The worrying warning sign behind Jim Chalmers’ mid-year budget update

The commodity super-cycle is rapidly coming to an end, and Australia’s finances are nowhere near ready for this moment.

Business

Don't miss out on the headlines from Business. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Behind Jim Chalmers’ mid-year budget update is a warning Australia’s multi-decade mining super-cycle is starting to fade. And with it are the boomtime revenues which flow directly to Canberra to prop up the budget.

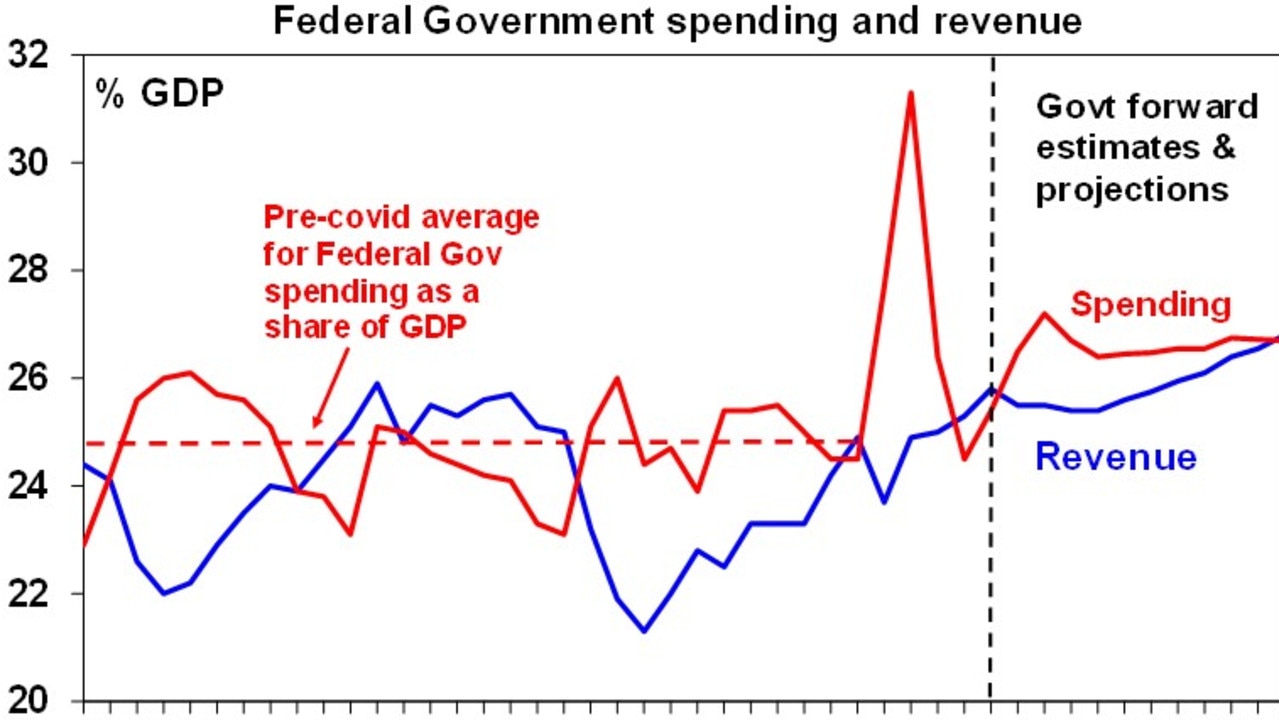

What isn’t going away however, are the structural pressures forcing up spending, triggering a $21.8bn budget deficit blowout over coming years and ballooning debt. Indeed spending is now expected to increase $42.2bn over the forecast period, with total spending as a share of GDP well up on pre-pandemic levels. This isn’t matched with like for like savings.

With limited appetite for reform on both sides of politics, this sets Australia up for recurring deficits right through to the end of the decade. Indeed, a miracle turnaround in the government’s balance sheet on the revenue side will be needed to get the budget back in the black well into the 2030s.

For the first time since the Covid pandemic, company tax receipts have been revised down by $6.6bn for next financial year and by $8.5bn over the four year outlook period. The 4.7 per cent drop this year is largely due to lower mining profits as well as falling oil prices impacting LNG exports.

While the drop can largely be sheeted back to the shaky ground the Chinese economy now finds itself on given the bursting housing bubble and poor consumer confidence, this is a taste of things to come.

Australia needs to prepare for the moment of China hitting “peak steel”, when it no longer needs to buy ever-increasing volumes of Pilbara iron ore — and we are far from ready for this.

For years the mining bubble has supported ever increasing levels of government spending and national wealth. Now, the structural pressures on the budget are only getting bigger while the corporate tax take falls away.

These forces are all laid out in the mid-year update, with ageing population, higher defence spending, rising demand for healthcare services as well as the sting of interest payments on government debt all driving up spending in the budget. One of the fastest-growing demands on the budget is the National Disability Insurance Scheme and aged care services.

This year spending is forecast to lift by 5.7 per cent, further adding to inflation pressures in the economy, and this follows a near 3 per cent rise last year.

The increasing spending demands mean there is little prospect for meaningful tax reform businesses have long been calling for.

As Soul Patts chief executive Todd Barlow told The Australian’s CEO Survey: “Australia is spending at record levels, and we really need to see lower expenditure and lower employment growth from the government to reduce interest rates”.

