Which is the worst Australian takeover mistake of the century so far?

Writing off the entire value of assets you’ve just spent $1.25bn buying is never a good look. But how does IGO’s disastrous takeover compare to the worst ever?

Business

Don't miss out on the headlines from Business. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Writing off the entire value of assets you’ve just spent $1.25bn buying is never a good look. But how does IGO’s disastrous takeover compare to the worst of this century’s terrible takeover decisions in Australia?

The decision of IGO to wipe off almost the entire value of Western Areas’ assets only a year after spending $1.25bn cash on buying the WA nickel play surely ranks as one of the worst takeover mistakes – for the speed of the decision, if not its total cost.

South32’s recent decision to write off $US1.3bn from the value of its Hermosa project in the US – bought in a deal valuing owner Arizona Mining at $US1.6bn in 2018 – is another recent candidate for the list.

But how do you judge the scale of a takeover disaster?

The simplest method would be to rank the total impairment and writedown, and use that as a measure of the destruction of shareholder value.

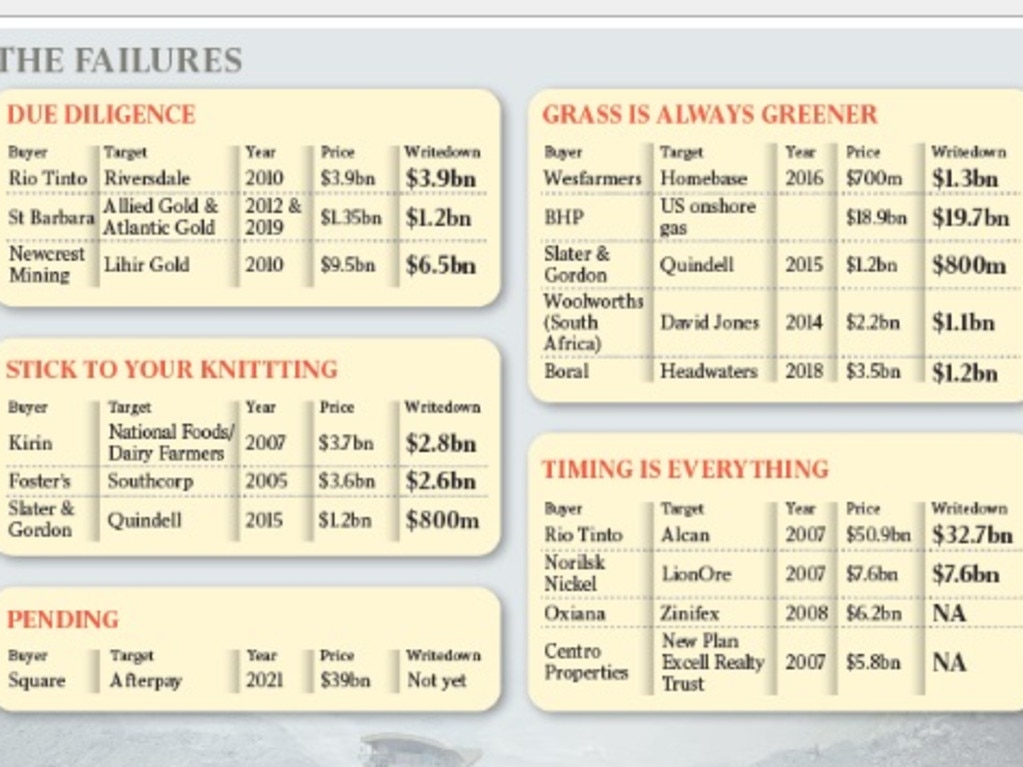

In that case, Rio Tinto’s $32.7bn drubbing on Alcan under Tom Albanese’s leadership would surely top the scales.

The size of the acquisition, and subsequent impairments, is eye-watering even now. But the bulk of the Canadian aluminium assets acquired still remain a profitable part of Rio’s global portfolio – and there’s a pretty good argument to suggest the Alcan acquisition also acted as the biggest poison pill in corporate history, helping fend off a hostile move by BHP on its rival (although regulators would surely have put paid to that anyway).

Does that make the disaster better or worse than BHP’s $19.7bn in write-offs on its US onshore gas foray? The need to pump more capital into the assets meant BHP wrote off more than it spent buying the projects and, while BHP Australia boss Geraldine Slattery – who worked in Houston as the gas price dived – says the resources giant learned a lot from the experience, it was an expensive lesson by any standards.

But there are acquisition disasters that, while not losing as much cash as those standout examples, arguably inflict more damage on the buyer than just book value.

