China’s ‘completions cliff’ to send Australia spiralling

A crash looks imminent as a terrifying “completions cliff” looms which will change the face of Australia.

Mining

Don't miss out on the headlines from Mining. Followed categories will be added to My News.

ANALYSIS

Yes, it appears iron ore is going to collapse. The more pertinent question is when.

We need to examine the looming supply-and-demand equation to answer that question, which suggests huge swings are ahead.

Demand

Any iron ore analyst with runs on the board knows that the only market that matters is China which imports 70 per cent of it. More specifically, how much construction is happening within its economy?

Chinese property has crashed for two years. Prices are difficult to read, but they are down 5-20 per cent.

New apartment sales are down by about half since the peak.

Most importantly, new apartment starts by floor area, the projects actually being built, have crashed by 60 per cent annually.

At the peak, property was thought to comprise 40 per cent of Chinese steel demand, so why has steel demand not collapsed?

The main reason is that Chinese developers have a large inventory of half-finished dwellings. Building activity has yet to adjust to cratered sales and starts, but it will.

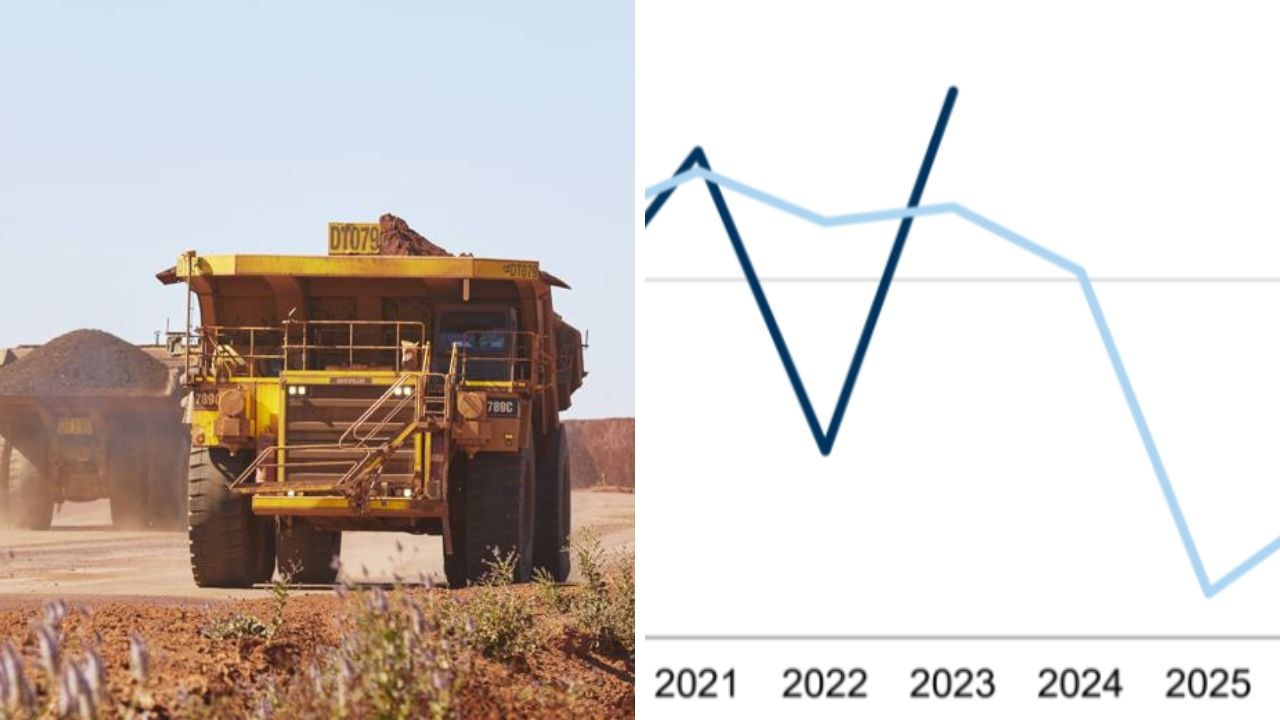

Goldman Sachs refers to this as the “completions cliff” and sees it coming in 2025:

In truth, it is already partially underway as many developers go out of business, but the big one is ahead.

There are some demand offsets in infrastructure and exports, but neither is big enough.

The “completions cliff” comprises 100 million tonnes (mt) or more of lost Chinese steel demand.

That is 160mt of iron ore, a little less than all of the output of Fortescue Metals Group.

Supply

Making matters considerably worse, major iron ore miners have lost their supply discipline at precisely the wrong moment.

Australian and Brazilian output will rise by 50-100mt over the next few years.

Then, in late 2025, RIO’s ill-conceived Simandou iron ore mine (colloquially known as the “Pilbara killer”) begins to flow.

Over the next few years, it will add another 60mt of iron ore supply to the seaborne market.

And, because it is partly owned and run by Chinese interests, it will damage the pricing power of the iron ore oligopolists in Australia and Brazil.

The crash

In summary, there will be an enormous swing towards surplus seaborne iron ore over the next few years.

The scale of the surplus is potentially even larger than that which transpired in 2014/15 when iron ore briefly reached $37 per tonne.

Worse, that crash was reversed when China massively juiced its property market for the last great hurrah.

This time, the drop in demand is structural and permanent, so the price will have to remain much lower for much longer to shutter many iron ore mines.

Where will they be? As in 2015, many iron ore juniors will disappear everywhere.

China will have to close many mines, which are expensive to run.

And the developing shake-out appears so severe that even the majors may be forced to rationalise output.

David Llewellyn-Smith is Chief Strategist at the MB Fund and MB Super. David is the founding publisher and editor of MacroBusiness and was the founding publisher and global economy editor of The Diplomat, the Asia Pacific’s leading geopolitics and economics portal. He is the co-author of The Great Crash of 2008 with Ross Garnaut and was the editor of the second Garnaut Climate Change Review.

Originally published as China’s ‘completions cliff’ to send Australia spiralling