Gross debt, which net interest payments are calculated on, is forecast to balloon to $1.1 trillion by 2028 as deficits continue to widen. This debt is up from $940bn currently — slightly higher than the $934bn forecast in the May budget.

Chalmers says his previous budgets had delayed — but haven’t been able to stop — breaching the $1 trillion mark in a few years. Even so, the delay has helped avoid an “absolute mountain” of interest in the meantime, he told reporters.

Australia’s terms of trade, or the ratio of export to import prices, are forecast to decline by 5.25 per cent in 2025, the update says. Iron ore prices have been under pressure since the start of 2024 and remain under pressure from slowing growth in China.

Treasury assumes China’s growth will start slowing in each of the next three years, including falling short of Beijing’s own 5 per cent target this year. This will mark the weakest consecutive three-year period of growth since China opened up to the global economy in the 1970s. With China underperforming that sets Australia up for a difficult three years.

Mining giant BHP’s own long-range iron ore forecasts assume China’s steel production will plateau at about 1 billion tonnes around the mid-2020s.

Beyond that, demand for raw ingredients in steelmaking including iron ore will face competition from more scrap steel, BHP has said. This will be not only underpinned by high scrap availability but also from policy mandates pushing for lower energy consumption and carbon emissions in the steel sector.

The mid-year update is still tipping iron ore prices to average $US60 a tonne by September, this is unchanged from the May Budget. Treasury has long undershot iron ore price estimates with the metal trading at around $US105 a tonne.

A big uncertainty in the outlook for the global economy remains the incoming Trump administration’s promised tariffs, tax cuts and deregulation. These policies are “yet to be settled”, the mid-year budget papers say.

Despite the alarming reversal in the company tax take and subdued outlook for productivity growth, Treasury has assumed business investment will increase at a faster rate in the coming year. It comes as the GDP outlook has been trimmed for the current year.

If Treasury gets these critical assumptions wrong it’s likely to be a big miss for its growth forecasts.

Treasury assumes non-mining investment will increase by 2.5 per cent in the current financial year, and by a further 2 per cent a year later, sitting at decade highs. Much of this investment is on the back of government-funded infrastructure investment with the states leading the spending charge, it says.

Earlier Wednesday, National Australia Bank chief executive Andrew Irvine told shareholders he was expecting the Reserve Bank to start cutting the cash rate in the first half of 2025 with pressure on inflation easing. Irvine said from his vantage point, the economy was in “reasonable shape”, although business and households were feeling the pressure of inflation.

Chalmers says in order to get the budget in better shape, you must have spending restraint and argues the $92bn in savings since taking office “is not minor”.

So too the structural pressures “are not being ignored” with discipline being pointed around spending in NDIS, aged care and interest costs.

With the company tax boom coming to an end, this spending restraint may not come fast enough.

Share strike

ANZ has become the latest bank to be hit with a shareholder strike after a horror end to the year as it remains under investigation over its bond trading business and has been put on a tighter leash by the banking regulator.

A more than 25 per cent vote against the bank’s remuneration report at the AGM delivers a strike, with Westpac the last of the big four banks to cop a protest vote in 2021. National Australia Bank famously scored an 88 per cent protest vote after top executives and board were singled out for criticism following the Hayne banking royal commission.

Proxy flows ahead of ANZ’s annual meeting scheduled for Thursday show a “no” vote building against the bank, with the charge being led by several big offshore funds, including Californian fund CalSTRS. Proxy numbers released by the bank on Thursday show a 38.3 per cent no vote. The bank too was also forced to pull a plan asking shareholders to support a performance right issue to Shayne Elliott, after a whopping 50 per cent of investors voted against it.

With the strike vote below 40 per cent, ANZ clearly has some support among local fund managers, but not everyone is impressed with the year just passed which also saw the bedding down of the Suncorp acquisition.

In August, bank regulator APRA forced the Paul O’Sullivan-chaired ANZ to set aside even more funds on its balance sheet to cover perceived and actual risks. This so-called cash penalty it needs to hold is now sitting at $750m. This is not far behind the $1bn charge Westpac and Commonwealth Bank were forced to carry around at the worst of their respective clashes with Austrac. CBA has since been able to drop its $1bn charge, while Westpac has since had its penalty knocked down to $500m.

Chief executive Shayne Elliott has also seen as much as $1m docked from his pay this year as a result of the cultural problem in the markets business. ANZ has sacked several traders in its bond team after some allegedly had come back drunk from long lunches and other troubling behaviour. At the same time an internal investigation has uncovered some double counting on bond entries.

And this week The Australian revealed the bank is being probed for charging fees on deceased estates – the very thing that got AMP into hot water during the banking royal commission.

Even when banks are going well, investors have little margin for error. National Australia Bank just saw through a textbook leadership transition to new chief executive Andrew Irvine. Even with shares up more than 25 per cent this year and no negative surprises, NAB copped a higher than expected 5 per cent protest vote at its annual meeting on Wednesday. This followed 3.9 per cent at the Westpac annual meeting and less than 2.5 per cent for CBA in recent months.

The meeting comes as ANZ this month outlined the retirement of Elliott by the middle of next year, with former HSBC and Santander executive Nuno Matos to take over. Matos is under a non-compete rule after he left his role as head of wealth and personal banking at HSBC in November. This week, ANZ warned a potential protest was being planned to disrupt the meeting and as a result has been forced to beef up security.

eric.johnston@news.com.au

Originally published as The worrying warning sign behind Jim Chalmers’ mid-year budget update