Inflation explained: Why Aussie households are in for more pain

Australians have dealt with spikes in inflation before, but there’s a worrying detail that could make the coming months even more difficult than we’ve seen before.

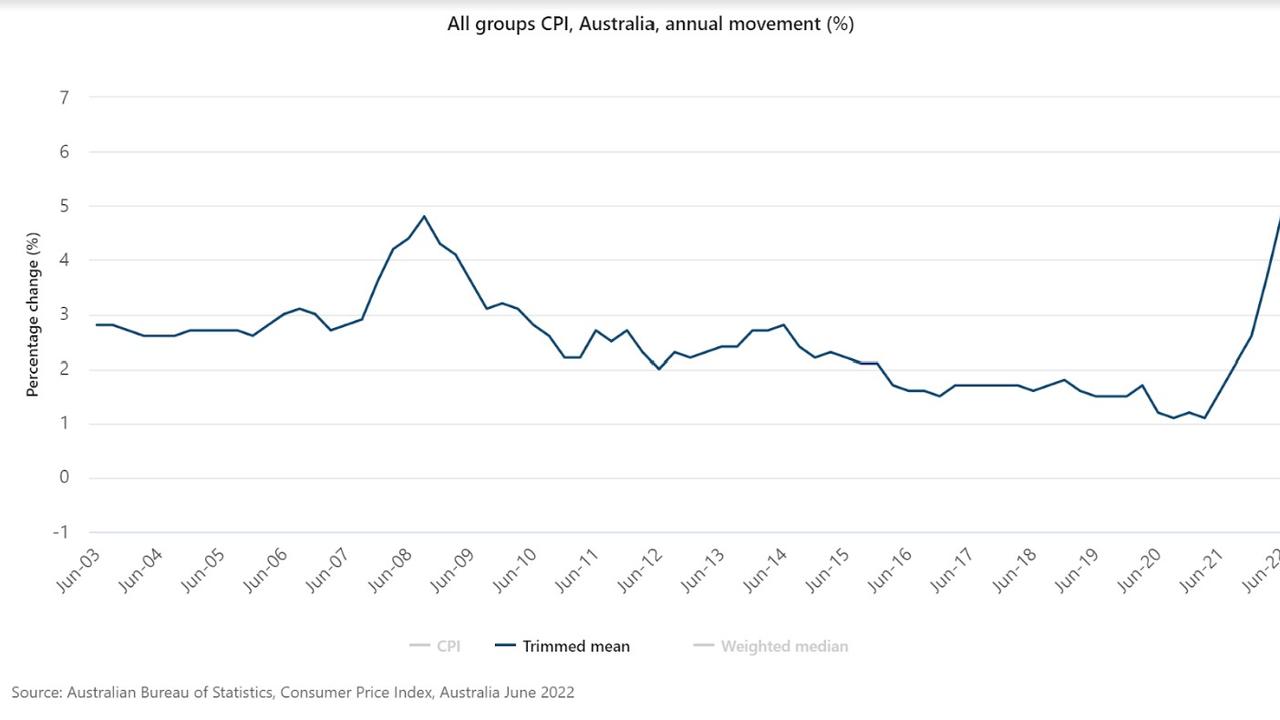

Over the last 12 months Australians have been given quite an education on inflation, with the headline CPI recently hitting 6.1 per cent.

After over a decade of inflation lying largely dormant in relative terms, the recent cost of living pressures largely blindsided households and even the experts at places like the Reserve Bank (RBA).

As inflationary pressures continue to build within the economy, Treasury and the RBA both predict that the worst is not yet upon us and will come later in the year, with headline inflation expected to hit 7.75 per cent.

But not all inflation is created equal and some inflationary forces are considered far worse than others.

