MYEFO shows $58.3bn surge in government spending and $26.9bn budget deficit

The mid-year economic and fiscal outlook shows an improvement in the 2024-25 budget bottom line will give way to deficits totalling $143.9bn to 2027-28 — $22bn more than initially projected.

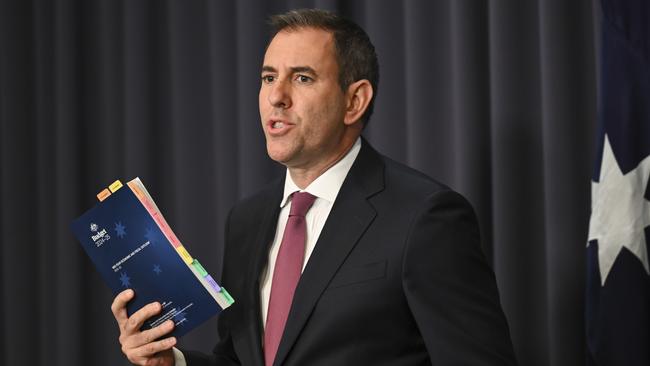

Jim Chalmers’ $58.3bn pre-election splurge in the mid-year budget update has projected a decade of deficits and a four-year $22bn blowout to the bottom line, sparking business fears that Labor’s record spending is prolonging the cost-of-living crisis and delaying rate cuts.

The mid-year economic and fiscal outlook released on Wednesday revealed a 5.7 per cent surge in real spending growth, the largest annual increase outside a recession or major financial crisis since the mid-1980s.

Ahead of next year’s federal election, the MYEFO showed the budget would plunge deeper into the red over the next four years, with Treasury forecasting consecutive budget deficits amounting to $143.9bn over the forward estimates.

The Treasurer’s budget update, which included a secret $5.6bn election war chest and $21.5bn of new spending characterised as “unavoidable and automatic”, sets up Anthony Albanese for an early run at the polls if he skips the March 25 budget.

Despite pressure on the government to rein in expenditure, federal spending as a share of GDP is expected to rise to 27.2 per cent next financial year, a level not surpassed in 39 years excluding two pandemic years under the Morrison government.

The headline cash balance – which incorporates “off-budget” spending including Labor’s $16bn cut to student debts and its Future Made in Australia investment vehicle – is expected to record a $47.8bn deficit this financial year, deepening to $70.3bn in 2025-26.

Amid weak domestic economic conditions, Treasury has downgraded economic and wages growth in 2024-25 to 1.75 per cent and 3 per cent respectively.

While trimming net debt forecasts over two years, the MYEFO projected higher debt levels in following years. Gross debt levels are now on track to hit $1.16 trillion by 2027-28.

The MYEFO also revealed a blowout in migration forecasts since the May budget, with net overseas migration levels increasing from 260,000 to 340,000 in 2024-25.

Business leaders warned on Wednesday that higher government spending was “destroying the bottom line”, prolonging the cost-of-living crisis and keeping interest rates higher for longer.

The Business Council of Australia, Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry and Australian Industry Group said the higher spending, debt and deficits “paint a worrying picture”.

Dr Chalmers, who spruiked a $26.9bn deficit in 2024-25 after lowering May forecasts by $1.3bn, defended the government’s higher expenditure and attacked critics who said there was “too much spending”.

“The reason we use the real spending figure is because it takes into consideration a whole bunch of things which are unavoidable, including indexation,” Dr Chalmers said.

“One of the big drivers of the extra spending in the budget update … is indexation of things like the age pension, working age payments and the like. So that explains a big part of the spending which is there. But compared to the levels of spending that we inherited a couple of years ago, we’re making decent progress.”

Opposition Treasury spokesman Angus Taylor, who is yet to release the Coalition’s economic plan to lower government spending, said federal Labor was now the “biggest spending government outside of wartime or a global crisis”.

“At a time when inflation is still too high, Jim Chalmers and Anthony Albanese have added an additional $347bn in spending since the election,” Mr Taylor said.

“Labor is spending $12 for every $1 saved, just in this budget update. The only thing Jim Chalmers does more than spin is spend. If Labor gets another term, migration will hit 2 million in total with no plan for housing and infrastructure.”

Dr Chalmers, who delivered surpluses of $15.8bn in 2023-24 and $22.1bn in 2022-23 off the back of post-pandemic migration and labour and mining booms, said that “despite all of the pressures in our budget, we are on track for a soft landing in our economy”.

“You can see that right across the economic indicators that we are talking about today,” the Treasurer said. “The economy is growing, but slowly. Inflation is moderating. Real wages and real incomes are growing. Unemployment is low. A million jobs have been created. We need to remember in the international context that most of the OECD has had a negative quarter of growth. We have escaped a negative quarter of growth to date. Our budget improvement since 2021 has been much faster than the average of advanced economies and the specific comparison with the economies that we usually refer to.”

BCA chief executive Bran Black warned that Labor’s increased government spending, not linked to productivity gains, would “make it harder to bring down inflation and ease cost-of-living pressures”.

“We’re concerned about the impact of increased government spending and the distortion that creates across our economy for investment, skills and our workforce,” Mr Black said.

AiGroup chief executive Innes Willox said the government’s spending-to-GDP ratio was at its highest level since the mid-1980s. “The only forecast indicator to be materially upgraded is government spending, which will grow by 5.7 per cent in real terms this financial year,” Mr Willox said. “The inexorable increase in government spending on public servants and social programs is destroying the national bottom line. The rising spending is also putting pressure on inflation and interest rates.”

Revenue generated from tobacco excise were revised sharply lower, down by $2.8bn in 2024-25 and $10.7bn over four years. Petroleum resource rent tax receipts were downgraded by $2bn.

Economist Chris Richardson said “our gas taxes are woefully inadequate” and warned of an “enormous gap between how we tax and how we enforce” the tobacco tax.

“To date they (the government) have made decisions that have raised spending by $124bn, and have raised taxes by $46bn, for a net worsening in the budget position across the forward estimates of $78bn,” Mr Richardson said.

ACCI chief executive Andrew McKellar accused the government of shifting spending to reduce the deficit by $1.4bn in 2024-25, only to blow out deficits in coming years.

“The public sector continues to surge, with expectations for growth in public final demand increasing from 1.5 per cent in the budget to 3.75 per cent in MYEFO. However, activity in the private sector is forecast to fall from 1.75 per cent to 1 per cent, impeded by an increasing regulatory impost,” Mr McKellar said.

Projected changes to the budget bottom line will impact government borrowing. Net debt is expected to be reduced by $18.7bn across the first two years of the forward estimates compared with May, and climbing to $609.3bn or 21.3 per cent of GDP by 2025-26.

But from mid-2026, net debt is forecast to push higher than previously expected, blowing out to $708.7bn by 2027-28, or 22.4 per cent of GDP – higher than the 21.9 per cent figure projected in the budget earlier this year.

Despite company tax receipts being downgraded by $6.6bn in 2024-25 and $8.5bn over four years, overall tax receipts are projected to be $7.3bn higher than forecast in May. The bigger tax take is due to higher-than-expected personal income tax receipts, which are up $21.5bn over the forward estimates.

The tax-to-GDP ratio – which measures total tax revenue as a share of the economy – is forecast to be 23.4 per cent for the current financial year, up from the 23.3 per cent projected in May but still short of the 23.9 per cent recorded during the Howard government.

Of the $7.3bn improvement in tax receipts, the Treasurer has returned 78 per cent or $5.7bn to the bottom line, short of the 96 per cent return rate in his 2023-24 federal budget.

The mid-year budget update also shows a projected $58.3bn increase in payments this financial year, up 5.7 per cent, which Dr Chalmers has sought to claim as both “unavoidable and automatic” in a bid to fend off criticism he is stoking inflation.

Since May, the government has outlaid $19.1bn for new spending decisions, while saving just $1.7bn, amounting to new net spending worth $17.5bn. At the same time, parameter variations – reflecting indexation of government payments and pensions alongside extra funding to cover greater than expected demand in services – have surged by an additional $23bn on May’s projections.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout