His death presents today’s prime minister, James Marape, with a monumental test. For the politics of funerals — among village clans or within the ship of state — are notoriously demanding in PNG, as interest groups vie for control of ceremonies, for hosting the remains. But the strong Somare family should carry the capacity to have the final say.

I first encountered “the Chief” when, working with Wantok, the Pidgin newspaper, I began attending his remarkably frequent press conferences held in the “Pineapple Building” in Waigani, PNG’s Canberra, immediately after independence.

Somare had been a broadcaster himself, and understood the species pretty well — and would be gracious with young and sometimes nervous reporters.

These were civilised and non-combative gatherings involving a quorum of the nation’s journalists. They were set in a PNG in which citizens and leaders were for a brief, sunny period linked in the common cause of “development,” having achieved independence unexpectedly swiftly and smoothly.

The Chief loved a party. I was there one evening at the old PM’s official house in Boroko when he farewelled rousingly, the great Australian journalist Gus Smales, acknowledging his generosity of spirit in turning his back on a whites-only Highlands club that refused to serve Somare during an early pre-independence political tour. The two instead sat outside, sharing roll-up smokes.

Somare’s personal qualities has enabled him, over a remarkably short period, to draw in other remarkable personalities and leaders during the creation of the Pangu Party, and to build a sense of confidence and optimism that yes, PNG could and would run its own affairs — and swiftly. For a period in mid-career, Somare disappointed PNG, as its high hopes at independence began to be dashed — while he was in turn himself disappointed a little by his own nation, especially by the unstoppable surge into cities by young Papua New Guineans away from village-based “subsistence affluence” on their ancestral lands.

A decade ago, after a press conference during the painful last days of his third prime ministership, Somare, still obviously recovering with difficulty, and no small courage, from major medical treatment in Singapore, was being quietly ushered away.

Apart from his own watchful family members, there seemed no one around from the old days. He glanced around, and spotted me, sitting at the back of the room, as someone who had also known those times of brimming confidence and optimism.

He declined to leave as requested, came over, sat down with a suddenly more relaxed expression — “the old Chief” — and invited me to join in recalling those genuinely good times, and tales of incorrigible political rivals. We talked for a while, then ruefully he regretted that he had to go. That was the last time I met him; an elegiac but warm memory.

Somare, and the nation he embodied, journeyed a long way together. The route was rarely predictable, nor did it reach a destination he would have sought when he chose a political life 54 years ago. But he gave it his best shot, and will today be deeply mourned especially for the great gift of hope that he bequeathed his nation.

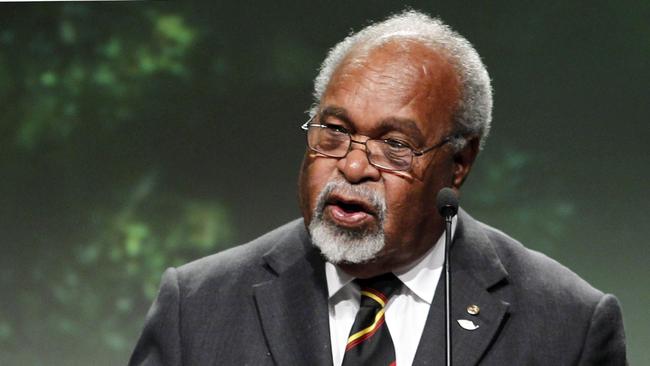

Michael Somare was one of those people who naturally capture the attention of everyone in a room. A stocky figure with a commanding, husky voice, he was charismatic, likeable, loved a joke or an anecdote, and also — an added special Sepik flavour — at times feisty and peppery. He knew himself, a rare quality. He was naturally inclined towards inclusiveness. And he knew that for many at home and abroad, he stood personally, for his beautiful and beloved country.