The central bank perspective on inflation

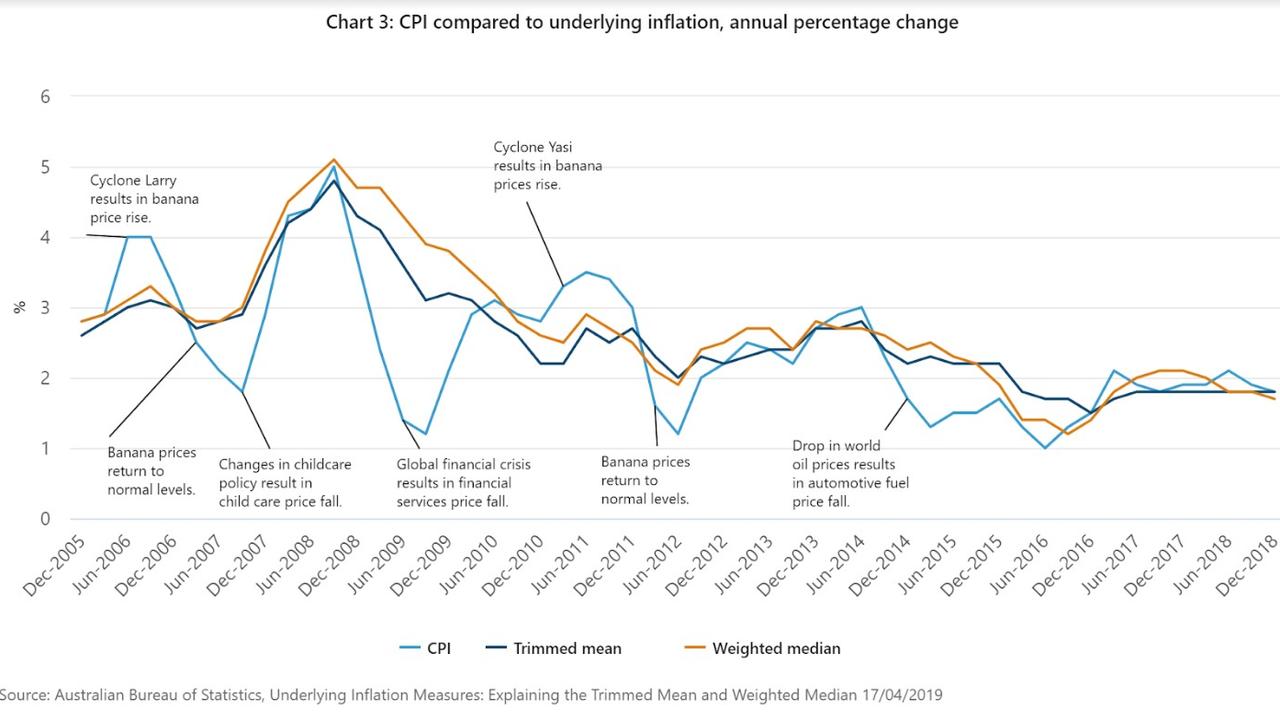

For example, petrol and food prices can be extremely volatile. At times, the cost of fresh produce can rocket for months at a time due to natural disasters or drought, before returning to roughly where it was before the price spike began.

In some past instances it’s been a similar story for fuel prices. A geopolitical event or a natural disaster impacts oil prices and in short order we are all paying more for fuel at the pump. But as the impact of these events fade, prices in some instances have returned to broadly where they were prior.

For this reason central banks around the world including Australia’s own RBA prefer measures of inflation that remove or attempt to iron out these volatile moves in consumer prices. In Australia, the metric used is called the “trimmed mean”, which is put together using a weighted average of the middle 70 per cent of the basket of goods and services used to calculate the consumer price index.

For example, after banana and other fresh produce prices rocketed following the impact of Cyclone Larry in 2006, headline inflation jumped from 2.9 per cent to 4.0 per cent in just three months. Meanwhile, the trimmed mean metric recorded just a 0.2 per cent increase to 3.0 per cent during that time.

On the other side of the coin, during the Global Financial Crisis, the collapse in the cost of financial services and other products resulted in the headline CPI dropping from 5.0 per cent in the September quarter of 2008, to just 1.2 per cent in the September quarter of 2009.

Once again the trimmed mean metric showed that broader inflationary pressures outside of the more volatile items reduced by significantly less across the same time period, dropping from 4.8 per cent to 3.1 per cent.

The Global Financial Crisis experience and how it compares

Last time inflation was anywhere near this high was just prior to the Global Financial Crisis. In both Australia and the United States inflation peaked just before the collapse of investment bank Lehmann Brothers sent the global financial system into meltdown.

Perhaps unsurprisingly the worst financial and economic crisis since the Great Depression sent headline inflation packing in short order. In five months headline US inflation dropped from the highest level since 1991, to just 0.1 per cent.

