Coronavirus: Australia has 48 hours to decide which path to take

Australia’s been left in the dark about the path authorities will take on the coronavirus pandemic, but one expert says there’s just 48 hours to choose.

Australia has 48 hours to decide which pathway it is going to take on the coronavirus pandemic, an expert says.

Tony Blakely, professor of epidemiology at the University of Melbourne, told news.com.au that the move to shut down pubs, cinemas and other businesses today had happened either too quickly or two slowly depending on what Australia was trying to achieve.

“It depends on what the endgame is and we haven’t been told,” Prof Blakely said.

“We have 48 hours to be really clear on what the societal goal is.”

State and federal governments appear to be divided on what to do, with conflicting messages around the operation of schools and the closures of public spaces.

Prof Blakely said Prime Minister Scott Morrison had appeared to be getting good advice since Tuesday on taking one pathway – to “flatten the curve” – but states appeared to be moving in a different direction, telling parents to keep their kids at home for “practical reasons”.

“Not closing schools yet is excellent advice if you’re aiming to flatten the curve,” Prof Blakely said.

“But state premiers are behaving as if they are ‘eradicating’ the virus by ramping things up.

“You can’t do two things at once.

“They have not been clear. If we are going with eradication, we need to ramp up measures. If we are going to ‘flatten the curve’ then we need to chill a bit.”

TWO CONFLICTING OPTIONS

Australia faces two options – “eradicate” the coronavirus or “flatten the curve”.

“Eradication” would involve a total lockdown of Australians in the hope of squashing the virus within two to six weeks. Once the virus was gone, Australia’s economy would operate separately to the rest of the world for 12 to 16 months while a vaccine was developed.

Wuhan in China appears to have been successful in taking this option, which Prof Blakely said was an extraordinary achievement, but Australia would not be able to enforce some of the draconian measures used there. It would have to consider things like training university students in contact tracing if it was serious about this option and forcing returned travellers to stay in hotels as part of strict quarantine measures.

RELATED: Coronavirus live updates, news and death toll

RELATED: All your coronavirus questions answered

“It’s not easy but it is achievable,” Prof Blakely said. “But if that’s the option then we haven’t acted quickly enough.

“We could still pull it off but it’s not a done deal. It might possibly be more of an option for New Zealand at the moment, which is a week or two behind Australia in its infections.”

The other option of “flattening the curve”, which most other countries are trying to do, involves governments gradually closing businesses and other community gatherings to help the health system cope with a rise in infections.

It basically slows down how quickly people get infected so it takes longer to reach herd immunity, which is achieved when 60 per cent of the community is infected.

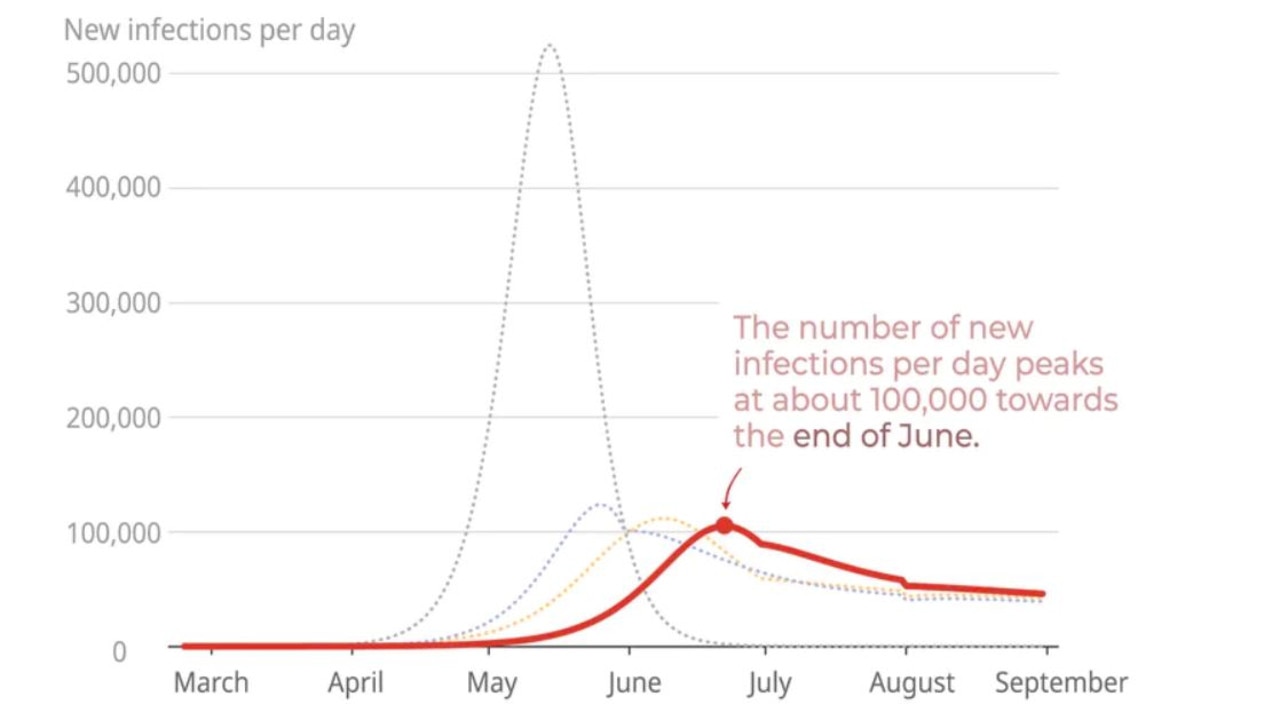

Prof Blakely has modelled various scenarios for flattening the curve and the consequences of acting more quickly or more slowly.

If flattening the curve is the tactic Australia is aiming for, then Prof Blakely says governments have acted too early in closing down businesses because there is still capacity in our health services, and restrictions could run for two months longer than necessary.

“We are not close to maxing out our health services and so have acted too soon,” he said.

“We are acting two weeks too early.”

RELATED: Coronavirus cases surge in NSW and Queensland

RELATED: Why we have to keep schools open for ‘herd immunity’

THE FORK IN THE ROAD

There are other reasons why authorities may be choosing to go hard now, even if they still intend to flatten the curve.

Prof Blakely said there could be concerns that health services were not ready yet for peak loads within six weeks.

“That would be justification for acting harder now, to buy more time and get services up to speed,” he said.

The other justification could be that doctors may be able to work out better ways to save lives if given more time.

Prof Blakely said there was already some promising evidence that giving patients old retroviral drugs, generally prescribed to treat HIV AIDS, before they became critically ill may be helping.

Another option to reduce the impact of coronavirus would be to reduce the infection rate among the elderly by protecting them as a priority. If the infection rate among older Australians could be reduced from 60 per cent to 20 per cent then this would halve the number of deaths.

Combined with better treatments, this could bring the number of predicted deaths in Australia down from 130,000 to 30,000.

“That’s not bad when you consider about 19,000 a year die from tobacco-related causes in Australia,” Prof Blakely said.

He acknowledged that authorities were faced with a careful balancing act but said they needed to be clearer with the public about their strategy.

“The thing at the moment, is we need our Prime Minister and our state premiers to actually agree on what that strategy is and to communicate it to the public,” he said.

“If we go into physical lockdown in two to four weeks time, the public might get sick of it when they realise they have another 10 weeks to go, and we’ve gone early.”

“We have 48 hours to reach a consensus and to tell the public what that goal is. Then we need to look at the policies that have been put in place and whether they will achieve those goals.”