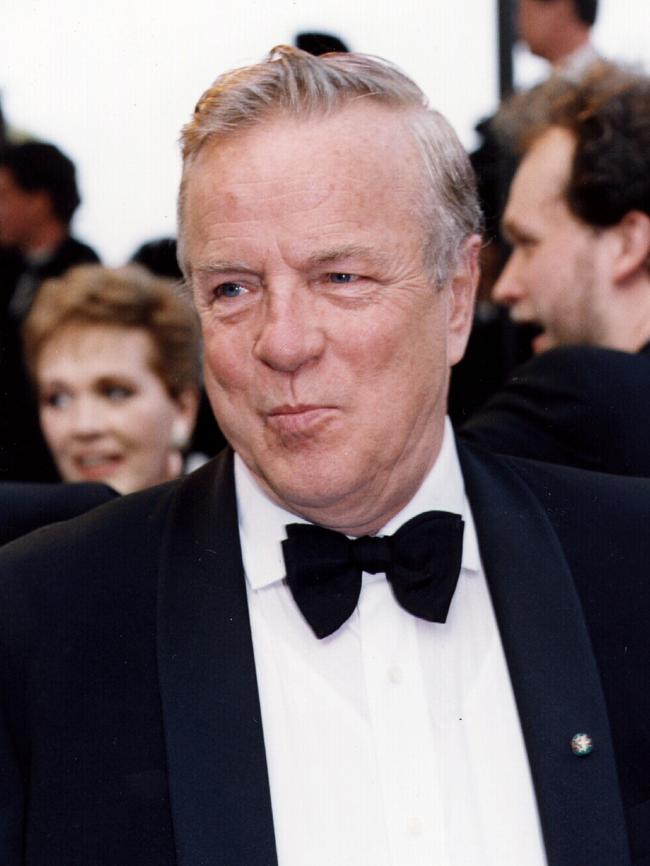

Zeffirelli a master of grand beauty

The life of Italian film director Franco Zeffirelli, it was often noted, would have made a good opera.

Franco Zeffirelli: Film, theatre and opera director.

Born Florence, February 12, 1923. Died Rome, June 15, aged 96.

-

Franco Zeffirelli’s life, it was often noted, would have made a good opera. Not perhaps a tragedy, although as an illegitimate orphan he had a hard start, but certainly something Italian. That is to say, something that played to his forte, which was for beauty in design and, at his peak, for communicating grand emotion with all the open-heartedness of a child.

Almost uniquely, he made superlative contributions not only to opera, notably with a Tosca in London in 1964, but also to the theatre and to film. His version of Romeo and Juliet arguably has yet to be surpassed. A decade later, his drama series Jesus of Nazareth was one of the great television events of the period.

“It’s like being a sultan with three wives,” said the versatile Zeffirelli, who gave quotations to interviewers with all the zest of a hornet in the stables. “When you’re having sex, you think: ‘Next time I have to try the other one.’ ”

Faithlessness of this kind was not his only flaw. His shrieking rages were the stuff of show-business legend and his brisk dismissals of lesser talents legion. Undoubtedly, he brought pleasure to millions, even if the suspicion was always that he regarded his finest work as himself.

Gian Franco Zeffirelli was born in Florence in 1923. His mother kept a dress shop, while his father was a wool merchant. They were married, but not to each other. Alaide Garosi had three other children by her husband, a lawyer suffering from tuberculosis, and at his funeral was pregnant with Franco. When the boy first went to school, he was followed through the streets by his father’s wife, screaming after him “Bastardino!”

Ottorino Corsi did not acknowledge his son until he was 19. Franco’s mother wanted to give him the surname Zeffiretti, but the register clerk misheard what was said, fixing him as Zeffirelli. In recent years he learned that through his father he was one of the few remaining descendants of Leonardo da Vinci’s family.

When he was six, Franco’s mother died and afterwards he was raised by his father’s cousin (whose lover introduced him to opera) as well as by a young cook cum nanny, Edvige, who continued to live with him until he and she were in their 90s.

He was taught an idiomatic English by Mary O’Neill, an expatriate who translated his father’s business letters, and spent much time with the other ladies of Florence’s English community. His relations with them, and their fate during World War II, was the inspiration for his film Tea with Mussolini (1999), featuring Judi Dench, Maggie Smith and Cher.

Franco was sent to a convent school, where a friar introduced him to sex. He would have heterosexual relationships as a teenager (he lost his virginity to his girlfriend’s mother), but came out publicly as homosexual only late in life. He disliked the term gay, finding it insufficiently virile.

He trained as an architect, but after watching Laurence Olivier’s film of Henry V he decided to make his life in the theatre. He began as a scenery painter, but in 1947 he was introduced to director Luchino Visconti. Beginning as art director for Visconti, he would become an assistant director on films of his such as La terra trema and Senso. He and Visconti also lived together in Rome. Their relationship ended abruptly after Zeffirelli was arrested by police investigating a burglary at Visconti’s villa.

By the early 1950s Zeffirelli was directing for the stage and by the end of the decade was also making his name in opera. His first great success came in Dallas in 1958 with La Traviata sung by Maria Callas. In 1959 at the Royal Opera House he staged the Lucia di Lammermoor that forged Joan Sutherland’s reputation. Further triumphs soon followed at La Scala, at La Fenice and in Vienna, where his production of La Boheme would be staged 400 times during the next 50 years.

The apex of this success was reached in London in 1964 when Callas appeared in Tosca. Zeffirelli spared no expense and contrived a vision that was highly engaging, showing how he had reinvigorated opera as an art form. Part of the production’s appeal, as Zeffirelli was aware, was his star’s relationship with Aristotle Onassis. As the police chief Scarpia, Tito Gobbi played a version of the shipowner, attracting and repelling the heroine. Callas took 27 curtain calls.

His 1960 production of Romeo and Juliet rendered the play vital rather than merely romantic. He cast little-known actors (including Judi Dench), capturing the sense of the original and the spirit of the 60s. Although some hated it, critic Kenneth Tynan called it “a revelation, perhaps a revolution”. He filmed it in 1968, having in the meantime shot The Taming of the Shrew with Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor (dumping plans to make it with Sophia Loren and Marcello Mastroianni when the screen’s biggest stars told him they had loved his Romeo.)

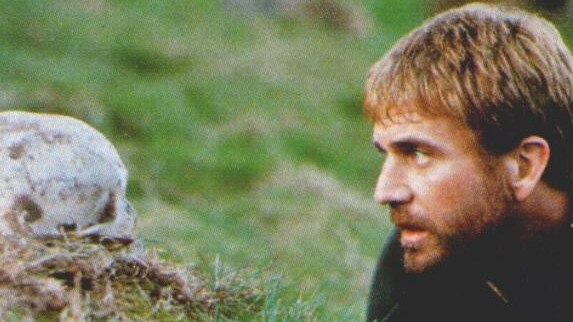

In the mid-80s he concentrated on filming operatic productions for the new video market, Placido Domingo featuring in fine renditions of La Traviata and Otello. Mel Gibson was a bold choice for his Hamlet in 1990, a gamble that largely paid off, although Jane Eyre (1996) was generally thought self-defeatingly lacking in sparkle.

By then, he had found a new amusement: politics. His friendship with Silvio Berlusconi, who had paid for his villa on the Appian Way in Rome, led to his election in 1994 as a senator for the tycoon’s Forza Italia party.

Besides cigarettes, his principal indulgence was his dogs, mainly Jack Russells and strays he had found in Romania, which he fed on a diet of mozzarella.

When younger, he had kept a holiday home at Positano, to which he invited celebrities such as Liza Minnelli and Gregory Peck. He liked to claim that Burton and Taylor had their first kiss in his swimming pool. He had no long-term companion or children, although he adopted two former lovers, Pippo and Luciano, who looked after his business affairs and managed his household.

“Certainly the idea of death is frightening,” he told The Times in 2011. “But for me, a human being is a masterpiece. That clearly shows there is some divinity coming to help us make men better. Death is just the beginning.”

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout