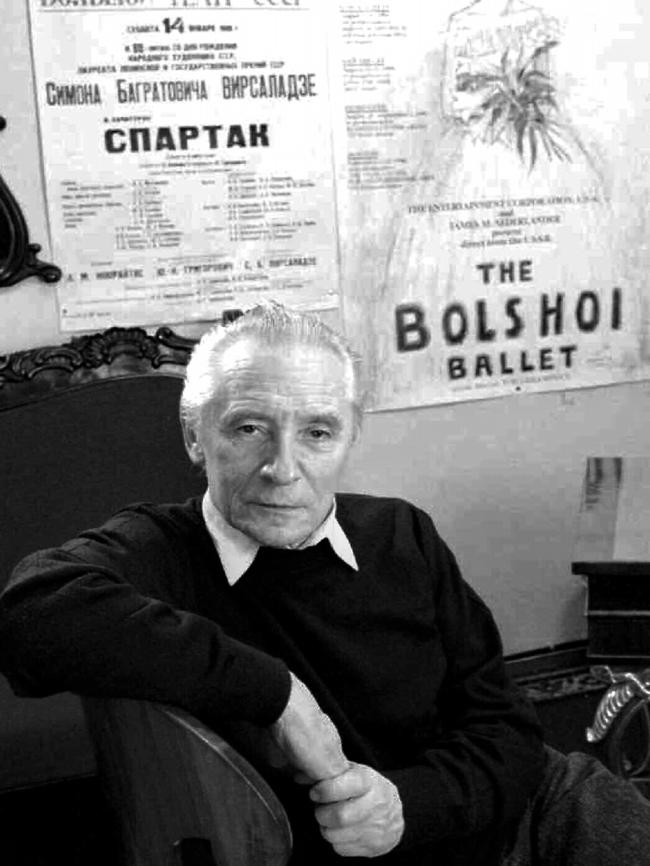

Yuri Grigorovich was one of the 20th century’s greatest choreographers

The Master of the Bolshoi Ballet, Yuri Grigorovich, was accused of being a tyrant but also described as one of the great choreographers of the 20th century.

From The Red Shoes to Black Swan, the image of the angry, uncompromising ballet master has been well mined in film but never more frighteningly embodied in reality than by Yuri Grigorovich.

Dwarfed by the tall and athletic dancers favoured by the pantheon of the art form in Russia, the 152.5cm former dancer was, at times, a tyrannical leader of the Bolshoi Ballet from 1964 to 1995.

And though with no false modesty he declared in his autobiography that “Yuri Grigorovich is considered to be the greatest living choreographer in the world of ballet”, it was a view shared by many connoisseurs on both sides of the Iron Curtain.

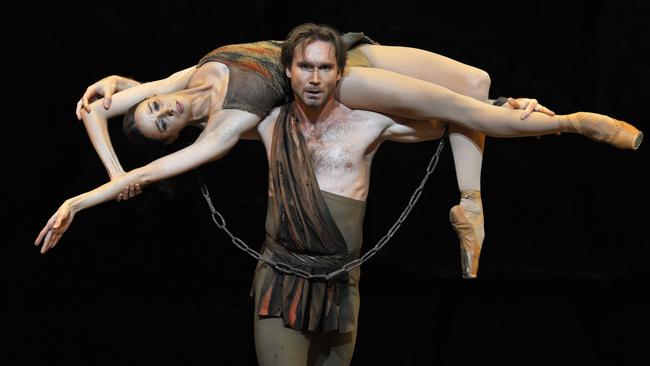

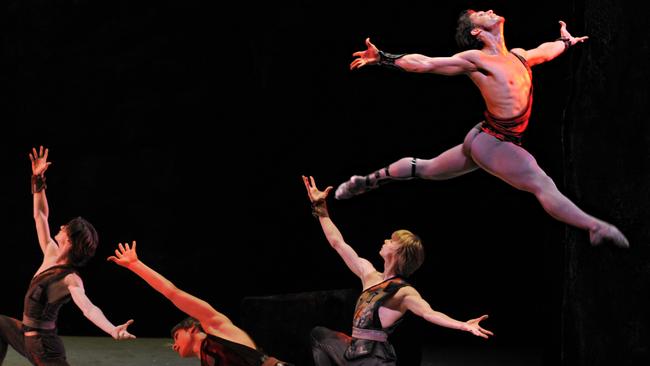

Grigorovich’s magnum opus as a choreographer wasSpartacus, in which Aram Khachaturian’s colossal, pounding music is allied to thrilling movement.

Exemplifying the powerful, athletic, expansive and heroic style of his ballets, that was in keeping with the sensibilities of Soviet communism and a strident evangeliser of its values, the ballet was the perfect vehicle for his principal dancer, Vladimir Vasiliev, to demonstrate his virtuosity with arguably the most demanding male role ever created. The ballet became a worldwide hit after it premiered in 1968.

Grigorovich had emerged when classical ballet was still being undermined by socialist realist orthodoxies and the Soviet drambalet, a form favouring drama over balletic artifice. Grigorovich, however, prioritised the classical language in such a way that evaded the censor’s eyes.

Along with another Leningrad choreographer, Igor Belsky, he launched a new era of what Soviets called dance symphonism, asserting the primacy of musical interpretation through allusive dance and reinventing ballet as a contemporary form.

This aesthetic was in keeping with his native city, where classical traditions, ingrained from the time when Leningrad was the imperial family’s home, could be more easily preserved away from the gaze of Moscow.

By the end of the 1960s he had cemented his reputation as the single most influential figure in Russian dance. Yet just as the once all-powerful Kremlin was now beginning to falter, so Grigorovich’s iron grip on the Bolshoi began to loosen by the late 70s.

Vasiliev, whom many consider to be an even greater dancer than Rudolf Nureyev, led the rebellion along with Ekaterina Maximova, Maris Liepa and Maya Plisetskaya, who were openly critical of Grigorovich’s increasingly autocratic approach, his monopoly of the repertoire and what many considered to be his clunky monumentalist style of choreography.

Criticism from the West, once dismissed in Moscow as capitalist propaganda, now was being taken more seriously.

Plisetskaya, who had shunned opportunities to defect to the West because of her love and loyalty for the Bolshoi – which she called “the greatest stage there is” – harboured particular animus towards him. She accused Grigorovich of favouring his wife, Natalia Bessmertnova, with the best roles.

Even though Plisetskaya was over 40, she was still the darling of the ballet-loving public in Moscow. She was not easily cowed by Grigorovich’s volcanic temper, building up her own faction of dancers in the company. A thinly veiled reference to Grigorovich in her autobiography says: “Our servile, and later semi-servile life, gave rise to many a little Stalin. The mortar of Soviet society was fear … And there were plenty of reasons for fear at the Bolshoi.”

After years of mounting intrigue behind the cloth curtain of the Bolshoi, Grigorovich was sacked in 1995 and succeeded by Vasiliev. But for all the histrionics, Grigorovich had plenty of loyal company members in his camp, who staged a strike in sympathy.

Grigorovich was born in Leningrad in 1927, the son of Nikolai Grigorovich, an accountant, and Klaudia (nee Rozai). Young Grigorovich entered Leningrad’s famous Vaganova academy. He made his debut on the Kirov (now Mariinsky) stage aged 10 in The Nutcracker.

Graduating into the Kirov Ballet in 1946, he featured in character roles, among them Nurali in The Fountain of Bakhchisarai. Because of his short and relatively stocky stature, he would never be considered for leading roles but excelled as a “grotesque dancer”, performing quirkier, comic roles that required explosive movement and contortion of the body.

In 1948, aged 20, he choreographed his first ballet, The Baby Stork, for 120 children at the Maxim Gorky Palace of Culture in Novosibirsk. It brought Grigorovich to the attention of the eminent choreographer Fedor Lopukhov, whose early dance symphonism (then pejoratively labelled as formalism) was a key influence.

In 1957 Grigorovich made his choreographic debut with the Kirov Ballet: The Stone Flower used fairytales from the Urals and a score by Prokofiev. The ballet already had been premiered three years earlier in an inferior staging by Leonid Lavrovsky for Moscow’s Bolshoi. Grigorovich’s version, by contrast, was a big success and transferred to the Bolshoi stage in 1962 with Plisetskaya heading the cast.

Grigorovich’s next creation, The Legend of Love (1961), based on an epic eastern fable, was another Kirov success, acquired by the Bolshoi in 1965. Like The Stone Flower it represented a new direction in which ballet was a metaphorical language, unfolding like symphonic music and using the corps de ballet as a lyrical accompaniment to the soloists.

Under Lopukhov’s guidance Grigorovich evolved a genre in which everything – the action, the emotions – was danced, dissolving the conventional separation of narrative gesture and dance. So where, for example, Prokofiev had visualised the market scene in The Stone Flower as a real-life setting for danced entertainments, in Grigorovich’s ballet it became a market depicted in dance.

When Nureyev defected to the West in 1961, punishment was meted out to senior figures at the Kirov. Grigorovich benefited, appointed chief ballet master in 1963.

A year later he replaced Lavrovsky as artistic director of the Bolshoi.

The high watermark was Spartacus, allying a largely classical language to the narrative’s immaculate socialist credentials whereby the slave Spartacus leads a rebellion against Roman oppression. The result was created in a painstaking collaborative process with the lead dancers – Vasiliev and his wife Maximova, Liepa and Nina Timofeyeva. It also showed Grigorovich to be a master of exciting athletic display, a peerless creator of searingly dramatic characters whose explosive solos matched the larger-than-life idealisations of socialist realism.

Everything was articulated through the powerful contrast of the two male characters, Spartacus (the glamorously virile Vasiliev) and his evil Roman opponent Crassus (the equally charismatic and virtuosic Liepa), and was danced with “an almost suicidal bravado”, according to The Times’ review of the 1969 London premiere. Spartacus, above all, rehabilitated the classical language as a contemporary idiom for Soviet ballet. Abroad, it became the Bolshoi’s calling card, introducing new generations of Bolshoi stars, such as Irek Mukhamedov.

The same year as Spartacus premiered, Grigorovich married Bessmertnova. He had divorced his first wife, Kirov ballerina Alla Shelest. Bessmertnova died in 2008. Never a believer in the value of diplomacy, Grigorovich once said: “I married my first wife for her intelligence, and my second for her beauty.”

Grigorovich choreographed Ivan the Terrible to Prokofiev’s music for Sergei Eisenstein’s film in 1976 and restaged it at the Paris Opera a year later. This was followed by Angara (1976), named after the Siberian river and based on a play by Aleksei Arbuzov. Its themes of contemporary youth and the relations between the individual and the collective were supplemented by the choreographic image of the Angara, created by the corps de ballet, which travelled through the ballet as a leitmotiv.

More often, though, Grigorovich re-choreographed ballets, such as Romeo and Juliet to the familiar Prokofiev score. In 1982 he turned to Shostakovich’s score for The Golden Age, another previously unsuccessful ballet. Again, he proved that a symphonic ballet structure could be applied to a modern setting – here, young workers confronted gangsters and seedy bourgeois individuals. It was one of his more successful ballets in London, but it was to be his last original choreography.

Thereafter he would focus on the classics, such as The Nutcracker and Sleeping Beauty, to which he would apply his own distinctive visions. Yet his 1969 Swan Lake, scheduled for the same London season as Spartacus, had a troubled genesis. Grigorovich was forced to make hurried changes by culture minister Yekaterina Furtseva and replace the tragic finale with the standard Soviet “happy ending”. It was only with his second version in 2001 that he could fulfil his initial intention and present Siegfried as the victim of an inevitable tragic fate and Odette as an unattainable ideal.

He received the Lenin Prize (1976 and 1986); and the Order for Merit to the Fatherland (First Class), the second highest order of the Russian Federation (2011). By then Grigorovich had returned to centre stage. Some said it was no coincidence that as Russia regressed to authoritarianism politically, Grigorovich returned as staff ballet master of the Bolshoi in 2008 at the age of 81, as uncompromising as ever.

Yuri Grigorovich. Ballet master of the Bolshoi. Born Leningrad, Soviet Union, (now St Petersburg, Russia) January 2, 1927; died May 19, 2025, aged 98.

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout