‘Can’t spend $7 on a donut’: Rising cost-of-living takes a bite out of hipster ‘fad’

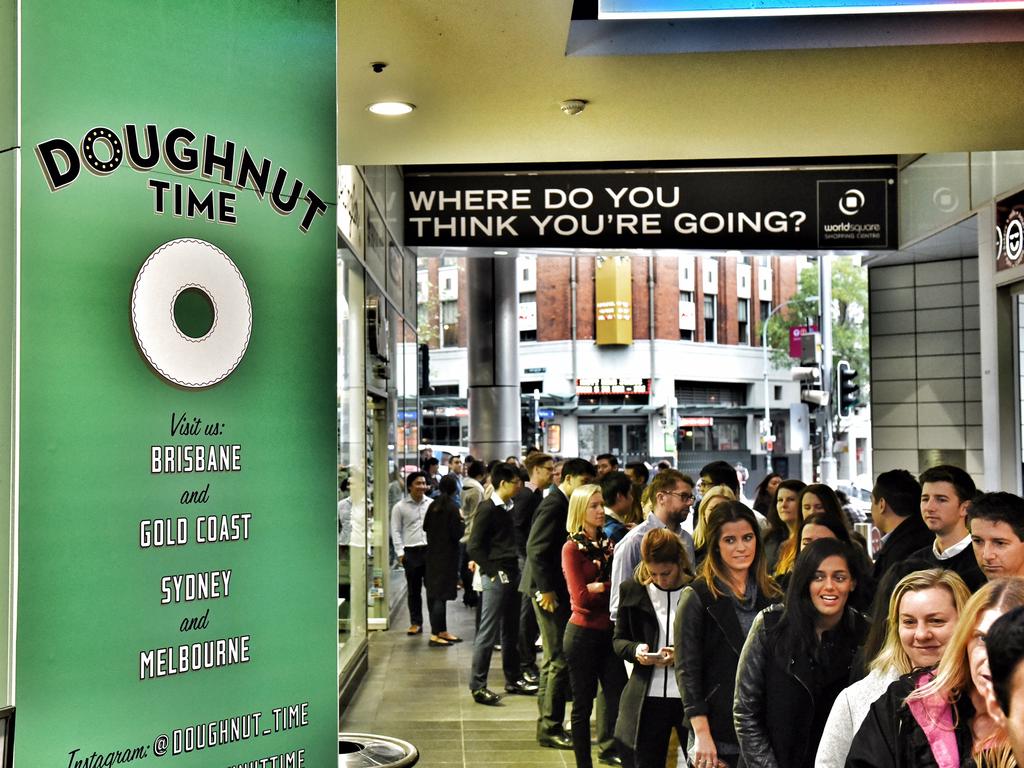

Less than a decade ago, Aussies stood for hours in snaking queues in a bid to buy a product from this cult store. Now, the entire industry is on life support.

Retail

Don't miss out on the headlines from Retail. Followed categories will be added to My News.

EXCLUSIVE

There are no dollars for donuts these days — or at least far fewer, as Aussies shun the once-popular hipster dessert amid rising inflation and health-consciousness.

The gourmet donut space, which saw a massive boom around half a dozen years ago as the extravagantly decorated treats took over Instagram feeds, has seen a raft of closures and consolidation in recent months with brands forced to shift business models to survive.

Gone are long lines outside hole-in-the-wall donut stores — now the real dough is found in big-ticket wholesale tie-ups with supermarkets, servos and even corporations looking to entice workers back into the office.

“You know how it is — the burger stuff went crazy, froyo went crazy — you’ve got five years,” said Peter Andros, the Gold Coast businessman who purchased Doughnut Time out of liquidation in 2018.

“Everyone jumps in, dilutes the market, the market contracts and only the big guys survive. We’ve all seen it with the froyo stores, they were so popular. Yo-Chi, they’re back, all hot at the moment. They’ve got five years. It’s only a matter of time before everyone opens a froyo store again, it’s the same flavour-of-the-month thing we see.”

Doughnut Time pioneered the Instagrammable donut trend in Australia, growing to 30 stores across Australia and the UK in a few short years before collapsing under a mountain of debt.

Its original founder, disgraced Queensland restaurateur Damian Griffiths, fled the country in 2019 still owing $30 million to suppliers and staff. Mr Griffiths last year re-emerged in Europe with new stores under the Doughnut Time brand — not affiliated with the Australian company — for which he retained the international rights.

The local business was rescued and rebuilt by Mr Andros, who struck a major deal with Ampol service stations.

But over the last six months, Doughnut Time closed its remaining two retail locations in Brisbane and the Gold Coast as the leases ran out.

“We’re focusing on our 570 Ampols,” Mr Andros said.

“There’s a lot of work that goes into your stores, you’re paying for staff wages, all these overheads. After Covid food costs went up about 30 per cent, then staff costs keep going up.”

But he said the stores themselves “didn’t see that much of a significant drop” in sales and he would have kept them open if not for the Ampol deal.

