Australia pumps up its push to establish a hydrogen industry

The world’s push to net zero by 2050 is providing incentive for Australia to put itself at the forefront of the hydrogen industry.

Business

Don't miss out on the headlines from Business. Followed categories will be added to My News.

A little more than two years ago, the nation’s hydrogen strategy was launched, drawing inspiration from Jules Verne – who predicted in 1874 that water, made up as it is of hydrogen and oxygen, would one day “furnish an inexhaustible source of heat and light, of an intensity of which coal is not capable’’.

Verne’s chemistry was on the money, but the fact that we don’t have a large-scale hydrogen fuels sector globally more than two centuries on points to the difficulties involved. They are problems that the world’s best minds, and importantly its investment capital, are now turning to with a keen focus, with the world’s push towards net zero by 2050 providing a huge incentive.

Australia’s strategy, launched in November 2019 by the then chief scientist Alan Finkel, envisaged the nation as a top-three exporter of hydrogen to Asian markets, with a “cautiously optimistic scenario” forecasting the creation of 7600 jobs and an extra $11bn in gross domestic product by 2050. While you could argue that industry and governments alike didn’t exactly race to pick up the hydrogen baton in the year following the release of the report, 2021 has been a different matter.

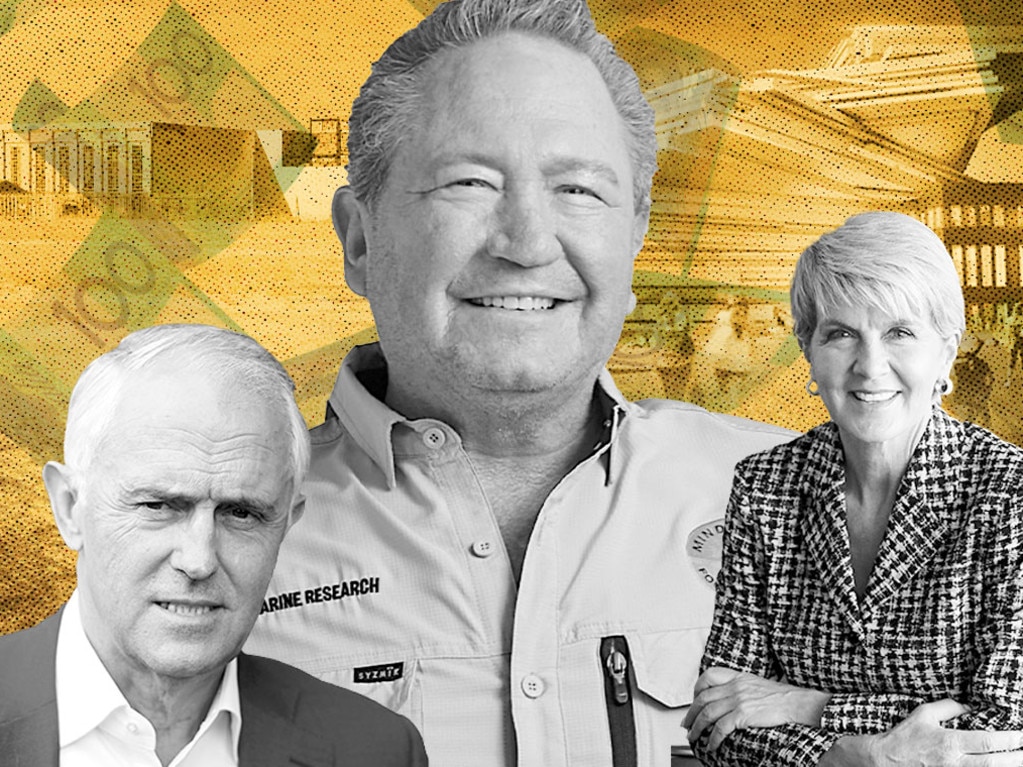

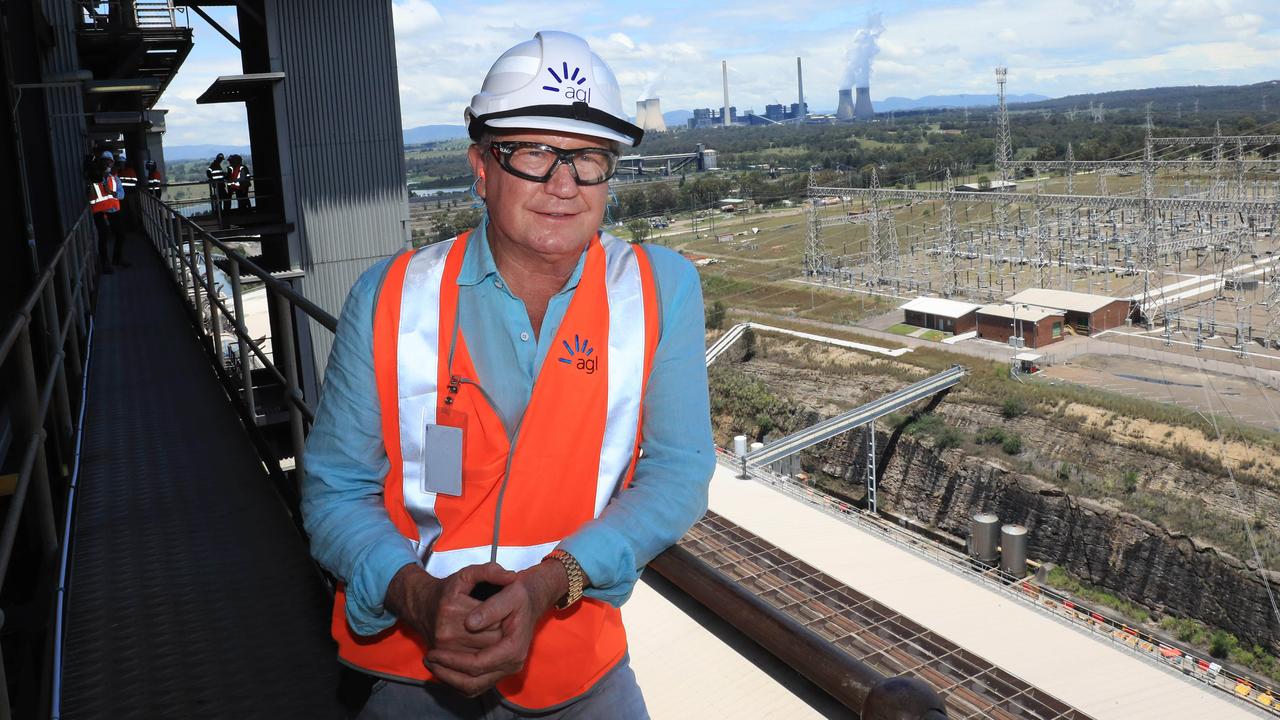

Iron ore magnate Andrew Forrest, through his Fortescue Future Industries, is targeting the production of 15 million tonnes of green hydrogen by 2030 – an ambition with a price tag in the hundreds of billions of dollars.

Santos has also shown its hand, with sign-off on its $US165m Moomba carbon capture and storage in Central Australia late last year opening the way for the production of so-called blue hydrogen, which involves stripping the carbon out of methane.

And Trafigura, one of the world’s largest commodities trading companies, has signed up for a $5m engineering study to assess the viability of a $750m hydrogen plant next to its lead smelter at Port Pirie. To put Forrest’s 15 million-tonne ambitions into perspective, the $750m Trafigura plant would aim to produce 36,500 tonnes of hydrogen a year from a 440 megawatt electrolyser – the kit used to crack water into hydrogen and oxygen.

While the federal government is yet to show its hand on exactly where the nation’s seven federally funded hydrogen hubs will be placed – expect more on that in the lead-up to the election – the detail is starting to be fleshed out, with Energy Minister Angus Taylor recently adding another $150m to the program.

There is now $464m committed to the program and seven favoured locations identified: Bell Bay in Tasmania, Darwin, South Australia’s Eyre Peninsula, Gladstone in Queensland, The Latrobe and Hunter valleys and the Pilbara in Western Australia.

Project consortiums can receive up to $3m to progress feasibility and design work, and up to $70m to roll out the projects themselves.

Manufacturing bid

As well as the plans afoot to crack water into its component parts, Forrest wants to build a billion-dollar-plus manufacturing facility in Queensland that will build the plant and equipment needed to make hydrogen, such as electrolysers, cabling and wind turbine components.

In the Northern Territory the Desert Bloom project, which has the potential to grow to a $15bn, 410,000 tonnes-a-year operation, is being backed by Sanguine Impact Investment, which has committed $1bn for the project’s early stages, and to bankroll it in its entirety over time.

Aqua Aerem, the company behind the Tennant Creek-based Desert Bloom project, hopes to start production next year, targeting hydrogen production costs of less than $US2 per kilogram by 2027. The solar power-driven operation would include about 4000 modular, 2MW “hydrogen production units” at its peak.

And there are even plans to drill for naturally occurring, and therefore “gold”, hydrogen.

Brisbane company Gold Hydrogen said in November that it had trawled through the archives, and discovered that two oil wells drilled on the southern part of SA’s Yorke Peninsula and Kangaroo Island had struck hydrogen at up to 80 per cent purity.

Not surprisingly, the company’s director, Neil McDonald, says a resource of gold hydrogen would be “nirvana” as far as producing energy without the associated emissions problems, and his company is not the only one kicking the tyres on the idea of subterranean hydrogen reserves.

The most recent report from energy consultancy EnergyQuest indicates the interest is widespread, calling it a boom, “which began with the chance rediscovery of historical reports of hydrogen results from two wells drilled in the 1930s’’. It says: “From a starting point of zero activity in February 2021, SA now has 18 petroleum exploration licences (granted or applied for) from six companies targeting natural hydrogen. The combined area under permit is 570,000sq km or 32 per cent of the entire state.’’

From a use point of view, there is a trial under way in SA, which has been blending up to 5 per cent renewable hydrogen into the gas supply to about 700 homes.

S&P Global Platts’ New York-based head of future energy analytics, Roman Kramarchuk, said its research shows that last year there was a 580 per cent increase in the commitments to low-carbon hydrogen projects globally, measured by production capacity. And while European jurisdictions were ahead of the game because of the more established carbon trading market, Australia’s projects were remarkable for their size.

“If we look at where the investments going into next year, two or three years, it’s a European story,’’ Kramarchuk says. “Certainly with carbon prices in the €75 ($118)-plus range that makes a difference.’’

Kramarchuk says the prices being calculated for hydrogen in the European market are very high at the moment due to the “crazy’’ gas price levels. But longer term the building blocks of the hydrogen economy are being put in place.

“There’s also a UK hydrogen strategy where they’re right now going through a consultation to figure out what is the best support mechanism,’’ Kramarchuk says. “It’s not whether there’s going to be a support mechanism, it’s what is the best structure?

“It’s going to get into the very specifics of ‘We know we want to support it. Let’s figure out the best structure through which we can support it’.

“People are banking on that because otherwise clean hydrogen is a really hard sell in most parts of the world because there isn’t a carbon price high enough and there isn’t a support structure high enough.’’

One of the aces up Australia’s sleeve was the abundance of renewable energy on offer.

“If you have low demand and you have renewables that lead to curtailments you get negative prices and that’s fantastic for hydrogen,” Kramarchuk says.

Kramarchuk says while there were pushes to develop blue hydrogen in countries such as The Netherlands and UK, the rest of Europe was leaning towards electrolyser-based production.

And in terms of who would be the major players in the future, the incumbent energy companies in Australia, which already have large facility and pipeline management experience, were positioning themselves.

“They see themselves as energy companies, not necessarily natural gas companies,’’ he says.

Platts’ figures show the cumulative capacity in the clean hydrogen project pipeline to be sitting at about 25 million tonnes a year, as at November last year, up from less than five a year ago.

Back in Australia, a report written for the government by KPMG – and released last month – paints a mixed, but positive picture. Investment in the sector, with $1.6bn in committed by private sector, is characterised as “advancing quickly’’, with public sector investment sitting at $1.27bn by June last year. Project announcements to date indicate that the scale could top 100MW by 2025 and “Gigawatt-scale projects have been announced and are expected to start operating in the second half of the decade. However, a final investment decision on these projects has not been made.’’

Advancements in areas such as using hydrogen in steelmaking, and whether it has a role to play in frequency support for the electricity grid, were moving slowly.

“As is to be anticipated as a new industry develops, progress has been slower on demand-side indicators,’’ the report says.

“This is expected given the early state of the industry and the higher cost of clean hydrogen compared to chemicals and fuels currently being used.’

“Many of hydrogen’s expected future uses … have only recently begun trials. Like any new industry, it will take some time to build export supply chains and deliver activities to help scale up the industry.

“Progress is expected to be slow at first, but will increase as costs decrease and markets increasingly adopt new technologies.’’

The report even makes the claim that by mid 2021, “Australia had the world’s largest pipeline of announced hydrogen projects’’.

“If all these projects are completed, Australia could be one of the world’s largest hydrogen producers by 2030,’’ it says.

Technical issues

It won’t be easy though, and there are significant technical and economic issues to surmount.

Hydrogen has a tendency to explode, and must be handled with care. And putting it directly into existing pipelines is not a straightforward option, with problems such as hydrogen embrittlement, which attacks the integrity of steel, a major impediment.

And the cost is also an issue, with some in the industry already ceding areas such as light vehicle transport to an electric-only option, rather than seeing it as a sector to focus on.

Then there is the cost – unless it can viably get to a point where it competes with other renewables, it will be out of the game.

But KPMG reckons Australia is on a winner there. “In 2025 the cost of producing clean hydrogen in Australia is expected to be between $2.30 and $5 per kilogram, depending on the production method,’’ its report says.

“In 2030 it will cost an estimated $2-$4 per kilogram. These are some of the cheapest estimates in the world.’’

Bringing hydrogen below $2 a kilogram – the nation’s stretch goal – will need cheaper and more abundant clean energy, as well as significant development of technologies such as electrolysers.

But with mavericks such as Andrew Forrest on the case, you would have to back Australia in with a chance.

More Coverage

Originally published as Australia pumps up its push to establish a hydrogen industry