: “Change the government and change the country.” The corollary is that to change the country is to change the people, and their future.

Australia has been largely immune from political violence. But, in a society increasingly polarised – fuelled by voters consuming crooked news and increasingly mistrustful of established institutions like parliament and the judiciary – there’s no guarantee we will be forever safe.

A vigilant democracy requires vigilant voters. Don’t let apathy steal our democratic future. Get involved in civic affairs, and thank your god we live in Australia.

Paul Williams is an associate professor at Griffith University

Originally published as Opinion: What determines if a country is prone to violence