Simon Holmes a Court’s rise from billionaire’s son to mass political influencer behind Climate 200

The son of Australia’s first billionaire now exerts huge influence on politics. How ironic that Simon Holmes a Court’s dad made a fortune from coal, oil and gas – and he’s trying to stop them.

Federal Election

Don't miss out on the headlines from Federal Election. Followed categories will be added to My News.

It’s funny how if his father hadn’t made so many millions from coal, oil and gas, we wouldn’t know the name of the son trying to stop them now.

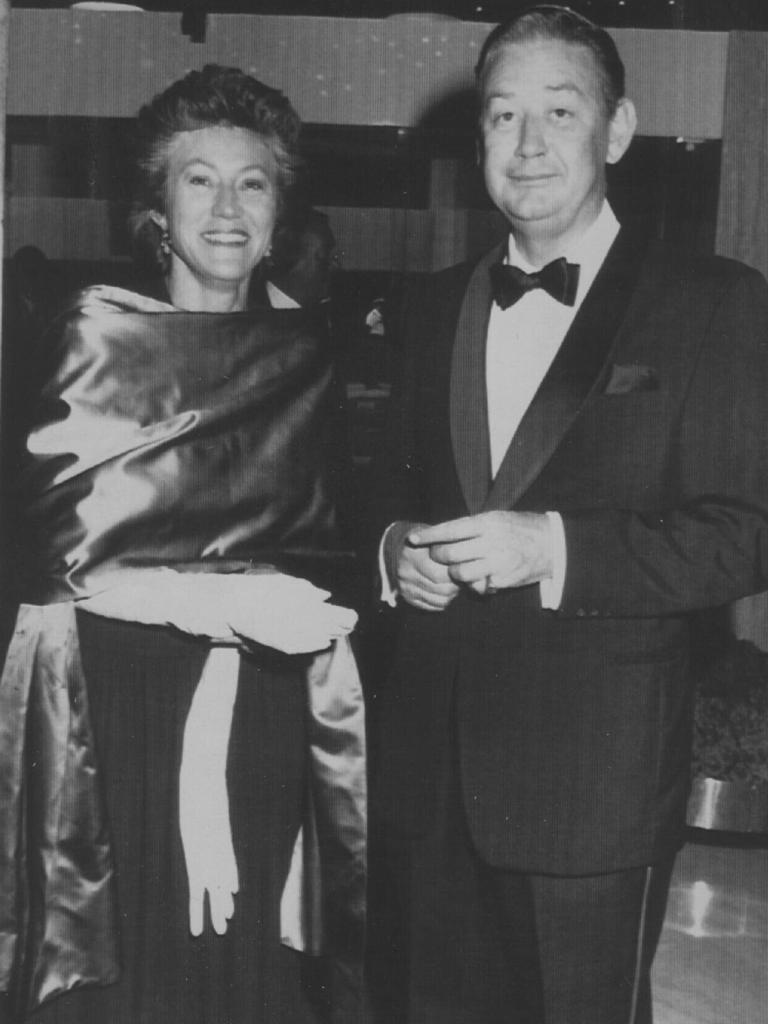

Long before the existence of Climate 200, the Mr Holmes a Court written about in the media was a classic-car and art collector, champion racehorse breeder, media baron and investor tycoon, remembered undeniably as a genius, Robert Holmes a Court.

He was a tall Johannesburg-born, West Australian, part of the British aristocracy, with his cousin being the sixth baron of Heytesbury, who began with a law practice “that gave fast service to mine operators” and worked his way to the rich list buying 1500 shares in a coal mining company.

It became Bell Group, which included “a portfolio of investments in minerals and petroleum”, reported in an interview in Forbes as growing 16-fold to $767 million in a mere 18 months.

Coal, oil, petroleum, and gas investments helped power a growing collection of Rolls Royce cars and Monet paintings.

This immense resource wealth paved the way for interactions with global superstars.

It allowed his wife Janet to gift An Aboriginal Dreaming to Yoko Ono, whom she met when her husband was negotiating sales of the rights to all the Beatles music. Michael Jackson received Aboriginal art from Janet, an avid art collector and theatre landlord.

Prime ministers and opposition leaders alike would run to Robert’s call. He was not just a wealthy magnate; he was the original influencer.

As Robert acquired racehorses, cars, houses and art, “The circle of acquaintances became more elite, and Janet had less time to mix with ordinary people”, Janet’s friend and official biographer Patricia Edgar wrote.

“In three days they bought $35 million (of art) including works by Claude Monet, Henri Matisse, Pierre Bonnard, Berthe Morrissey, Maurice de Vlaminck and Vincent van Gogh”.

I found Janet’s biography at a Lions Club Book Sale in Tamworth for 50 cents, while picking up a haul of historical and political books for when I need to file my column from the heart of the New England Renewable Energy Zone when the power goes out, as it does now despite being surrounded by wind and solar, which Climate 200 says we can power the nation on.

As others have been informed by a traineeship at McDonalds, Climate 200 convener Simon Holmes a Court has been informed by an esoteric exclusion of the rituals of a regular upbringing.

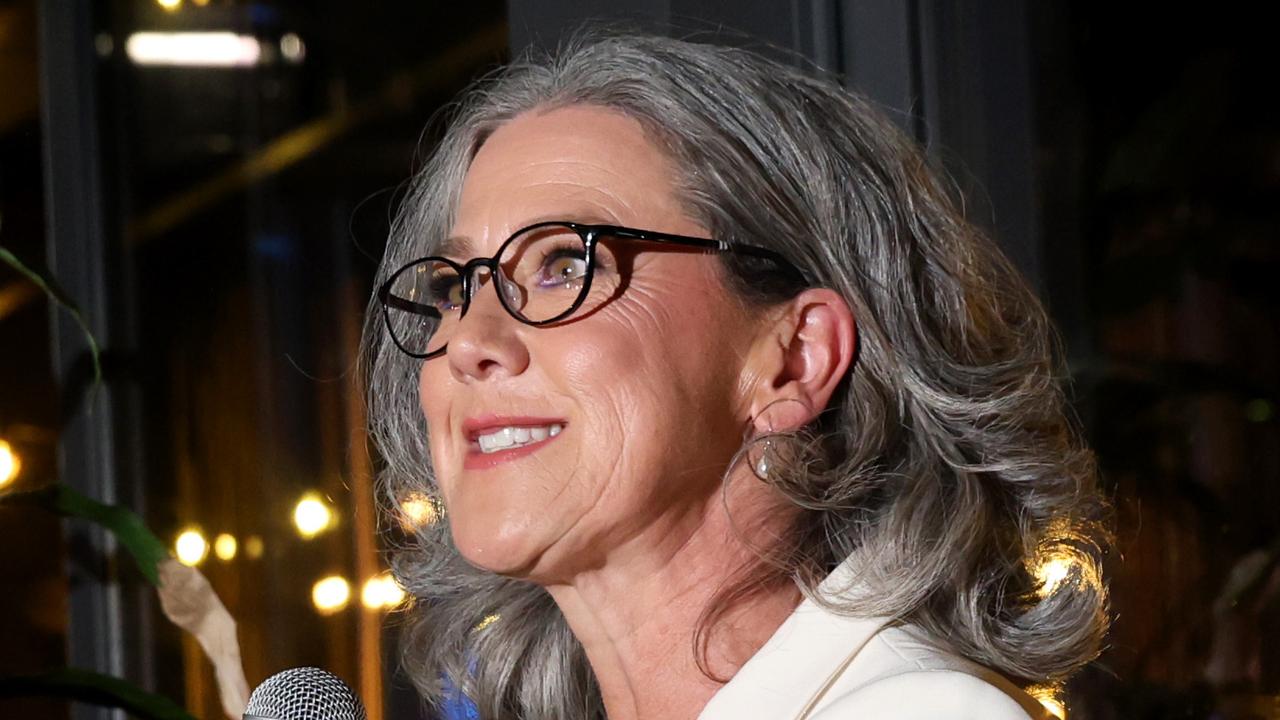

Today, the son of Australia’s first billionaire is a mass influencer on Australian politics. When he isn’t asking for donations to his third-party fundraising vehicle, he is writing books about it, appearing on podcasts, the National Press Club and the ABC.

In one experiment, on the Uncomfortable Conversations podcast, he talks about building an off-grid house in regional Victoria and deciding not to bring powerlines because “they would have gone across our view”.

Yet, unashamedly, his promotion of the country’s transition to wind and solar imposes hundreds of thousands of kilometres of high-voltage transmission lines from wind and solar developments across farms.

This is an opinion shared by the MPs he directs funding to such as Warringah MP Zali Steggal who decries the suggestion of wind turbines in her electorate but lauds it when they are out of sight.

He funds inner-city MPs who fight gas projects hundreds of kilometres away from their seats but advocate for another form of environmental destruction by supporting those who build wind and solar farms, the new developer de jour.

It is the essence of the politics of the elite.

QUESTIONER TOLD ‘DON’T BE A DICK’

Last week Climate 200 convener Simon Holmes a Court was in the front row of a Brisbane theatre, addressing a coterie of loyal listeners, some toting a glass of champagne, oblivious to the panorama they were painting.

A 24-year-old Barclay McGain asks why, if renewables are so cheap, the cost of power keeps going up.

“We are here tonight in a luxury cinema with our champagne flutes,” he points out.

His clip posted by @Chriscoveries goes viral after his ejection, not so much because of McGain’s persistent questioning, but Holmes a Court’s response: “Don’t be a dick.”

The Climate 200 fundraiser, who soared to mass influence following the 2022 election, relishes strangers who agree with him and is quick to pile on the pejorative when they don’t.

Those who believe in hydrocarbons for affordable power are “delusional” or “trolls”. Nuclear advocates are “living in fantasy”. Those trying to tell him our side of the story are a “liar” or “corrupt”.

Those who do not believe 100 per cent renewables in Australia will work are “gadflies”, “geese” and “cockroaches”.

Some commentators are shut down with legal threats, a weapon favoured by the wealthy. At the same time other rich-listers, even those deeply invested in coal and mining seem to be spared the same character assassination.

Physicist Aiden Morrison, who warns of blackouts or bill shocks, was labelled a “troll” working for a “junk tank” (CIS) and blocked on X by Holmes a Court, while carbon-emitting private jet owners like Mike Cannon-Brookes is a “rock star”. Others, like engineer Rob Parker, were cancelled after Mr Holmes a Court posted: “seriously @EngAustralia? you’re hosting an anti-renewables event for @nukeforclimate?”.

But Holmes a Court rejects claims of online bullying.

Instead, he repeatedly refers to being bullied himself by nuclear experts, physicists, and conservative commentators employed by News Corp, like he was bullied at his exclusive private school Geelong Grammar, where his nickname was “BHP”.

BULLIED AT SCHOOL

After growing up near the beach in a mansion in one of Cottesloe’s prestigious addresses in their early life, Simon was sent to the most exclusive private school in Australia, Geelong Grammar.

This coincided with a period where BHP was labelling Robert a “greenmailer”, an investor who buys up shares in a company to threaten a hostile takeover, forcing the target to repurchase its shares at a premium.

According to a biography on Janet Holmes a Court by Patricia Edgar, “Simon’s nickname in school, which he hated, was BHP.”

Ms Edgar details the horrific bullying of the young Simon, “beaten repeatedly”, whipped with an inner tube from a bike tyre, “and if he moved, the whipping would continue”.

It’s not fair when the big kids pick on the little guys, like with this energy “transition” plan in which Climate 200 proposes tax incentives that effectively disadvantage the most financially disadvantaged seats in Australia, where cement suburbs tell us we must cut down our bush and industrialise our farms to fix the environment, where people who started from nothing and worked to own a small block are pulverised.

The transition Climate 200 proposes would have the effect of tying regional Australia to the whipping chair because we cannot fight back. And if we move we get hit again.

In his posse are politicians, media outlets and a glamour set of wealthy individuals with idle time. A cause that comes from a club few can afford membership to.

CRAVED DAD’S ATTENTION

While commentators in the media so often call him the billionaire’s son, Robert Holmes a Court died intestate when Simon was just 18 years old.

It would not be too much of a stretch to suggest Simon’s politics are more influenced by Janet then Robert, or that it’s a reaction against Robert.

It’s challenging to read Janet’s story and not empathise with her and her young children, especially young Simon, left in the mansion at Cottesloe “with carers” while his mother bent to his father’s every whim.

“Simon and Paul would remain in Perth with carers ... without structure or discipline”, Ms Edgar wrote.

The portrait offers vignettes of a child craving attention from a father like most children would.

Young Simon wanted a go-kart for the local race. Instead of his dad, it was a Bells Group “employee named Jimmy” who helped Simon “build the go-kart to beat all go-carts”.

“But when it came time to take it to school, he felt really embarrassed.”

In an excerpt in the book, Simon said: ”Because everyone else had fruit boxes they had knocked together with their fathers, and in a way, my father had helped me knock mine together, but in a very indirect way, he gave me the run of the Bell Group odd jobs man and his resources.”

It also details how the “left-wing” background of Janet’s family came in handy for Robert’s business deals.

She had grown up in the Cold War when “socialists like her parents were vilified”.

“Janet was there when Robert dealt with the unions. Her background was a useful foil. The unions regarded Robert with great suspicion, but having a wife with a very left-wing political background could not be all bad,” Edgar wrote.

MUM’S RISE TO PROMINENCE

Not only did she campaign for the Republic, she was supposed to be, according to polls taken at the time, Australia’s first president.

The WA’s Sunday Times ran headlines “Janet Call”, reporting that in West Australia, she was favoured for Australia’s first president, while a national poll had her come in fourth place, under her old friend Paul Keating.

“Janet’s name was floated by supporters as a more appropriate and appealing leader of the Australian Republican Movement than the abrasive Malcolm Turnbull,” the book said, as she travelled Australia arguing for a new nation.

It was not to be. And Janet wrote her own opinion on the issue.

“Too many of the nation’s silent majority allowed the rhetoric of a committed few to wash over them, or accepted without question both of reason and sophistry which played on their natural instincts of conservatism and fear of change,” Janet observed at the time.

CLIMATE 200 AND THE TEALS

While Simon Holmes a Court had initially been a member of Kooyong 200, a subscriber based third-party fundraising vehicle for the former Liberal Treasurer Josh Frydenberg, Janet Holmes a Court was never a fan of the Coalition.

Prior to the 1996 election, her old friend Prime Minister Paul Keating announced she would be made Centenary of Federation Council chair, which failed to eventuate when John Howard was elected PM instead.

In 1996, when asked about the Howard government’s election win, Janet said: “If you’re in a democracy, you have to expect government to change. What disappointed me was the success of racists and bigots.”

Her son’s organisation has emerged as the greatest threat to the Coalition, using the third-party fundraising instrument.

The major parties despise it because Climate 200 is not subjected to the same scrutiny as political parties by the electoral commission.

One key difference is that the amount donated to Climate 200 is tax deductible instead of a political donation, which is only tax deductible up to $1500.

Climate 200 discloses where the money comes from but not where they spend it.

There’s no public disclosure or register of interests of a third-party fundraiser convener like an elected MP, their families, or even senior political staff in a ministerial office.

The Teals say they aren’t centrally controlled in joint press conferences where they call for more wind and solar. Advertisements for a so-called independent in Cowper are identical to that for a different independent in Curtin on the other side of the country, with evidence of consolidating their media buy.

They say they are not a political party but a movement with one influential figure who says he is not an influencer.

Without Robert Holmes a Court’s coal and oil riches, Simon might have ended up just another ecowarrior lost in the crowd. Fossils do fuel fame.

More Coverage

Originally published as Simon Holmes a Court’s rise from billionaire’s son to mass political influencer behind Climate 200