“It’s so easy to do corporate and so hard on a staff basis to do storefront,” he said. “For us it’s only making 5 per cent of our turnover — why am I doing 99 per cent of the work for 5 per cent? But I understand what these other guys are going through [that don’t have corporate deals].”

The industry was dealt a massive blow six months ago with the collapse of Melbourne’s Mr Donut, one of the oldest wholesalers in the space.

And earlier this month Donut Papi, a popular Filipino-inspired store in Sydney’s inner west, announced it was making the “very hard decision” to close down from July after nearly a decade.

“There seems to be a pattern … I think because of inflation, donuts are such a luxury food item and sales are very, very low at the moment, that’s what made me close,” said Donut Papi founder Kenneth Rodrigueza.

Mr Rodrigueza started the Donut Papi brand with his sister Karen nine years ago, initially selling at markets before opening their first store in Redfern, and then moving to a bigger location in Marrickville last year.

“I think we really felt it late last year,” said Mr Rodrigueza.

“Once we opened we were really busy, busier than what we’d imagined in that honeymoon period, but the fifth and sixth month it was really quiet. I know summer is our quietest period, I thought maybe it’s just because it’s summertime no one wants to eat sweets and desserts, but it’s June now, [usually] our busiest month and nothing’s happening.”

Mr Rodrigueza, who plans to turn the Marrickville location into a more “everyday” store offering Filipino-style merienda, or afternoon tea — bakery staples, sandwiches, rice dishes — conceded the era of the gourmet donut may have run its course.

“I’m really proud of what we did for Donut Papi,” he said.

“We lasted nine years with one product. We tried everything you can imagine — sweet, savoury, everything in between. Definitely though because we had one product, it’s a luxury, and there are a lot of other products and trends coming out, people are distracted.”

Mr Andros said the collapse of Mr Donut in particular was “a huge loss for the industry”.

Mr Donut’s supply contracts were acquired by Melbourne chain Daniel’s Donuts, which has more than 40 locations.

Daniel’s Donuts has been contacted for comment.

“I think it’s just the fad and the fad has, I would say, even changed a bit towards croissants and more pastries rather than donuts,” said Geoff Bannister, founder of Sydney’s Dr Dough Donuts.

Mr Bannister said while “we still sell a heap of donuts” the focus had turned much more to the gifting space and corporate sales, particularly from Tuesdays to Thursdays “as an incentive to get staff back into the office”.

“I’d say 50 per cent or so [of the industry woes] is due to the retail trends and I’d say the other side is possibly the health-conscious side,” he said.

“Particularly for us there was some big growth around 2018 when Doughnut Time had 20 or 30 sites. There was even growth through Covid. Covid was huge for us in regards to gifting because we were more an online retail play for gifting and corporates, so our average order value was a lot higher. I think that’s how we’ve withstood a lot of the economic impacts.”

The bread and cake retailing sector in Australia has estimated annual revenue of $973 million, according to IBISWorld, with growth of just 0.8 per cent over the past five years.

“Bread and cake retailers have faced a challenging trading environment in recent years,” the market research firm says.

“Fierce competition among industry retailers and from external sources like supermarkets has weighed on industry growth. Increasing competition has led to store closures for Retail Food Group (RFG), the industry’s largest player. Unlike many related retailing industries, the largest bread and cake retailers have not performed as strongly as their smaller counterparts. For example, RFG has closed many Donut King stores because of unsatisfactory lease agreements with shop landlords and declining shopping centre performance during the pandemic.”

Mr Andros predicted that the once the market settled, there would likely be only two or three big wholesale brands, with Krispy Kreme “going to be doing well”.

The iconic American franchise, which first came to Australia in 2003 before collapsing into voluntary administration in 2010, emerged with a leaner business and smaller footprint of physical stores, and soon signed a game-changing deal to sell donuts at 7-Eleven’s 600 convenience stores.

Krispy Kreme is now also sold in Coles and Woolworths.

“We’re just lucky we went into a different model [away from physical stores],” said Mr Andros. “We’re lucky we got in there.”

Mr Bannister said in addition to rising rents and labour costs, a big factor was the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) calling in unpaid debts from small businesses after the Covid-era reprieve.

“Anywhere between $100,000 and upwards towards $500,000,” he said.

“I’m hearing [about] people taking out a mortgage against their house to pay their ATO debt. I just look at that and go, if your business couldn’t afford to [keep running], why would you take that risk?”

Rising inflation and cost-of-living pressures have also put a hole in the pricey donut segment.

“If you’re paying $8 or $9 for a donut in these times, it may have gone from a once-a-week to a once-a-month,” Mr Bannister said.

Mr Andros agreed “people probably can’t spend $7 on a donut anymore, they’d rather walk out with $3.50”.

“Our servo stuff is doing really well, possibly because of inflation,” he said. “The servo donuts are a bit smaller and cheaper.”

He also said Doughnut Time’s corporate gifting was doing “very well”.

“Some people order 1000 donuts,” he said.

Originally published as ‘Can’t spend $7 on a donut’: Rising cost-of-living takes a bite out of hipster ‘fad’