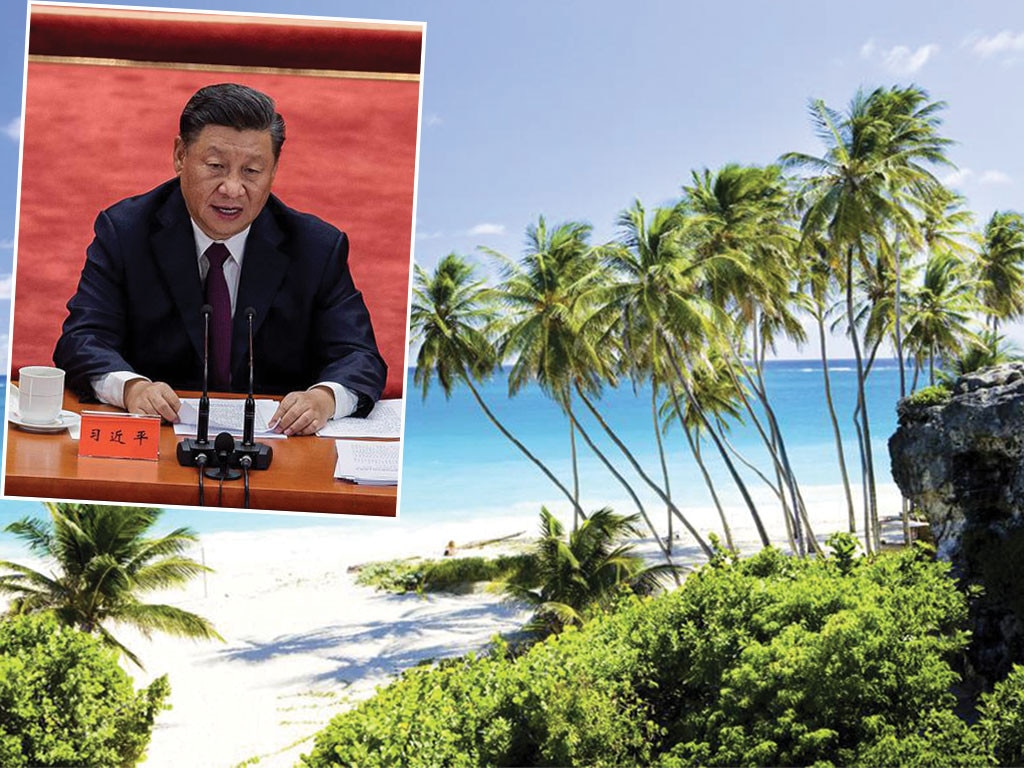

Xi’s dictatorship can’t be trusted

When I was governor of Hong Kong, one of my noisiest critics was Sir Percy Cradock, a former British ambassador to China. Cradock always argued that China would never break its solemn promises, memorialised in a treaty lodged at the UN, to guarantee Hong Kong’s high degree of autonomy and way of life for 50 years after the return of the city from British to Chinese sovereignty in 1997.

Cradock once memorably said that although China’s leaders may be “thuggish dictators”, they were “men of their word” and could be “trusted to do what they promise”. Nowadays, we have overwhelming evidence of the truth of the first half of that observation.

Chinese President Xi Jinping’s dictatorship is certainly thuggish. Consider its policies in Xinjiang. Many international lawyers argue that the incarceration of over one million Muslim Uighurs, forced sterilisation and abortion, and slave labour meet the UN definition of genocide. This wicked repression goes beyond thuggery.

A recent Australian Strategic Policy Institute study based on satellite images indicates that China has built 380 internment camps in Xinjiang, including 14 still under construction. Having initially denied that these camps even existed, some Chinese officials now claim that most people detained in them have already been returned to their own communities. Clearly, this is far from the truth.

So, what about Xi and his apparatchiks being “men of their word”? Alas, that part of Cradock’s description has no basis in reality. The last thing the world should do is trust the Communist Party of China. Four examples of the Chinese leadership’s duplicity and mendacity – four out of many – should make this obvious to all.

First, consider the China-sourced COVID-19 pandemic, which has killed one million people globally and destroyed jobs and livelihoods on a horrendous scale in recent months. After the 2002-03 SARS epidemic, which also originated in China, the World Health Organisation negotiated with its members — including China — to establish a set of guidelines known as the International Health Regulations. Under these rules, especially Article 6, the Chinese government is obliged — like all other signatories to the agreement — to collect information on any new public-health emergency and report it to the WHO within 24 hours.

Instead, as the University of Ottawa professor Errol Patrick Mendes, a distinguished international human-rights lawyer, has pointed out, China “suppressed, falsified, and obfuscated data and repressed advance warnings about the contagion as early as December” last year.

The result is that the coronavirus has become a far greater menace than it otherwise would have been. This is the CPC’s coronavirus, not least because the party silenced brave Chinese doctors when they tried to blow the whistle on what was happening.

Former US president Barack Obama also can attest to Xi’s lack of trustworthiness. In September 2015, Xi assured Obama that China was not pursuing militarisation in and around the Spratly Islands in the South China Sea.

But this was a pledge with Chinese communist characteristics: it was completely untrue. Satellite imagery released by the Centre for Strategic and International Studies, a US think tank, provides convincing evidence that the Chinese military has deployed large batteries of anti-aircraft guns on the islands. At the same time, the Chinese navy has rammed and sunk Vietnamese fishing vessels in these waters and tested new anti-aircraft carrier missiles there.

A third example of the CPC’s dishonesty is its full-frontal assault on Hong Kong’s autonomy, freedom, and rule of law. Hong Kong represents all those aspects of an open society that Chinese communists, despite their professed confidence in their own technological totalitarianism, regard as an existential threat to the surveillance state they have created.

Xi has therefore torn up the promises that China made to Hong Kong and the international community in the 1984 Joint Declaration (and subsequently) that the city would continue to enjoy its liberties until 2047.

Moreover, the law that China imposed to eviscerate Hong Kong’s freedom has extra-territorial scope. Article 38 of the National Security Law can apply to anyone in Hong Kong, mainland China, or any other country. So, for example, an American, British, or Japanese journalist who wrote anything in his or her own country criticising the Chinese government’s policy in Tibet or Hong Kong could be arrested if he or she were to set foot in Hong Kong or China.

Finally, one can add China’s sackful of broken trade and investment promises, which overturned both the letter and spirit of what CPC officials had previously pledged. China’s coercive commercial diplomacy includes threats not to buy exports of countries whose governments have the courage to stand up to Xi. This has happened to Australia, Norway, South Korea, Japan, Germany, Britain, France, Canada, the US, and others. The end result is often less than China had threatened, but not before an industry or economic sector has begged its government to back down.

One thing is clear: the world cannot trust Xi’s dictatorship. The sooner we recognise this and act together, the sooner the Beijing bullies will have to behave better. The world will be safer and more prosperous for it.

Chris Patten — a minister in the Thatcher government, the last British governor of Hong Kong and a former EU commissioner for external affairs — is Chancellor of the University of Oxford.

Project Syndicate