However, things are quite different now when contrasted with 2008, both in Australia and in the United States.

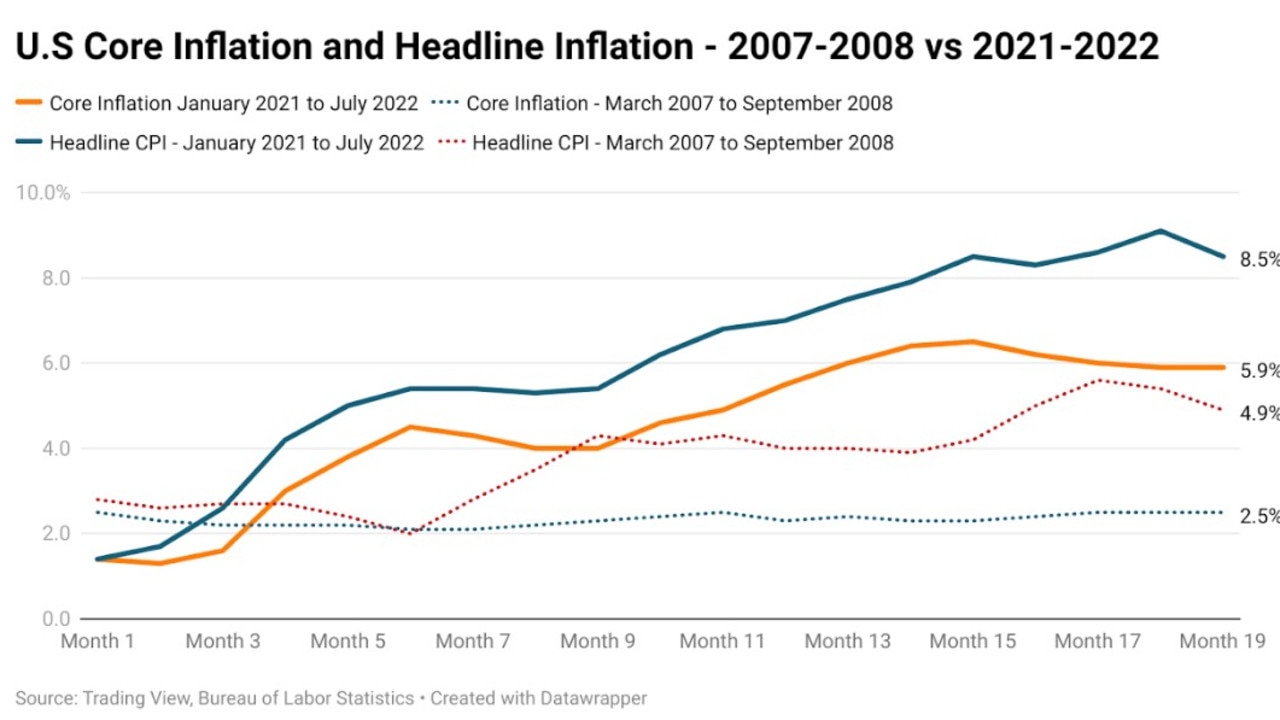

For a start, in the present day, Australian and American headline inflation are set to peak significantly higher than in 2008, 7.75 per cent versus 5 per cent in 2008 for Australia and 9.1 per cent versus 5.6 per cent in the US.

This brings us back to the central banks’ preferred metrics of measuring inflation — in Australia’s case the trimmed mean and in the US Core CPI. In the United States, the current rate of core inflation (which strips out the impact of food and energy costs) is 5.9 per cent, compared with a peak of just 2.5 per cent in 2008.

In short, in 2008 inflation was driven extremely heavily by food and energy, while in 2022 they are both significant factors, but inflationary pressures are far more broad based.

In Australia, the RBA’s preferred inflation metric is already sitting at its highest level (4.9 per cent) since the early 1990s and is set to go significantly higher as inflation heads for its expected peak of 7.75 per cent in the December quarter.

With inflation now entrenched across much of the economy, it could take quite some time for the RBA’s actions and a slowing economy to tame the cost of living pressures being felt by households.

Why this all this matters

Bar some manner of repeat of the Global Financial Crisis or something similar, inflation is likely to continue to be an issue for quite some time.

This is the challenge central banks around the world are considering extremely carefully. In Britain, the Bank of England has resolved itself to continue to raise interest rates aggressively, while at the same time acknowledging that the UK economy is in for a long hard recession.

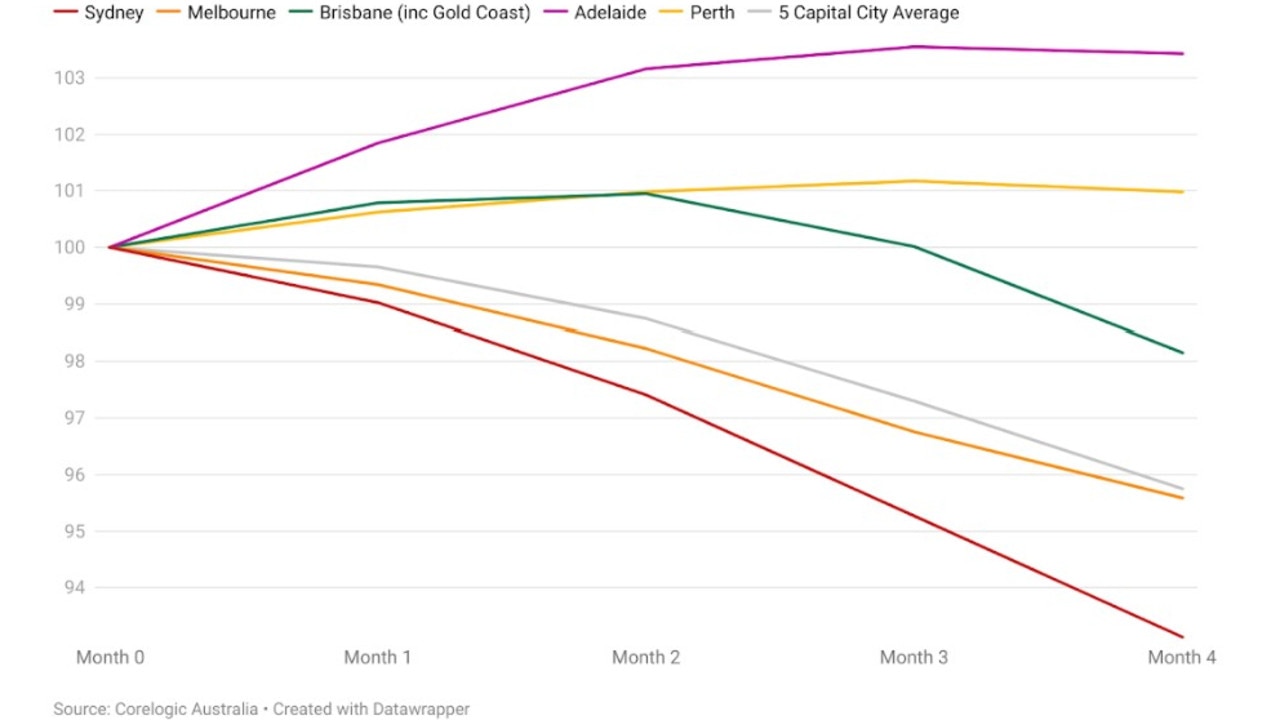

How the RBA ultimately decides to approach this challenge could decide the fortunes of millions of Australian mortgage holders and property owners. If they follow the path blazed by the Bank of England, Australians could see rates rise even as the global economy deteriorates significantly and higher rates begins to put pressure on the domestic economy.

With housing prices already falling rapidly in Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane, and the other capitals now also weakening, the RBA’s approach could be the defining factor of at least the short term future of the property market.

But as US Federal Reserve Jerome Powell recently pointed out, from the perspective of central banks, the pain from the loss of “price stability” aka the result of high inflation, is far worse than falling asset prices or rising interest rates.

On the other hand, they may choose a different path and decide that it doesn’t have the stomach to raise rates into a slowdown. But that too may have consequences. In the early 1970s an insufficient commitment to fight inflation from central banks, most notably the US Federal Reserve, helped to entrench inflation for years to come.

Headline CPI inflation will always be the metric that grabs people’s attention and leads the nightly news, but it is the core underlying inflationary pressures that will ultimately help to decide central bank policy and mortgage rates.

Tarric Brooker is a freelance journalist and social commentator | @AvidCommentator

Originally published as Inflation explained: Why Aussie households are in for more pain