Modelling shows 80 per cent of Australians need to stay home to reduce coronavirus infections

Australia won’t succeed in driving down new coronavirus infections unless 80 per cent of people stay home, new modelling shows.

News

Don't miss out on the headlines from News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

The importance of Australians staying at home has been backed by new modelling that shows at least 80 per cent of people would need to quarantine themselves to have any impact on reducing new infections.

Professor Mikhail Prokopenko of the University of Sydney said the findings appeared significant enough to release the results straight away, before they had been peer reviewed.

Prof Prokopenko is Director of the Centre for Complex Systems, which specialises in studying how small fluctuations can create larger cascading effects.

The Centre for Complex Systems along with the Marie Bashir Institute for Infectious Diseases and Biosecurity, both located at the University of Sydney, created a model that replicated Australia’s population using data from the Census and the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

This includes creating about 24 million “agents” to represent individual Australians with similar ages, homes and workplaces.

“It is very close to the real distribution of real Australians,” Prof Prokopenko told news.com.au.

Researchers added the epidemiological characteristics of the disease and traced how the infection spread depending on what was known about its transmission rates and other probabilities.

It simulated the effect of different scenarios including the timing of travel restrictions and social distancing measures.

Prof Prokopenko said the model showed there would be a staggering amount of infections if no restrictions were introduced to slow the spread of coronavirus.

“It reaches 50 per cent of the population,” he said. “Which is more than 11 million people.”

While 80 per cent of these people will not even know they have the virus, statistics indicate about 5 per cent would develop severe symptoms and require intensive care treatment.

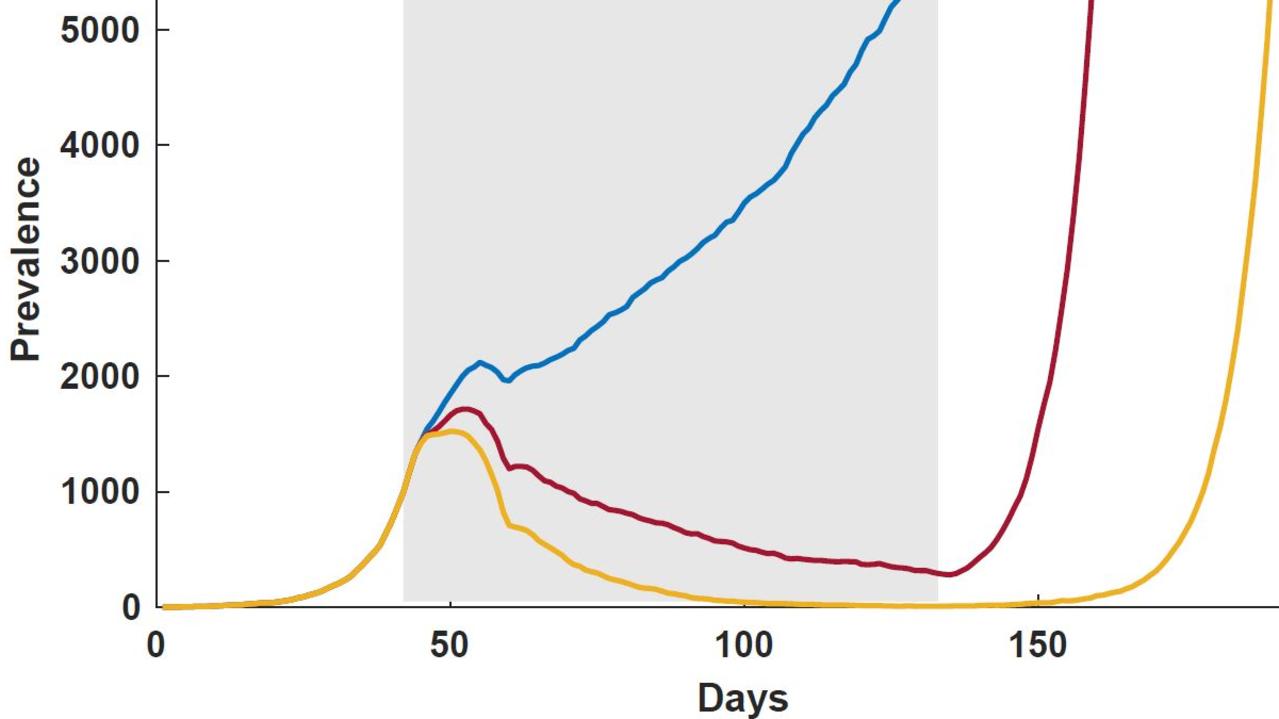

Prof Prokopenko said their model showed “social distancing” must be practised by at least 80 per cent of Australians to bring down cases. Even if 70 per cent of people stayed home, infections would still continue to rise.

“If there is a half hearted 60 or 70 per cent, it doesn’t bring the numbers down. Cases still climb up, just slower,” Prof Prokopenko said.

“70 per cent (social distancing) would be just wasted, if you had 80 per cent, at least we would gain something.”

At least 80 per cent of the population must stay home for the infection to be brought under control, with new cases dropping to about 100 a day within four months.

The spread could be contained in 13 weeks if eight out of 10 people stayed home.

“There is a big divide between 70 and 80 per cent,” he said.

However, the effects would not be permanent, and infections could start to rise again after restrictions were lifted.

RELATED: Coronavirus updates, latest news and death toll

RELATED: 30-year-old in intensive care in Victoria

DRIVING DOWN INFECTIONS

Prof Prokopenko said social distancing didn’t just mean staying 1.5 metres away from someone, it meant people had to stay at home. They could still go out for a walk or to get groceries (as infrequently as possible) as long as they didn’t interact with anyone.

Prof Prokopenko said the measure worked if 80 per cent of Australians stayed home, or another way to approach it, would be if people stayed home 80 per cent of the time.

He gave some examples of what this could look like.

“If there is a family of five people, on any given day, four out of the five must stay home and one could go to work as normal,” he said.

“You could rotate the person allowed out, and it may even be possible for two to go out in one day, but then you must stay home other days.

“If you have a family of three, one person could go out four times a week.

“Or just imagine you get four tickets a week (to go out), then you chose how to use your ticket.”

He said it was more difficult to calculate this for a single person but essentially it meant they could only go to work once over a period of five days.

SHORT-LIVED IMPACT

However, even if 80 per cent of Australians practised social distancing, Prof Prokopenko said the disease would still not be eradicated, and once social distancing measures were relaxed infections would again begin to rise.

“People will still be able to transmit the disease, it just buys us three to four months more to improve health services,” he said.

Making the restrictions more strict and placing them on 90 per cent of the population, also wouldn’t eradicate the disease, according to the model.

But it would drive infections to very low numbers of about 10 cases a day within three months.

If Australia was to be able to get cases to zero it may be able to control the virus as long as strict controls were placed on overseas visitors, such as forced quarantine for at least 14 days.

However, other experts have warned that Australia’s time frame for taking dramatic action to force down infections with the aim of eradicating the disease is fast running out, and may no longer be a viable option.

RELATED: Australia has 48 hours to decide its virus strategy

RELATED: Tough choice Australia faces could prevent ‘economic yoyo’

IT’S UP TO US TO DO THE RIGHT THING

Prof Prokopenko said the outcomes also relied on restrictions being followed by the public and this did not appear to be happening so far.

“I’m not seeing that,” he said. “(Government announcements) have reduced the number of people in the streets but not to (the level) that’s required.”

Prof Prokopenko said any delay in introducing or following restrictions would mean they would have to remain in place for longer.

Although it was not included in their paper, Prof Prokopenko said the model appeared to show that for every extra day’s delay, the period of restrictions would need to be extended for an extra five to seven days.

“This is not just about government policy, it’s about compliance,” he said.

“I easily understand that young people feel invincible but it’s not asking that much – three months of sitting at home 80 per cent of the time is not that draconian,” he said.

While many people had concerns about their wealth and livelihoods, Prof Prokopenko said Australia was facing a moral choice.

“You are talking about a cohort of over 65s who have very little chance of survival if they get the disease during the peak (of virus infections) and systems aren’t able to cope,” he said.

“We are buying time, making some sacrifices but we will save vulnerable people, that’s a no-brainer to me.”

NO WHERE NEAR WHAT’S REQUIRED

Prof Prokopenko said researchers could not tell for sure what Australia’s current measures were equivalent to, but his guess was that around 50 per cent of the population were currently in social isolation.

“We are no where near what’s required,” he said. “It has to change – yesterday or the day before yesterday – we’re losing time.”

“If we’ve lost another day, that means we’ve lost another week at the end of it (the restriction period).”

He said bringing down the numbers of coronavirus cases was difficult because of its long infectious period.

People recovering from coronavirus are infectious for about two weeks, compared to the much shorter flu recovery period of about five days.

“That’s what makes it so difficult to eradicate,” he said.

Prof Prokopenko said governments appeared to be moving in the right direction and were obviously acting based on medical advice.

“Some time has been lost in introducing the travel bans especially for Iran and Italy but what’s done is done,” he said.

“Now it’s hoping these tougher measures will be explained to people, and they need to buy-in to them.

“It’s even less about what the government says now, it’s about what we do ourselves.”

SENDING CHILDREN TO SCHOOL

The issue of whether children should be going to school has been controversial but Prof Prokopenko said the modelling appeared to support keeping them open.

Ironically, sending kids to school appears to be a way of social distancing them from adults in their households.

“They interact with others at school but because children are so asymptomatic and have less severity (in symptoms) that seems to not be impactful on the disease’s spread,” Prof Prokopenko said.

It’s a different story for the flu, which sees children act as “super spreaders”.

“That’s why keeping children in school is probably OK,” he said.

However, keeping schools open may be more of an issue for teachers, who may get the virus from students.

When it comes to the benefits of closing schools, Prof Prokopenko said the model showed it delayed the peak of the virus by a couple of weeks. This came at the expense of slightly more children being infected with the virus at its peak.

Closing schools also seemed to have a positive impact on the spread of the infection, equivalent to an extra 10 per cent of social distancing.

Prof Prokopenko said closing schools, combined with 70 per cent of the population social distancing, may have the same benefit as if 80 per cent were social distancing.

However, he said it wasn’t clear how rigorous this result was as a 10 per cent difference might easily disappear if other factors they had not calculated were taken into consideration.

“We’ve not got full confidence that it’s something that would happen in reality,” he said.

“We’ve not investigated the full range of parameters because there is so many.”

However, Prof Prokopenko was confident about the benefits of getting 80 per cent of Australians social distancing compared to 70 per cent, as the difference sent the results off on totally different trajectories.

“I could say it is established,” he said.