A slew of failed offshore acquisitions suggest that, despite the view from afar, the grass is not always greener on the other side of the oceans. Boral’s US foray through its $3.5bn acquisition of Headwaters under CEO Mike Kane led to only about $1.2bn in writedowns – but acted as a millstone around the company’s neck for years, and effectively opened the gate for Kerry and Ryan Stokes’ Seven Group to win control of the company.

Wesfarmer’s attempt to replicate the success of Bunnings in Britain both consumed more cash than the initial acquisition value, and distracted management for years before the WA conglomerate – like Boral – performed a humiliating about-face and abandoned the strategy.

That theory also works in reverse, of course, as witnessed by the substantial losses faced by the South African company Woolworths, which lost about half of the $2.2bn it spent buying David Jones in 2014 before finally giving up and flogging the department store chain to Anchorage Capital for $120m in late 2022.

Then there are those failures that blow up the parent company, such as listed law company Slater & Gordon’s $1.2bn acquisition of British firm Quindell, which went south within months amid regulatory investigations of dodgy accounting at the UK company.

Slater & Gordon’s stock plunged, its debt was bought by hedge funds, and the firm eventually limped off the ASX this year after a private equity buyout.

The Quindell disaster is probably the greatest failure of due diligence in recent Australian corporate history – and certainly the most incomprehensible, given Slater bought the company after a damning short-selling report had already aired most of the claims that eventually brought the takeover undone.

But it’s hardly the only entry in what is a key terrible takeover category. Rio lost $3.9bn buying Riversdale Mining on the assumption it could barge up to 45 million tonnes of hard coking coal down the Zambezi River in Mozambique – while somehow ignoring internal and external warnings that the barging option would never be allowed.

And St Barbara makes the list on the regularity of its failures, if not necessarily their size. Its $484m cash and scrip acquisition of Allied Gold in 2012 somehow failed to spot the problems at its target’s PNG and Solomon Islands gold mines, and the buyout nearly buried the company in debt. Only the rising gold price and sweating the company’s Gwalia mine in WA got the company through.

And then St Barbara’s new board and management repeated the feat, splashing $780m to buy Canadian miner Atlantic Gold on the incorrect assumption it could easily turn resources and reserves into tonnes through the mill. This time Gwalia couldn’t save the company, and St Barbara was forced into asset sales, leaving it with only the legacy of the two failed buyouts – and not its former crown jewel.

St Barbara is, of course, the corporate heir to legendary WA gold company Sons of Gwalia, which collapsed under the weight of a toxic hedge book in 2004 – partly as a result of another troubled acquisition setting the company on the road to ruin.

Failed attempts to diversify are also a common hallmark of the truly disastrous acquisitions – even worse when combined with a move offshore.

Headlined by its $3.5bn acquisition of Southcorp in 2005, Foster’s spent billions trying to prove that selling beer was much the same as selling wine. Turns out it’s not. Japan’s Kirin thought that selling dairy products was the same as selling beer, and spent $3.7bn on National Foods and Farmers. That turned out pretty much the same way as the Foster’s experiment.

And, on the propensity of Japanese giants to waste money, who can forget Japan Post’s bizarre decision to blow up billions on buying out Toll Holdings in 2015?

And then there’s the classic top-of-the-market buyout, rapidly followed by a crash.

The extraordinary volatility of commodity markets makes resources companies the standouts in the field, but they are not alone.

After a frenzied bidding war with Xstrata, Norilsk Nickel stumped up $7.6bn to buy WA nickel producer LionOre in 2007. The nickel price turned immediately, and the mines it bought were shut within a year or so of the deal closing. Xstrata’s $3.1bn acquisition of its other target, Kerry Harmanis’ Jubilee Mines, didn’t turn out much better.

Similarly, Oxiana’s $6.2bn takeover of Zinifex in 2008 – which created OZ Minerals – was in trouble within months, and the commodity crash sparked by the Global Financial Crisis forced the company to sell most of its assets to China’s Minmetals.

But it’s not just the miners that fall victim to sudden changes of fortune on the market. Centro Properties managed much the same feat when it spent $5.8bn on New Plan Excell Property Trust right on the eve of the GFC.

And then there’s the monster still to come. Jack Dorsey’s Square paid $39bn for Australian buy now, pay later company Afterpay in one of the biggest deals the ASX has ever seen.

But, with rates rising and spending tightening, many expect the writedowns on this megadeal to be just as big.

More Coverage

Originally published as Which is the worst Australian takeover mistake of the century so far?